Source: Quantum Number

In today's society, "creativity" has become an almost unquestionable universal value. From classroom education to corporate strategy, from personal development to urban planning, "creativity" seems to be everywhere. We praise it, pursue it, measure it, commercialize it, and even build a whole ideological system around it. But is creativity really an unchanging human talent? Does its rise have other historical roots and cultural motivations?

In the book "The Cult of Creativity: The Rise of a Modern Ideology", historian Samuel Franklin systematically sorted out the development of the concept of "creativity" from scratch, revealing how it evolved from a cultural stress response to institutionalized anxiety in the United States in the mid-20th century to a core belief that is almost unquestionable today. He traced how psychologists tried to quantify creativity, how governments and companies institutionalized it, and how the technology industry used it to shape its own image. At the same time, he also pointed out that behind this fanatical admiration for creativity, there are structural problems of inequality, anxiety and illusory promises.

Recently, MIT Technology Review interviewed Samuel Franklin. In this article, he gave us the opportunity to think deeply about a seemingly simple but controversial question: Why are we so obsessed with "creativity"? As artificial intelligence is increasingly approaching the boundaries of traditional human capabilities, how should we re-understand this trait that was once considered unique to humans? This is an intellectual journey about the evolution of ideas, and it is also a deep interrogation of the value system of modern society. Please continue reading.

Today, people find it difficult to reach a consensus on many things. However, even in an era when consensus reality is almost collapsing, there is still a modern value that almost everyone agrees on, that is: creativity.

We educate about creativity, measure it, admire it, foster it, and endlessly worry about its demise. And no wonder. From childhood, we are taught that creativity is the key to personal fulfillment, professional success, and even solving the world's most intractable problems. Over the years, we have established "creative industries", "creative spaces" and "creative cities", and have named an entire class of people who work in them as "creative people". We read countless books and articles every year to learn how to unleash, inspire, cultivate, enhance, and even "hack" our own personal creativity. Then we read more to learn how to manage and protect this precious resource.

Amid this enthusiasm, the concept of creativity seems like a kind of common sense that has always existed in human civilization, a proposition that philosophers and artists have been pondering and debating for ages. This assumption seems reasonable, but it is actually wrong. As Samuel Franklin points out in his new book, The Cult of Creativity, the first written use of the word “creativity” is in 1875, and “as a word, it is still a baby.” More surprisingly, he writes that before 1950, “it is virtually impossible to find any article, book, essay, thesis, ode, course, encyclopedia entry, or anything else that deals exclusively with the subject of ‘creativity.’”

This raises a number of obvious questions: How did we go from almost never talking about creativity to talking about it all the time? And how exactly is “creativity” different from older words like “ingenuity,” “cleverness,” “imagination,” or “artistry”? Perhaps the most crucial question is: Why do kindergarten teachers, mayors, CEOs, designers, engineers, activists, and even starving artists all believe that creativity is not only a virtue—personally, socially, and economically—but also the answer to all of life’s problems?

Thankfully, Franklin offers some possible answers. A historian and design researcher at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, he notes that creativity as we know it today emerged in the cultural context of post-World War II America as a kind of psychotherapy to relieve the tensions and anxieties of growing conformism, bureaucracy, and suburbanization.

"Creativity is often defined as a trait or process vaguely associated with artists and geniuses, but in theory anyone can possess it and it applies to any field," he wrote. "It provides a way for individuals to be liberated in order and to revive the spirit of lonely inventors in the maze of modern enterprises."

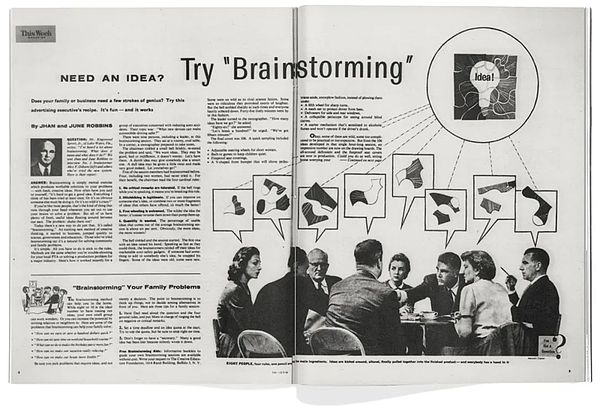

Brainstorming, as a new method to stimulate creative thinking, swept the entire American corporate world in the 1950s. This method not only responded to the demand for new products and new marketing methods, but also reflected people's panic about social homogeneity and sparked a heated debate: Should true creativity be an independent individual behavior, or can it be used by enterprises in a systematic and mechanism-based manner? (Photo credit: UC Berkeley Institute for Personality and Social Research/Monacelli Press)

MIT Technology Review spoke with Franklin about why we remain so fascinated by creativity, how Silicon Valley became the so-called “center of creativity,” and what role technologies like artificial intelligence might play in reshaping our relationship with creativity.

I’m curious about your relationship to creativity as a child, and what made you want to write a book about it?

Like many children, I grew up believing that creativity was an innate virtue. For me—and I imagine for many people like me who weren’t great at sports, math, or science—being creative meant that you had at least some kind of purpose in the world, even if it was still unclear what that purpose was. By the time I got to college, TED-style thought leaders—people like Daniel Pink and Richard Florida—had enshrined creativity as the most important quality of the future. Basically, the future belonged to creative people, and they were needed if society was to solve its myriad problems.

On the one hand, as someone who likes to think of myself as somewhat creative, it was hard not to be drawn to and moved by this narrative. But on the other hand, I also felt that the narrative was grossly overstated. The so-called “triumph of the creative class” had not really led to a more inclusive or creative world order. And some of the values implicit in what I call the “cult of creativity” began to look increasingly problematic—particularly the overemphasis on “self-actualization,” “doing what you love,” and “following your passion.” Don’t get me wrong—it was a beautiful vision, and I did see some people benefiting from it, but I also began to feel that, from an economic perspective, it was just masking the difficulties and setbacks that many people were facing.

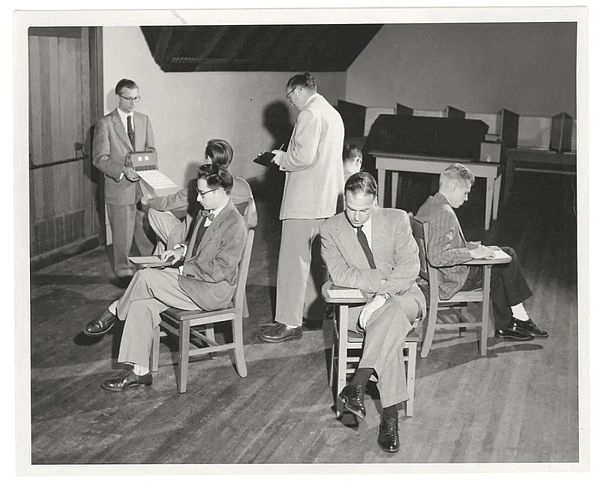

In the 1950s, staff at the University of California, Berkeley, designed a situational interactive experiment called the "Bingo Test" to understand what factors in people's lives and environments affect their creative potential. (Photo source: UC Berkeley Institute for Personality and Social Research/Monacelli Press)

Today, it's commonplace to criticize the culture of "following passion" and "struggling hard." But when I started this research project, the idea of "moving fast, breaking the rules," disruptor thinking, and innovative economy was almost unquestioned. In a way, the idea for the book came from that—I found that creativity was somehow a bridge between two worlds: the world of innovation and entrepreneurship, and the more sentimental, bohemian side of culture. I wanted to understand more about the historical relationship between the two.

When did you first start thinking of creativity as a “cult” phenomenon?

Like the “cult of domesticity,” I was trying to use the term to describe a moment in history when an idea or value system gained widespread and uncritical acceptance. I began to see all kinds of products being marketed as “boosting your creativity”—whether it was new office space designs, new urban planning, or “try these five simple techniques” and the like.

You start to realize that no one is stopping to ask, "Hey, why do we all have to be creative? What is creativity?" It's become this unquestionable value that no one would think to question, regardless of one's political affiliation. To me, that's very unusual and a sign that something very interesting is going on.

Your book focuses on the attempts by psychologists in the middle of the last century to turn "creativity" into a quantifiable psychological trait and to define the "creative personality." How did that effort ultimately pan out?

In short: it didn't work very well. To study anything, you have to have a clear consensus on what you're studying. And ultimately, I think these groups of psychologists got very frustrated with the scientific criteria for defining what a "creative personality" is. One way they did this was to go directly to people who were already famous in fields that were considered creative—writers Truman Capote and Norman Mailer, architects Louis Kahn and Eero Saarinen—and give them a battery of cognitive and psychoanalytic tests and compile the results. Much of this research was conducted by the Institute for Personality Assessment and Research (IPAR) at the University of California, Berkeley, with Frank Baron and Don McKinnon as two of the most important researchers.

Another explanation from the psychologists was, “Well, these case studies aren’t practical for developing a scientific universal standard. What we need is a lot of data, and enough people to verify these ‘creativity standards.’” The psychologists theorized that “divergent thinking” might be a key component of creative achievement. You may have heard of the “brick test”? It’s about coming up with as many uses for a brick as possible within a time limit. They basically gave variations of these tests to all sorts of people - military officers, elementary school students, GE engineers... all kinds of people. Tests like these eventually became the representative means of measuring "creativity."

Are these tests still used today?

When you see those headlines about "AI making humans more creative" or "AI more creative than humans," the test they're relying on is almost always some form of "divergent thinking test." This is problematic on multiple levels, the main one being: these tests have never been proven to be predictive. In other words, a third grader, a 21-year-old college student, or a 35-year-old adult doing well on a divergent thinking test does not mean they will achieve success in a creative field in the future. And these tests are designed to identify and predict "people with creative potential." But so far, no test has actually been able to do that.

The cover of Samuel Franklin's book The Cult of Creativity.

While reading your book, I noticed that "creativity" has been a vague and often contradictory concept from the beginning. In your book, you call this vagueness "a feature, not a bug." Why do you say that?

Today, if you ask any creativity expert what "creativity" means, they will most likely tell you that creativity is the ability to create something new and useful. This thing can be an idea, a product, an academic paper, or even any form of achievement. But in any case, "novelty" is always the core concern of creativity, and it is also one of the fundamental differences between it and other similar words such as "imagination" and "ingenuity". But you are right: creativity itself is a flexible enough concept that can be used in various contexts and mean various different (even contradictory) things. I also mentioned in the book that although the word may not be precise, its ambiguity is precisely accurate and meaningful. It can be playful or practical; it can be artistic or technical; it can be both outstanding and everyday. And this is an important reason for its popularity.

Is the emphasis on "novelty" and "practicality" also one of the reasons why Silicon Valley sees itself as the center of contemporary creativity?

Absolutely. The two standards are not contradictory. In a techno-messianic and hyper-capitalist environment like Silicon Valley, novelty is meaningless without utility (or at least market potential); and utility is equally worthless (or hard to sell) without novelty. As a result, they tend to despise seemingly mundane but extremely important things, such as craftsmanship, infrastructure, system maintenance, and incremental improvement; they support art only because it can inspire practical technology to some extent - and art is often inherently a resistance to practicality.

At the same time, Silicon Valley is also happy to package itself with "creativity" because it carries its own artistic temperament and symbolic meaning of individualism. They deliberately break away from the traditional image of engineers wearing neat uniforms in the R&D labs of physical manufacturing companies, and instead create an image of a counter-culture "garage inventor" - a rebellious character who is outside the system and tinkers with intangible products and experiences in his garage. This image has also helped them to avoid a lot of public doubts and scrutiny.

We have long thought of creativity as a uniquely human trait, with some exceptions in the animal kingdom. Is artificial intelligence changing that?

In fact, as early as the 1950s, when people began to define "creativity", the threat of computers replacing white-collar jobs was already apparent. At that time, the idea was: OK, rational and analytical thinking is no longer exclusive to humans, so what can we do that machines can never do? And "real creativity" was the answer - it was the last bastion of humanity. For a long time, computers did not pose a real challenge to the definition of "creativity". But now it is different: Can they make art and write poetry? Yes. Can they create new, reasonable and useful products? Of course they can.

I think this is intentional in Silicon Valley. Those large language models are intentionally built to fit our traditional definition of "creativity". Of course, whether what they generate is truly "meaningful" or "intelligent" is another question. If we are talking about "art", I personally think that "embodiment" is a very important factor. Nerve endings, hormones, social instincts, moral sense, intellectual honesty - these may not be necessary conditions for creativity, but they are key factors in creating "good works" - even the kind of "beautiful" works with a bit of retro flavor. That's why I say that the question of "Can machines be truly creative?" is not so important; but "Can they be intelligent, honest and caring?" is what we should really think about, especially when we are preparing to incorporate them into our lives and make them our advisors and assistants.

Kikyo

Kikyo

Kikyo

Kikyo Brian

Brian Alex

Alex Kikyo

Kikyo Brian

Brian Alex

Alex Alex

Alex Alex

Alex Joy

Joy Brian

Brian