Author: Sam Hart, Laura Lotti, Toby Shorin; Compiler: Block unicorn

"Dynamics : The Geometry of Behavior, Ralph H. Abraham and Christopher D. Shaw (1992)", embodying the interactions between systems.

The original intention of cryptocurrency is to build institutions that will not decay. However, attempts ranging from DAOs to crypto-states to embed these structures into the broader fabric of society have mostly failed. We draw on the legal theory of Lawrence Lessig to explain why. Protocol designers work with markets and code, but often overlook the crucial institutional functions played by social norms and laws themselves. The lack of these regulatory functions greatly limits the forms of prosocial behavior that can be fostered or enforced.

From stateless currency to cryptostate

2008 The financial crisis ushered in a new era of institutional distrust. The public is forced to face the incredible truth: the monetary system itself no longer serves their interests. The Occupy movement is one expression of public discontent, while others are turning to Bitcoin and betting on an incorruptible currency powered by self-executing software as an alternative to fiat institutions.

However, where we once talked about separating currencies from states, now we hear about cryptostates and constitutions. In crypto, political rhetoric has shifted from avoiding the state to emulating the state, with democratic voting models and public goods as the primary focus. Underpinning this change is a new ideology that crypto is the next “Leviathan,” rivaling states in achieving immutable rights. According to some, blockchain will replace the state's monopoly on violence with a reliable, neutral, decentralized cryptographic infrastructure, allowing the creation of independent property rights and "cyberstates."

Block unicorn annotation: "Leviathan" (English: Leviathan), also translated as "The Theory of Giant Spirits", the full name is "Leviathan, or Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Common Wealth Ecclesiastical and Civil was a work published by Thomas Hobbes in 1651. "Leviathan" was originally a monster recorded in the Old Testament, and is used in this book to describe a powerful country. This book systematically expounds the theory of state and explores the structure of society. Its ideas such as the theory of human nature, social contract theory, and the nature and role of the state have had a profound impact on the Western world. It is one of the famous and influential political philosophy works in the West. 1 (entry source Wikipedia).

As we celebrate experiments in institutional formation through software, in order to rehearse the radical politics of the 18th century, these efforts ignore a core feature of the state: the regulatory power of law. When a Silicon Valley bank fails, the state can act unilaterally to guarantee its deposits. Crypto has no such feature. When the protocol is hacked, everyone loses their money, and only a majority proposal votes for a network fork to restore users' funds.

Censorship-resistant immutability to the law is cryptography’s greatest achievement, but also its greatest weakness. By resisting the all-encompassing influence of the law, it creates a new kind of politics in crypto, a space where power operates according to different rules. However, while stripping away the law,encryption protocols face a three-body problem. 1) Social norms, 2) Markets, 3) Codes each have their own regulatory logics, and they are often found in conflict. On this novel chessboard, protocol designers’ intentions can be undermined, leading to undesirable institutional behavior, ethical dilemmas, and contradictory governance policies.

Interventions that attempt to strengthen the regulatory dimension of norms show potential to address these limitations, but they are often suppressed by the primacy of hard-coded market incentives. Perhaps the answer to strengthening normative self-regulation can be found in the cultural context that already exists.

Regulatory state (social norms)

While software may is devouring the world, but this is a world that has already been devoured by law. Through law, humans become legal persons with rights, "nature" is defined and protected, and law strives to maintain order between sea and land. Law is ubiquitous and plastic, and it is the basic institutional technology of the modern state. Although the nature of law remains the object of scholarly debate, its main feature is clearly the regulation of behavior. The law sets standards of conduct that uphold public values and protect freedoms. Likewise, laws deter or punish harmful behavior by imposing sanctions.

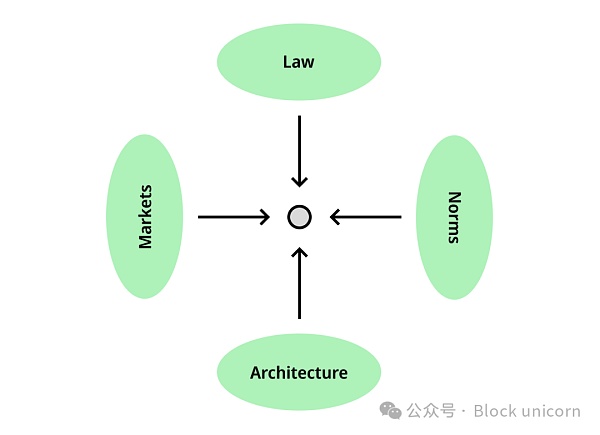

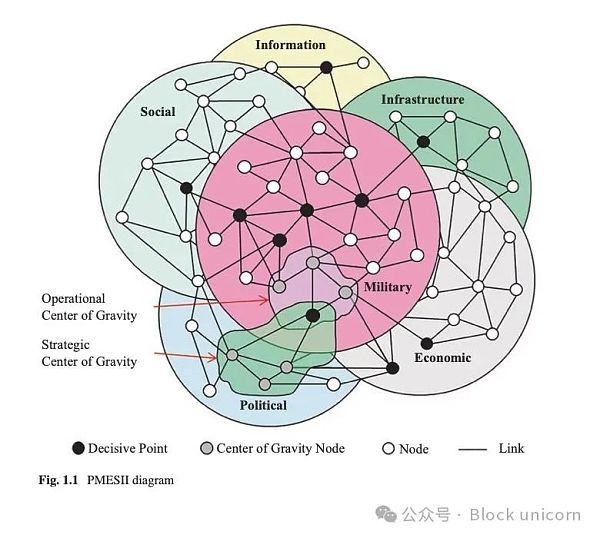

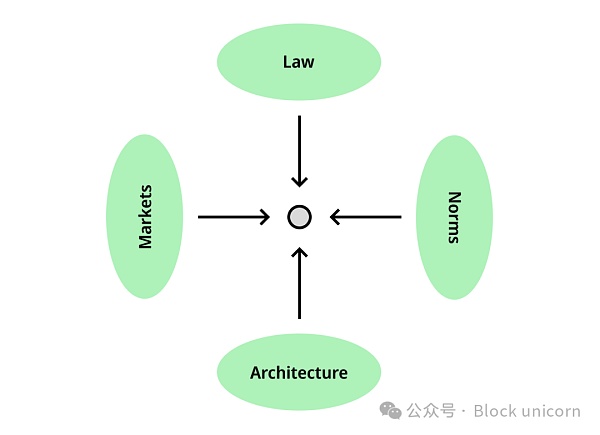

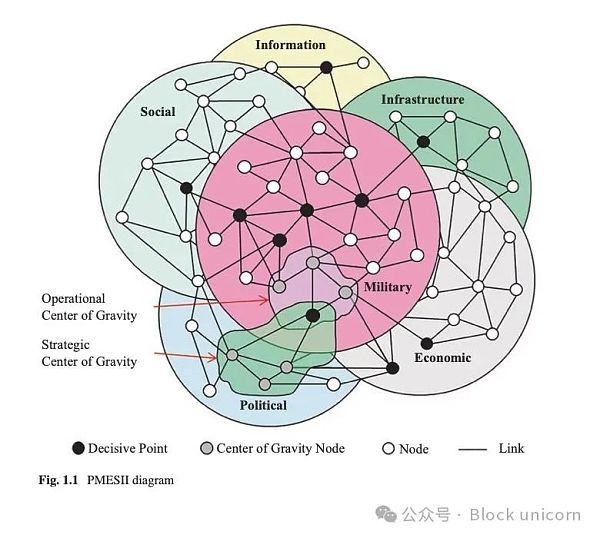

National law is not the only force regulating res publica (public affairs). In his landmark 1998 article, Lawrence Lessig discussed the four forces—law, markets, social norms, and the structure of the built environment—that govern everyday life. 1) Regulations dictate socially acceptable behavior; 2) Markets regulate economic exchanges through the price mechanism; 3) Construction works by defining space and directing the flow of people and information. 4) Finally, the law regulates behavior through institutional prerogatives and enforcement means. Together these forces determine the space of possibilities, taking into account the physical, social and economic circumstances. "We the people" are just the "poor points (poor people)" of these four regulating powers.

For this "poor point", four regulatory patterns that constrain behavior, adapted from Lessig 1998.

Among these four forces, law occupies the highest position in the country. Lessig tried to explain how the law achieves its own regulatory (or regulatory means) goals by influencing other regulatory forces. For example, when Japan imposed high taxes on foreign rice, ensuring that Japanese consumers ate homegrown rice, the law was regulated through the market. We are all familiar with the public health campaigns that have developed around mask-wearing and vaccinations during a global pandemic: this is regulated by law through the establishment of normative policies. As for whether technology forms part of our digital “built environment”, the law also attempts to regulate it.

However, the power to regulate through other forces often becomes the power to regulate everything. Take the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), for example, which makes it illegal to access content that bypasses digital rights management locks, strengthening the gray market for digital piracy. While the DMCA was a controversial and ultimately unsuccessful policy, it revealed the law's tendency to expand. Law tends to expand itself and regulate new technological and social phenomena, even if legislators do not yet fully understand their significance.

The architects of social contract theory, among them Grotius, Locke, and Rousseau, could not have foreseen the penetration of law into every aspect of life. But the dominance of law is inevitable, and law is more than just punishment and restrictions on behavior; it can also empower and provide protection. Through the law, the rights of minority groups can be protected and conflicts between parties can be adjudicated. Although the law does not always pursue an upward curve in the direction of justice, the law still provides a base layer that is perceived as neutral, including a clear path for citizens to update the rules of the game. As Max Weber said, if the state is a human community that successfully maintains a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence, then the rule of law is the tool used by the state to secure a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence. Lessig himself was wary of the influence of his own ideas. :

The regulation of this school is all-round. It is an effort to make culture serve power and a "colonization of the life world." Each space is extensively controlled; controlling the potential of each space is the goal.

But today, the sovereignty of the country is being challenged. Although this process began before the advent of cryptocurrencies, blockchain takes this fight to a whole new level. In fact, the regulatory system composed of states, the Federal Reserve System, and “too big to fail” banks is exactly what cryptocurrencies undermine. However, in order to understand how blockchains can introduce a newregulatory regime, we need to turn to their fundamental innovation: censorship resistance.

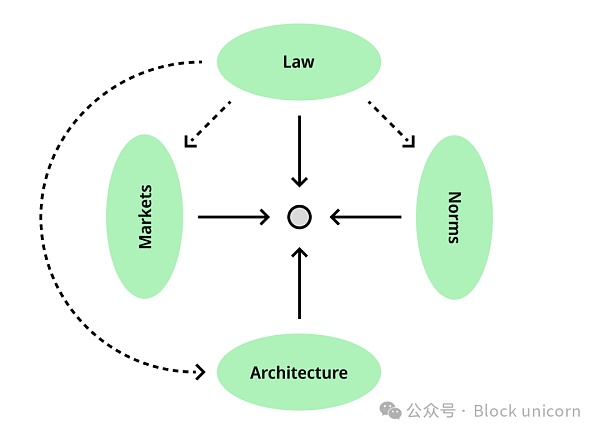

Law works through other forces and is regulated through them.

Censorship resistance equals legal resistance

While the state remains the only legitimate social actor claiming its regulatory authority, a range of competing interests, technologies and economies of scale infringe on the law's alleged sovereignty. International business is increasingly conducted through private dispute resolution centers rather than through international agreements. Meanwhile, global alliances in finance and software challenge state regulation of markets; when Elizabeth Truss's plans for $50 billion in tax cuts caused the UK bond market to collapse, she was fired after just 44 days as prime minister. Forced to resign. But if international finance has formed a new regulatory agency, its rival in power and influence is the Internet.

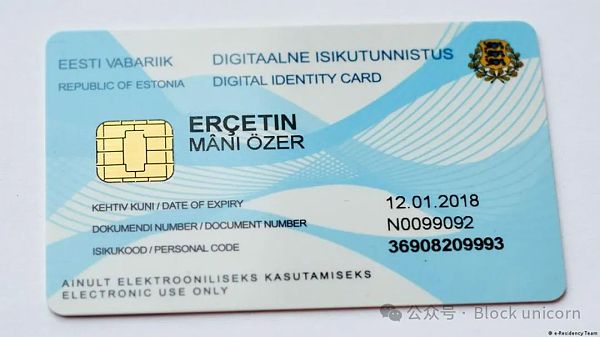

Since its inception, the "architecture" of global networks has made the landscape of contemporary governance more complex. The Internet is not only a communication medium, but also a transmission layer for new regulatory forces. Networked computing enables the creation and expansion of new norms, markets, and architectures at multiple levels of abstraction. For example, social media platforms have their own semi-automatic free speech policies that have nothing to do with the country's policies; while social media content includes an independent system of norms, including the diet of "beliefs (ideologies)" and "moral norms" on the Internet . Remote work provides new opportunities for civil rights arbitrage, while Internet-borne subcultures create imagined communities as powerful as any national identity. Even in places where law is closely integrated with the Internet, such as in places like China, national laws often have to catch up.

Estonia’s e-citizenship card can be obtained by applying online.

15 years ago, a new competitor entered the arena: cryptocurrency. In some ways, cryptocurrency protocols rehash the regulatory innovations of the Internet. But they also generalize the censorship-resistant properties of previous web technologies like BitTorrent and PGP. Cryptocurrency protocols cannot be tampered with by middlemen or higher-level institutions, and although the long arm of the law can force Facebook to expose our direct messages for inspection, or seize the hosting of pirated e-books, as long as there are miners running nodes, Bitcoin and Ethereum’s assets are accessible and inalienable; computational states are irreversible. In other words, these protocols do not respect the law. A cryptocurrency protocol is a currency and contract medium that does not require or verify state authorities. They create a new type of regulatory agency that is resistant not only to scrutiny but also to the law itself.

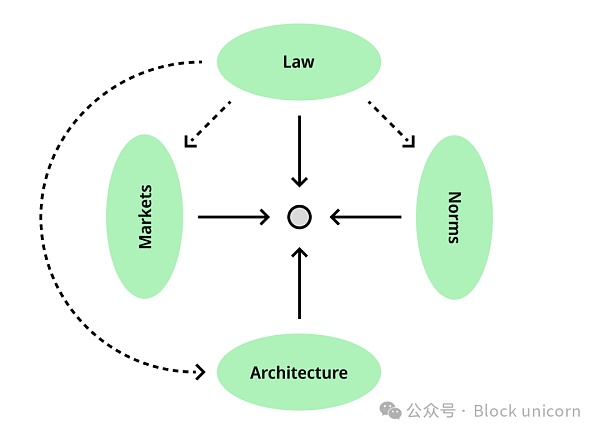

This is not to say that encryption protocols are merely criminal, lawless techniques. Resistance to the law is also what drives a positive vision of improving traditional organizations and solving social coordination problems by designing trustworthy neutral institutions—monetary systems, banks, and public resources—from the ground up. By “resistance to the law,” therefore, we refer to the resistance of Bitcoin and subsequent cryptographic protocols to the regulatory underlying framework that operates as a pervasive overarching in Lessig’s model. As blockchains resist national laws, they also create their own regulatory systems. With the law unable to intervene, the remaining three forces are free to regulate the institutional ecology of encryption protocols. Without a unified arbiter, let us take a look at some novel institutional dynamics that may arise from the protocol.

Three-body control issues

In the absence of laws, software architecture, markets, and regulations are uncontrolled. The interaction is responsible for what we call the cryptographic three-body regulatory problem.

1. An encryption protocol consists of a technically coded architecture with some distinctive features. Cencryption protocols are open source and permissionless, meaning anyone in the world with an internet connection can access them. They handle computation in a deterministic manner and introduce significant resistance to subverting the highly replicated state of the protocol. Protocol architectures are severely constrained in terms of interaction interfaces: they provide only limited and specifically defined facilities for interaction (e.g. application binary interfaces). This is one of the keys to understanding protocol governance: participating in a cryptographic governance system means ultimately interacting with smart contracts or blockchain code.

2. Crypto protocols are driven by a global 24/7 market. When users interact with cryptocurrencies, they do so through the deterministic logic of hard-coded market structures, which include token supply, reward functions, bond curves, lending and exchange rates, automated market makers, and more. The second control system. The requirement for blockchain state to be calculated by sending transactions means that certain markets and architectures (such as Ethereum) are tightly interconnected. Because of this, many crypto markets still evade legal regulation because the law cannot reverse processed transactions. The fusion of markets and programmable code also explains why incentive mechanisms are ideal for protocol design and the preferred tool for “stakeholder alignment.”

3. Finally, we have a social norms layer consisting of multiple layers of on-chain and off-chain communication Channels together constitute what we usually call “space”. The crypto community is filled with various subcultures: cypherpunks, gamblers, platform cooperativists, various forms of activists, e-girls, nascent Christians, post-internet artists, neo-rationalists, effective Altruists and accelerationists of all styles and speeds. Each group brings its own norms, and many design protocol-based projects to suit their political stance. Although each microculture has its own unique characteristics, most of them share one thing: an insistence on self-managerialism and anti-institutionalism. This norm appears to be part of what attracts different groups to crypto for the first time, even turning would-be bankers into advocates of P2P cash.

Because regulatory forces influence each other, different combinations can have an impact on the dominant incentives and long-term social development of a given system. Lessig pointed out that regulatory forces can sometimes "substitute" for each other: for example, the use of transportation vehicles such as speed bumps and traffic circles can be more effective than the police issuing tickets, but in the absence of the unified regulatory force of regulations, the ability to substitute will be lost. greatly weakened.

Cryptocurrencies lack this integration power. There is no underlying regulatory logic that translates collective concepts of justice into regulatory strategies that can be implemented in all areas. In its absence, the destabilizing interplay of norms, markets, and architecture generates new and often surprising institutional behaviors. Let's see how this three-body problem develops in the context of several protocols.

Case Study: Institutionalized Bribery at Curve

Curve is a DeFi protocol that distributes rewards at a fixed frequency. Earnings are distributed based on time-locked staking calculations: a user’s tokens multiplied by the lockup period determine their voting escrow(ve) power in terms of incentives provided to a specific pool.

Relevantly, the Convex protocol aims to increase rewards for CRV stakers and Curve LP, effectively creating a secondary market for voting. Through Convex, market participants in need of liquidity can pay users who have locked their funds in Curve to channel their liquidity voting rights. As a result, the community has adopted the terms of black markets and bribery to describe this system, which in fact describes the core institutional logic of the Curve/Convex protocol, setting accurate expectations for how to interact with it.

Curve demonstrates the novelty of the protocol as an institutional framework. In the absence of human management, the combination of programmed incentives and free markets introduces an institutional behavior that is expressly prohibited in legal environments—bribery. As a result, social norms are reoriented to validate and replicate this pattern. In other words, norms become indistinguishable from market incentives. These incentives are accepted and normalized, and from a de facto perspective no one attempts to limit or change this dynamic; it is simply allowed to operate. We mention this example not to support the bribery or verification veToken mechanism, but to point out that the core logic of the protocol and its popular understanding are actually consistent.

While there are many examples of unique and sometimes questionable institutional logic in the crypto space, this case demonstrates both the convenience and limitations of protocol regulatory influence. With all three forces aligned, even bribery can be seen as an acceptable outcome. But there is not always harmony between regulatory forces, for example, in the debate over NFT royalties, all three forces collided.

Case Study: The Erosion of NFT Royalties

Many popular The ERC721 NFT implementation uses a hard-coded royalty, paying the original author a small fee each time the NFT is resold. It’s a market structure designed to satisfy a specific normative proposition: creators should be rewarded for the value they create. Some of the largest NFT marketplaces and protocols respect these royalties and even give users the option to add additional tips to the original creator. However, crypto’s open-source, permissionless architecture makes it possible to “encapsulate” these NFTs in other smart contracts, which can then be sold and unsealed, thereby avoiding fees.

When NFT markets Sudoswap and Blur launched, their designers chose to implement these workarounds, ignoring existing norms and undermining other trading platforms. This competitive behavior forced OpenSea, the largest NFT marketplace, to follow suit and make royalty payments optional. The story has an unhappy ending, with crypto-loving artists feeling betrayed by the medium and the popular market. Market structures can be designed to conform to norms, but they cannot be enforced.

Protocol designers often assume that the market, code, and specifications will coexist harmoniously according to their own plans, often to the contrary. Unlike generally consistent legislation in a particular jurisdiction, the realm of agreement is one of anarchy and disorder. Protocols with different specifications compete for resources and attention, using incentives to attack each other, or collapse in accidental hacks, or in "manipulative pulls." In the rise and fall of NFT royalties, smart contracts only enforced fee payments for a brief period; ultimately they were unable to withstand the contingencies introduced by permissionless metagames. All contracts are incomplete, but this is especially true for smart contracts. Here, one aspect of technological infrastructure proved dominant.

In the absence of law, attempts to use other state-inspired tools such as constitutions, role appointments, and subjective rules often prove futile. Let’s look at one more situation where smart contracts overturn other institutional design patterns.

ENS is a protocol with national characteristics and has the characteristics of the ENS DAO constitution, "democratic" governance process and emphasis on public goods. These tools demonstrate a greater commitment to stakeholders: the norms and values of the ENS community are reflected through the protocol’s institutional behavior.

When a nasty tweet from ENS co-founder Brantly Millegan resurfaced 5 years later in 2021, it caused outrage in the crypto community. anger. Brantly Millegan discriminated against homosexuals and the ENS community wanted to vote him out, ultimately leading to a vote by ENS token holders to remove him from his position at the ENS Foundation, a legal entity registered in the Cayman Islands. Putting aside whether the actions were justified, what is interesting is the apparent inconsistency between the tacit normative expectations of ENS token holders and what the protocol mechanisms allow.

One of the controversial features of the vote to remove Millegan from the foundation's board was that part of the reason the proposal failed was because Brantly himself voted against the proposal . Without Millegan's vote as the largest delegate, a majority vote would trigger his removal. Although many in the ENS community expected Millegan to abstain, any legally binding social rules, such as a company's articles of association, must necessarily lie outside the agreement. The ENS "Constitution" does not take this scenario into account, and ENS airdrop participants must sign it in order to receive their tokens, and such contingencies are not designed into the voting system.

Although agreements can regulate certain behaviors, it does not mean that they have the full regulatory capabilities of the state. For example, linguistic rules such as charters, constitutions, and codes of conduct are extremely vulnerable in the absence of retroactive enforcement mechanisms for the law. Legal authorities use these texts to infer the intentions of the contracting parties, whereas agreements have no such ability.

The protocol includes various hardened architectural features to facilitate coordination. Likewise, the creation of digital property rights through programmable control enables a variety of permissionless marketplaces. However, as a protocol becomes more community-run and assumes more complex governance functions, the social challenges become more severe. In this case, the conflict cannot be resolved by programmed economic incentives alone, but requires additional discretionary logic related to community values. In short, when conflicts inevitably arise between these three forces, they cannot be resolved by traditional legal means.

Back to code issues

Us Institutions that regulate behavior through the deployment of effective power have been demonstrated, and in the absence of law, behavioral dynamics within the cryptosphere are the result of regulatory instability. While the law may not be entirely self-consistent, it at least provides a single judicial surface through which all other regulatory forces can be transformed. In the chaotic jigsaw puzzle of cryptographic protocols, people’s lives are more disconnected and risky than in the country’s comprehensive regulatory system. This hasn’t stopped brave souls from migrating their assets to the digital realm, but how do crypto citizens cope with the often contradictory results of the three-body system? The ability of agreements to credibly enforce discretionary principles is far less developed than that of states.

Readers will notice that in the three cases discussed above - Curve, NFT royalties and ENS, institutional behavior tends to "return to code" . What we mean by this is that regardless of the role that norms play in a protocol ecosystem, the ultimate determinants of institutional and user behavior are coding architecture and market incentives. In Curve, we see that "greed" behavior is a legitimate social norm implemented through the mechanism of vote buying. In NFT royalties, we see artist-backed royalties collapsing in price wars. And in ENS, the built-in token voting system overturned the ENS community’s normative stance on Brantly Millegan’s removal and abstention. When normative behavior cannot be enforced, it tends to revert to behavior imposed by other regulatory forces. Then, new social norms corresponding to existing structures will prevail.

Some consider this regression to be fundamental policy in the crypto space: "Any behavior allowed by the protocol's code and market structure is legal." .” Although this sentiment is rarely expressed in such a direct way, it is quite common among crypto users. In the case of Curve, this view does exist. This is also a time when people defend the right of hackers to take advantage of poorly designed protocols. As the Mango Markets hacker claimed, his team simply “operated a highly profitable trading strategy.”

However, regression to code does not always produce legal results, so it cannot always hold. In the case discussed earlier, the legality of the agreement ruling was precisely the issue. For example, it's not clear whether being unable to protect artist royalties is a good outcome. Many believe this is actually an architectural flaw, exploited by unscrupulous traders to bypass the good intentions of the designers.

The return to code erodes social norms, a consequence that explains much of the aversion to crypto. Even though protocols fulfill important social functions, such as providing affordable remittances and escaping an inflationary system, to the outside world “the space” appears greedy and rife with fraud. It is for this reason that encryption appears to be different from all previous human institutions. It is not simply "lawless" but a "norm-less" zone where morality is suspended, even if the current intention is to support the resilience of various social organizations.

The HEX token is an early example of the new discipline of Ponzi economics.

Thus, the widespread belief that any behavior permitted by the agreement is unquestionably legal is obviously harmful, but what is really behind this harmful belief is that The main culprit is the principle of credible neutrality. According to the principle of trustworthy neutrality, the fairness of a protocol means that all actions that occur within its scope are valid. This includes not only controversial governance outcomes, but also social transgressions such as hacking or fraud that are technically permissible and tolerated in the name of neutrality and permissionlessness.

This is not to say that we should not insist on censorship resistance as a fundamental technical feature. However, there needs to be a facility somewhere to prevent users from being victimized. Evoking trustworthy neutrality should not primarily have the effect of reducing accountability and putting users at risk. For example, one can support net neutrality, i.e. non-discriminatory packet transmission, without imposing a dark user experience model on users. The question, therefore, is where and how to apply this regulatory power? Any such consumer protection tool must ultimately be self-regulated by the protocol participants (interfaces, relays, solvers) who have a responsibility to the users.

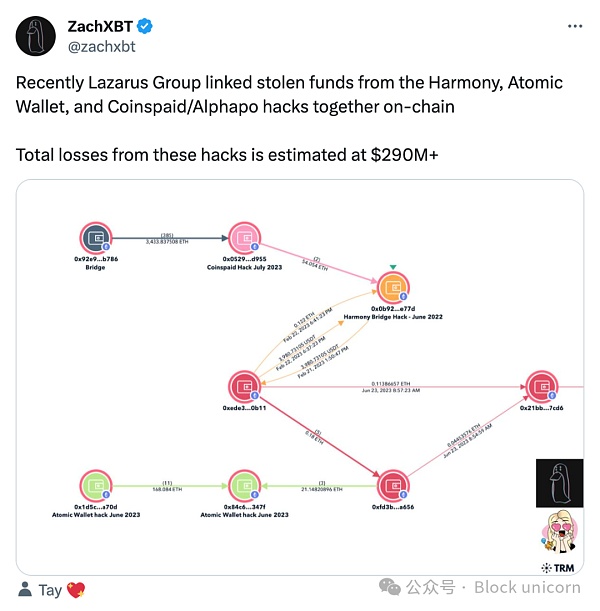

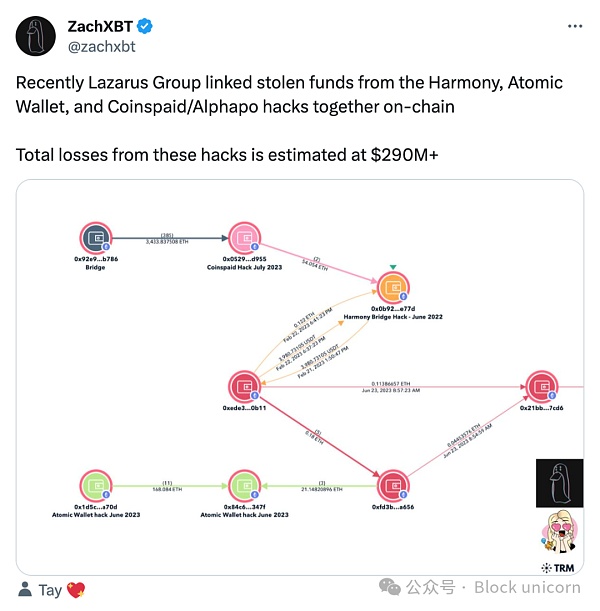

In discussions about trustworthiness and neutrality, some protocol designers and users hope to make the specification part of an effort to increase encryption's self-regulatory capabilities. Given the ineffectiveness of normative regulation, a small group of self-regulatory parties have stepped forward to promote different forms of social well-being. In the Ethereum ecosystem, two institutions in particular have attracted the attention of society: the public goods project Protocol Guild and the private detective ZachXBT.

Notifying others about scammers and delisting users of scammer front-end interfaces is acting from an ethical standpoint and is intended to protect others. ZachXBT is a well-known figure conducting research on-chain, documenting and exposing scammers that the crypto community has previously turned a blind eye to. While ZachXBT is only one participant, NounsDAO’s vote to fund him can be seen as a broader attempt to normatively block malicious behavior. In fact, NounsDAO has endorsed a crypto-native “community safety officer,” solidifying industry norms and making it harder for scammers to build a business.

Protocol Guild, on the other hand, encourages prosocial behavior. The Protocol Guild is a public goods project designed to provide financial support for Ethereum’s core infrastructure. Rather than leveraging protocol mechanisms and incentives to promote themselves, operators work behind the scenes to create social alliances between crypto projects. Sponsored projects choose to share the responsibility of funding the core development on which they all depend, promoting a philosophy of generosity and mutual benefit.

Nouns’ sponsorship of ZachXBT and the Protocol Guild is one of the few viable examples of the crypto industry regulating itself to limit its worst possibilities, by fostering norms of correctness : respectively making web3 a secure environment and supporting Ethereum core development. These norms do not arise from trustworthy neutrality but from the virtues of opinionated citizenship that intervenes in critical ecosystem-wide issues. Furthermore, the Protocol Guild and NounsDAO substantially justified this stance through the resources and user touchpoints they directly control. In both cases, capital allocation mechanisms elevate normative commitments above quantifiable financial incentives. They show that it is possible to build consensus on norms and promote compliance even in the absence of laws. In short, technical agreements are not the only answer in themselves, but serve as the basis for broader social agreements.

Space limitations

Although Protocol Guild and ZachXBT etc. Efforts have been successful in promoting positive norms, but we believe they represent the limits of social agreement based on a trustworthy neutral society. This cultural desert is an unsuitable place for building a new framework of social norms. Both efforts are entirely voluntary, and the crypto “space” as a whole does not share their view of civic virtue.

From this perspective, we can see that DAO is going in the wrong direction: because cryptographic language has never been rooted in a specific social agenda, "DAO tools" 's founders got lost in the meta-circular language of exploring their own institutional possibilities. "What is a DAO?" is a question that has never been answered. Likewise, building a “cryptostate” is an impossible fantasy. A country is a legal jurisdiction and a group of people with a common identity and culture; while an encryption protocol is an institutional technology, this "space" is not an independent society.

The idea that cryptocurrencies are viewed as a “space” to build on is the biggest limitation to their success. This perception is deeply ingrained in the crypto space, even amid the desire to “attract the next billion users.” As we’ve shown, the misaligned regulatory structures in today’s crypto space that are ill-suited for mass adoption are no longer “early stages” at all. If crypto’s only goal was to create a non-state property system, it has already succeeded. But it remains far from being able to produce non-state institutions that are embedded in and contribute to social life. Crypto needs to go to the people, not the other way around, which requires a complete change of direction.

Contrary to the years-long trend of moving everything to the blockchain, crypto needs to drastically reduce the scope and create a richer and Active social background. In other words, the root cause of crypto’s three-body regulation problem is not just a lack of technical infrastructure, but also the culture of separation itself. Crypto is a bank run on an entire crony-riddled financial sector, but this flow of assets should be into local communities, not into abstract digital “spaces.” From talk of “putting real-world assets on the blockchain” to regenerative finance attempts to single-handedly change the world through digital abstraction, many in the industry often misunderstand the nature of the problem.

The question is not how to add norms or social agendas to the crypto “space”, but how to integrate crypto with the broader institutional ecology. When we imagine a crypto that is more integrated into social life, we are not imagining a disconnected economy accessed through screens, but we are imagining interactions, organizations that are more seamlessly integrated with our everyday institutions, supporting the interactions we already live in and non-exploitative exchange media and real value production of social life. If a return to code is the only binding rule, these types of organizations simply cannot grow.

The free market, license-free frontier will always be ungovernable. But the space for peer-to-peer digital institutions to survive is shrinking rapidly as the law intrudes on crypto's legal gray activities. Inexplicably, the original cypherpunk vision of reliable non-state institutions might survive only through engagement with a culture richer than crypto itself. If so, this next phase will certainly require protocols that go beyond incentives and smart contracts.

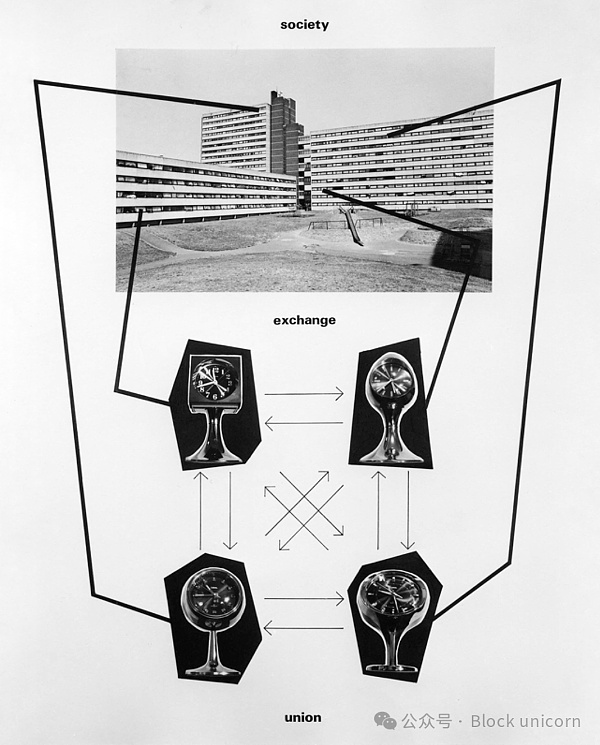

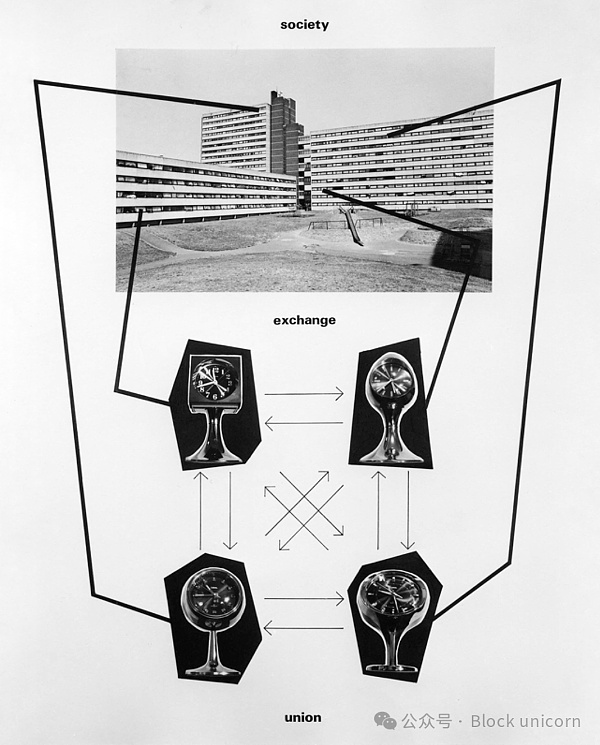

Stephen Willatz - Our Human Home 1990:

"When I was working in Berlin in the late 1970s, my main Working with people living in modern apartment buildings on the west side of the city - I began to notice that in these apartments people were surrounded by objects that made them feel modern; "in the moment". They were not necessarily heavy in design objects, but they are objects that exist in their private social space—objects that make them feel connected to the world they live in and that are monumental in their own way—rather than as objects that contain social space Same as architecture.

I became interested in the dichotomy that emerged in this context: the concept of "people and objects" and "people as objects". So I Starting to record these thoughts, I then stumbled upon the Home Court building in Feltham, considered to be the largest single housing project in Western Europe at the time; a brutal, soulless place that entirely expressed the idea of the human as object. Of course, individuals in this vast place lead complex social lives, but the visual language of the architecture itself is a simplified, highly institutionalized one.

With In the meantime, I've been working on some still life paintings using modernist objects: looking again at the debate between objects and people, and the idea of objects as immortals, and then I went from there to make a series placing objects in three different human networks , each type of network generates a different way of perceiving relationships within a building - for example, a network of conflict or a network of exchange, etc. The result is the work of these three groups. In the background is a photo of the home, in the foreground I am Several sets of clocks found in an apartment. These clocks carry a built-in concept of time and the passage of time: I then arranged them into these three networks, showing three different ways of observing life there.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance