CoinGecko Expands Reach with Zash Acquisition

The crypto data platform plans to integrate new endpoints into its crypto data API by Q2 2024, covering various aspects of NFT data across major platforms.

Davin

Davin

Source: Block unicorn

When my non-crypto acquaintances ask me about my fascination with cryptocurrencies, I often have to stop and think about how to explain it.

The crypto industry is a multifaceted beast. It has a deep technical core, involving different fields such as cryptography, computer science, and protocol development. It also has a highly financialized appearance, with its most notable feature being the circulation of liquidity and the monetary value associated with that liquidity. But the aspect of crypto that fascinates me most, and the most difficult to explain, is its cultural potential.

The use of the word "potential" is deliberate. Because we are not there yet. Crypto culture is still in its infancy, prone to hysteria (madness), as well as cult-like figures, charlatans, and outright criminals. Even at its mildest, the cultural scene here seems to be full of nonsense and empty rhetoric.

That said, I think all of the above is a feature rather than a bug. With or without cryptocurrency, modern life is already full of bullshit — it permeates our popular culture and even our workplaces. Wherever money goes, scammers of all stripes follow. Crypto is not, therefore, inherently more prone to scams or rogue behavior. It’s just that its open and permissionless nature allows our most basic and banal characters to operate without guilt.

The purpose of this article is to share my perspective on why, despite these shortcomings, I still think there is more to cryptocurrency’s cultural potential. I also want to do this in a non-technical but thoughtful way so that those who are not familiar with the field can easily understand it.

In this regard, I want to offer an alternative framework for thinking about crypto — that it should not be seen as a disgusting or hostile place that must be avoided at all costs, but rather as an open, free workshop where tools are available to anyone. They can be used to cultivate more lasting and vibrant forms of digital culture.

My basic premise is this:

Cryptocurrencies offer an improved set of tools for cultural production on the internet.

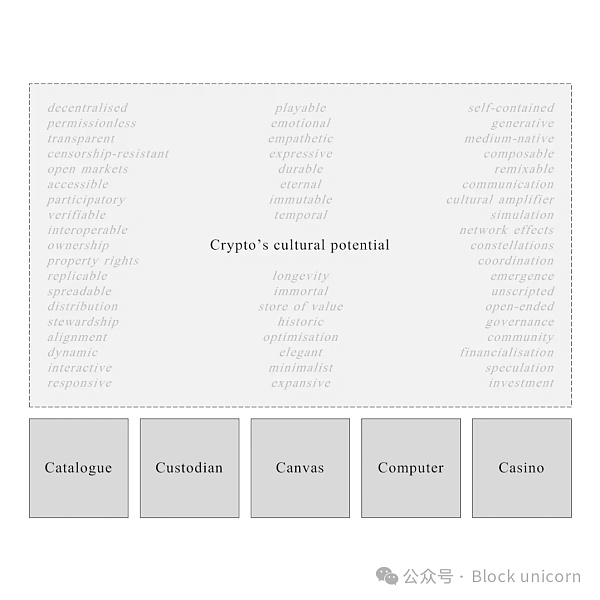

You can conceptualize these tools in terms of the five “Cs,” representing the blockchain’s functions as: (i) catalogue, (ii) custodian, (iii) canvas, (iv) computer, and (v) casino.

Anyone is free to use these tools to contribute to digital culture, ultimately creating something meaningful that can be passed down to future generations.

A sea of motherfuckers on platform 24 (2019) is a work by XCOPY that reflects the artist’s distinctive glitch aesthetic—visually stunning, thematically horrifying, with an intensity and edge that makes it indisputably XCOPY.

The anonymous artist had been posting his animated works regularly on Tumblr for nearly a decade before his first auction in 2018, thus accumulating a cult following that has underpinned his explosive success in the crypto art world in recent years. Many of his works use flippant and witty titles to further increase their potency, and often get to the heart of contemporary cultural trends, particularly on topics related to cryptocurrency, see for example All Time High in the City (2018) and Right-click and Save As guy (2021).

Sociologist John Scott defines culture in the Dictionary of Sociology as “everything that is socially rather than biologically transmitted in human societies”. I like this definition because it’s concise and to the point. Culture is essentially everything we pass on to others through non-biological means, whether material or immaterial, such as stories, art, music, and other shared practices or rituals.

The process of cultural development takes time, and usually only becomes “culture” once relevant objects, practices, or ideas have been passed down from one generation to another. However, in the context of digital culture, this time dimension is greatly compressed. The consumer internet has not existed for more than one individual’s lifetime. Digital cultural objects or experiences are also more ephemeral due to the speed at which information flows online and the rapid changes in the infrastructure and interfaces we use to interact with the internet.

As you cite as an example: forum signatures or “signatures” are banner graphics that users can attach below their posts on online forums, and when I was a teenager, they were very popular in online gaming forums. I remember making a lot of these signatures and posting them in the forums I participated in to increase interaction. There were even competitions where we could “duel” with other users to see who could get more votes on our submitted signatures. Unfortunately, as I’ve changed computers over the years, I’ve lost my signatures, and the ones I uploaded to image hosting sites have long since disappeared. Many of these gaming forums have also closed down as other platforms have emerged to capture the attention of subsequent generations of teenagers.

So the ebb and flow of digital culture is very real. Many online items or experiences simply cannot stand the test of time because the internet is vulnerable to bit rot at web scale.

I emphasize the ephemeral and volatile nature of digital culture not because I think cryptocurrency can help to fully alleviate these structural conditions (it can’t), but because I think it provides a well-balanced set of tools that can help improve the process of cultural production on the internet despite these conditions.

My mental model of the cryptocurrency cultural production toolbox can be summarized by five Cs, each of which represents an analogy for the functionality of a blockchain. I believe this provides a simple and comprehensive framework for appreciating the potential of cryptocurrency as an enabler of digital culture.

Blockchains are not difficult to understand conceptually. I like to describe them simply as databases with some special properties. In short: the data held by a blockchain is distributed across the network (decentralized), anyone can add data to it (permissionless) as long as they follow the rules set out in the codebase, and its data can be seen by everyone (transparent), but no one except the data owner can tamper with the data (censorship-resistant).

Open and verifiable records

These special properties make blockchains inherently suitable for use as records of online cultural objects:

The transparency of blockchains allows anyone to view these records, which is consistent with the open nature of the Internet. Listings in such records are also not static and are automatically updated as people transact with the listed items. In addition, anyone can query the history of all transactions involving each listed item on the blockchain, which helps to form a more open market around online cultural objects.

The permissionless nature of blockchains also means that anyone can contribute to lists. The barriers to adding to such records on blockchains are low, so they are not easily restricted by barriers, which will help make digital culture more accessible and participatory.

Given the censorship-resistant nature of data on a blockchain, users can also have greater confidence that listings on the blockchain are authentic. While blockchains cannot fully determine the provenance of digital objects off-chain, as some trust assumptions are still required to link a blockchain address to a specific creator, they provide a nearly unforgeable relationship between digital items on the blockchain and blockchain addresses. This reduces the burden of verification for users - if we see that a creator has published their blockchain address on multiple independent sources, such as on social media and digital art galleries or secondary markets, we can be reasonably certain that a listing created from their blockchain address is authentic.

Such listings work on blockchains by using common technical standards. For Ethereum and other similar smart contract blockchains, this is achieved through tokenization. The ERC-721 token standard (or equivalent standards for other blockchains) enables digital information to be tokenized as non-fungible tokens (NFTs), each of which is similar to a listing in a directory. For Bitcoin, ordinal number theory allows digital information to be inscribed on a single satoshi (the smallest subdivision of a Bitcoin). Each inscribed satoshi (also known as an ordinal) is similar to a listing on a directory.

Interoperable Records

Because such listings are based on common technical standards, namely NFTs or ordinals, their related records can be interoperable across multiple platforms on the same blockchain. You can browse them and trade them using different applications, similar to how a jpeg file can be opened by multiple image viewing or editing software.

This interoperability is a powerful feature because it allows the distribution of cultural items on the blockchain to be decentralized across multiple platforms and marketplaces, such as: OpenSea, Blur, Magic Eden. As creators and consumers of these items, we can choose which platform or marketplace to use based on our needs. We are also not bound by the policies of a single market, nor will we be catastrophically affected by platform downtime.

In summary, as an open, verifiable and interoperable catalog of digital items, cryptocurrency has the potential to become a comprehensive map that helps participants navigate online culture. I believe this is very powerful because then we will have more autonomy to decide how we want to produce and consume this culture. This is why I think we should start to build the starting point of on-chain culture more consciously.

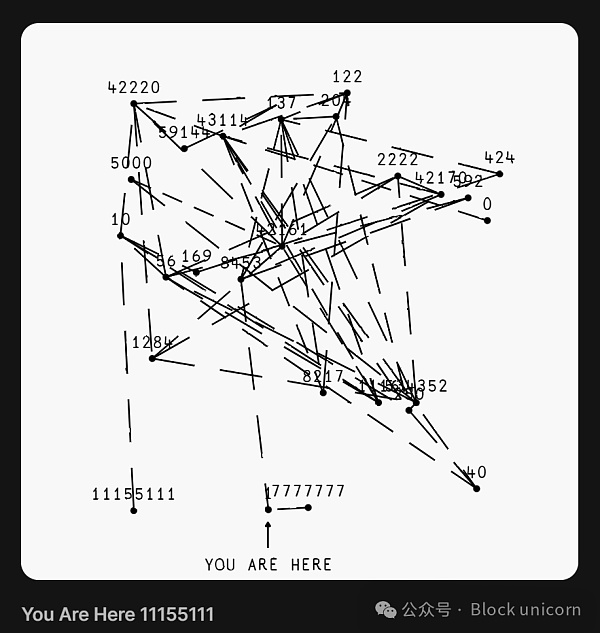

《You Are Here (2024)》is a conceptual art work created by 0xfff, which explores the theme of interoperability in different ways across different blockchains. With the help of LayerZero, a protocol that enables applications and tokens to interoperate across blockchains, the tokens in each project can be bridged between several blockchains compatible with the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM). Every time a token is transferred through a bridge, a record is left on it, like an archive that can trace the bridges it has passed through and the borders it has crossed in the past.

In the above-mentioned works, "You Are Here 11155111" belongs to the artist. Of the project’s 34 tokens, it is the most bridged (66 times) at the time of writing. Its intricate trails resemble a well-traveled map. Collectively, they hint at the vast space that creators can tap into to design new and interesting cultural experiences thanks to blockchain’s interoperability.

In addition to directories, blockchains also act as custodians. They enable us to own digital items

Think about this question for a moment, especially how contradictory it sounds. Digital items are inherently reproducible—anyone can “right-click and save” a digital file, creating an unlimited number of copies of the file on the internet. As a result, ownership of such online digital items has always been very fragile.

Digital Items as Property

Blockchains can help separate ownership and usage rights of digital items. You can think of NFTs or ordinals as tamper-proof certificates of ownership on a blockchain. Given that only someone who controls the private key to a blockchain address can conduct transactions using that address, you absolutely own any NFT or ordinal held by that blockchain address as long as you control the private key. The NFT or ordinal you hold cannot be held by any other blockchain address. Therefore, digital items associated with NFTs or ordinals can be owned like any other physical property.

In fact, Singapore courts have recognized NFTs as property, paving the way for owners to have legally enforceable property rights over their digital assets on the blockchain, both financial and cultural.

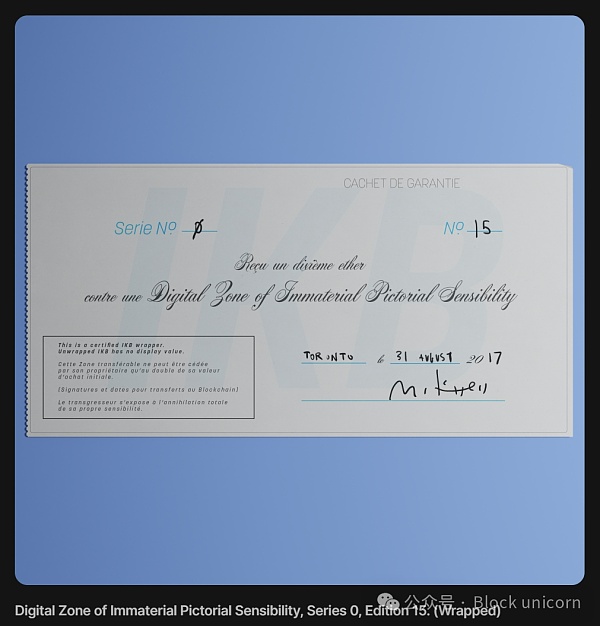

Digital Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility (2017) by Mitchell F Chan is a parody of Yves Klein’s Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility (1958-1961), a conceptual artwork that raises many questions about the nature of ownership.

Yves Klein created several “zones” made up of spaces that could only be purchased with pure gold. Upon purchase, Klein would issue a receipt to each collector, who then had two choices: (i) keep the receipt, or (ii) participate in a ceremony in the Seine River in Paris, in which the collector had to burn the receipt and Klein would throw half of the gold into the river in front of witnesses. In Klein’s view, true ownership of an artwork means that the work must be fully integrated with the owner, making it absolutely and intrinsically theirs. This means that the physical record of the artwork, the receipt, must be destroyed so that the work cannot be resold and exists independently of its original owner.

For ‘Digital Zone’, Mitchell F Chan created 101 works that display a pure white blank screen when viewed online. Each work can only be purchased with ETH through the artist’s smart contract on Ethereum, and in return, collectors of each work will receive a token. Similar to Klein’s ritual, collectors can choose to destroy their tokens through a ritual function on the artist’s smart contract, and Mitchell sends the ETH accordingly.

Mitchell’s transformation of Klein’s ‘Zone’ into a digital environment highlights the increasing intangibility of our contemporary culture, where virtual experiences have been accepted as a substitute for physical experiences. In this context, the work invites us to consider the separation of the commodity form of an artwork from its experiential form (both of which are intangible in different ways), and how this affects collectors’ relationship to and value of the artworks they own. Indeed, one has to ask: what do we really own when we buy an NFT of an intangible digital artwork? (Note: Mitchell has also published a 33-page article to accompany the piece, which is worth a read if you’re interested in more details about Klein’s “The Zone” and his work.)

Tangible Ownership, Unlimited Distribution

Even though cultural objects on the blockchain can now be legally or practically owned, they still retain the features that their digital nature allows, namely their reproducibility and spreadability. In other words, cultural objects on the blockchain can be both abundant and scarce at the same time. They can be widely distributed and used, while each object can only be owned by one blockchain address at a time.

This unique combination of properties turns our traditional view of the value of property on its head. In a digital environment, tangible, scarce objects may not necessarily be viewed as more scarce, and therefore more valuable. Instead, the more they are shared, the more valuable they may become. After all, not everything online can go viral.

Writer and cultural studies scholar McKenzie Wark writes about this in relation to art collecting:

“What is more interesting is to consider how the uniquely communicable properties of digital objects can be turned to advantage, making them collectible as well. Paradoxically, objects whose images are widely circulated are rare objects, because few objects have images that are widely circulated. This can be exploited to create value for artworks that are not traditionally rare and unique. The future of collecting may lie not in owning something that no one else has, but in owning something that everyone has.”

Nyan Cat is a popular internet meme based on an animated cat with a body shaped like a cherry pie that flies through outer space with a rainbow trail. On the tenth anniversary of Nyan Cat’s initial release (April 2, 2011), its creator, Chris Torres, recreated the animation and sold it as an NFT through auction. The final winning bid was 300 ETH, demonstrating the enormous value that can be derived from popular internet memes.

Custodian of Ownership, Manager of Value

By acting as the custodian of the necessary information needed to prove ownership, blockchains not only make it easy for digital cultural objects to be traded online, but also for them to accumulate value as digitally native property. Just as how property in the real world underpins the vast accumulation of wealth in our society, property in digital culture will similarly become the foundation for how we grow, maintain, and distribute value on the internet.

When we are able to enjoy stronger and more secure ownership of our assets with the custodial power of blockchains, you can be sure that we will do our best to maximize the value on them. As blockchains become custodians of digital culture, the owners of its constituent cultural assets (at least those with a long-term mindset) will naturally be incentivized to become its managers.

It will certainly be interesting to see if ownership on blockchains can drive coordination between creators and consumers of cultural objects and create a venue for financial and cultural capital to unlock new forms of creativity and collective meaning-making. If this can be sustained over the long term, I am optimistic that this coordination can have a positive impact on the development of digital culture.

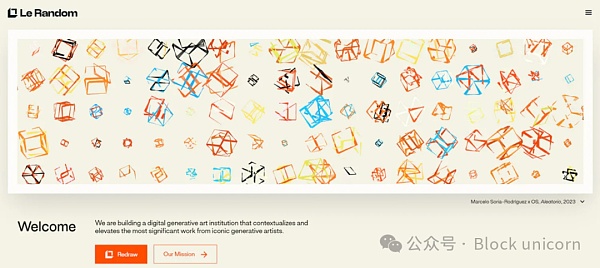

Screenshot of Le Random's homepage

Screenshot of Le Random's homepage

Le Random was founded by anonymous digital art collectors thefunnyguys and Zack Taylor and is positioned as the first digital generative art institution, consisting of two components: (i) a collection of generative artworks on the blockchain that conveys the depth and breadth of the generative art movement; and (ii) an editorial platform that seeks to understand the movement's place in art history and celebrate its cultural significance. The name "Le Random" is a nod to the late generative artist Vera Molnar, who once said that randomness was a key component of her practice.

Le Random's attention to collecting, contextualizing, and elevating generative art on the blockchain is remarkable. Its impressive collection is meticulously catalogued and beautifully laid out on its website. The Generative Art Timeline being developed by Le Random’s editor-in-chief Peter Bauman also provides an impressive gallery of generative art, from its pre-modern origins to the current era of blockchain as an artistic medium. The editorial articles on Le Random’s website are also in-depth and timely, including nuanced reviews and insightful interviews with artists. All in all, Le Random is one of the outstanding examples of blockchain digital art collectors, as well as passionate stewards of the field.

Blockchains are not just a platform for online trading and ownership of cultural objects, they should also be seen as an independent creative medium in their own right. They are canvases to which data (the building blocks of our digital culture) can be linked or directly inscribed.

In most cases, digital objects cannot be stored entirely on the blockchain. Due to the cost of uploading large amounts of data within the limited storage space of the blockchain, the actual media files underlying the NFT are usually hosted off-chain, for example, on decentralized file storage platforms, the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) or Arweave. If the files on these external storage platforms become corrupted or disappear entirely, this would render such NFTs unlinked (pointing to a ethereal token).

Despite this risk (which is somewhat mitigated by pinning for IPFS-based NFTs), I still think blockchains can serve as a fascinating canvas for digital culture.

Dynamic Digital Items

For me, the appeal of digital items on the blockchain goes beyond simply thinking of tokens as constructs that point to media (e.g., images, videos, or songs). What is fascinating is that digital items on the blockchain can, in fact, become dynamic in meaningful ways, even as the owner’s sovereignty over these items remains intact.

The design space for such dynamic digital items is vast. Creators can design these items so that the cultural messages they embody can transform based on the owner’s own input or in response to other events on the chain. This makes digital culture come alive for the individual owner or consumer, giving them the power to shape their digital experience while also connecting them to a larger shared reality.

There is a clear use case for such dynamic digital items in gaming, which already plays a significant role in our digital culture.

(Image credit: Axie Infinity Media Pack by Sky Mavis)

(Image credit: Axie Infinity Media Pack by Sky Mavis)

Axie Infinity is a blockchain-based game centered around playable characters called Axies that can battle and breed to earn in-game resources and collectibles. Each Axie is represented by an NFT on the Ronin blockchain and can be upgraded using points called Axie Experience Points, which are earned through gameplay. Higher-level Axies will be able to upgrade more parts, effectively making them dynamic NFTs that can improve with time, effort, and skill.

Other use cases include collectible objects that respond and interact within their digital environments; and in the art world, artists use mechanisms associated with cryptocurrencies to provide commentary or perspectives on blockchain as a creative medium and shared cultural space.

Finiliars (Finis for short) are a group of digital characters that change their emotions and expressions based on changes in the price of a specific cryptocurrency. Finis were originally created and exhibited by artist Ed Fornieles in 2017, and then updated, expanded, and launched as NFTs in 2021. Overall, Finis are designed to map out the abstract financial flows that make up global capital, especially in the cryptocurrency space. Their cute appearance also tempts us to form an emotional connection with them, forcing us to reflect on the relationship between empathy and financial investment.

The Fini project team has also collaborated with other crypto projects to launch special edition Finis. For example, Zapper Finis (Frazel and Dazel) are open-edition NFTs launched in partnership with Zapper, a platform that helps users track the value of their cryptocurrency portfolios. Frazel and Dazel ’s expressions and movements reference changes in the value of their owners’ portfolios.

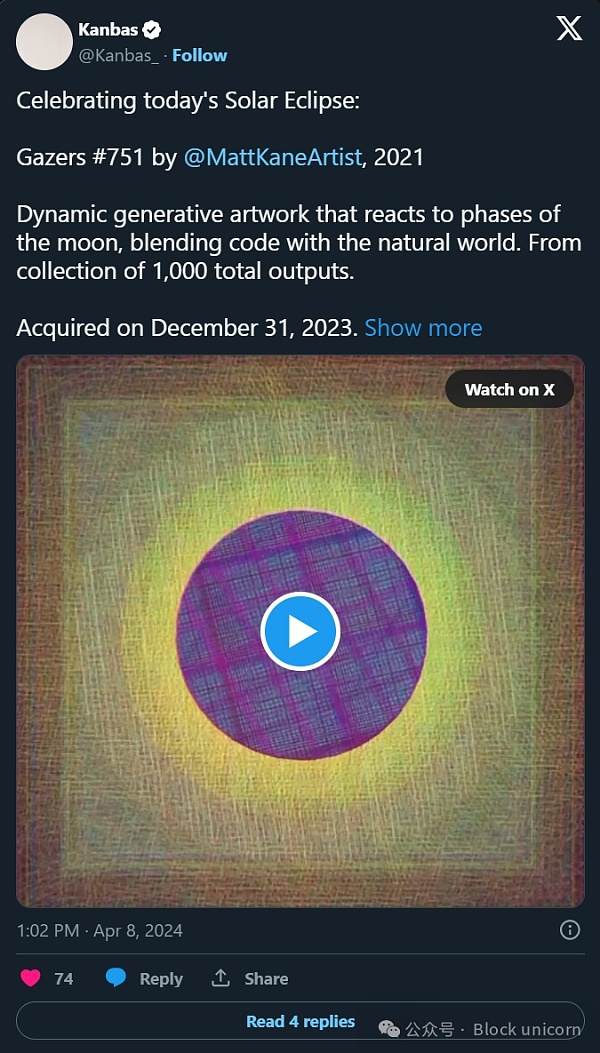

Gazers (Gazers) (2021) is a long-form generative art project by Matt Kane, consisting of 1,000 code-based artworks released through Art Blocks on the Ethereum blockchain. Each artwork references a lunar calendar, evolving dynamically with each day and phase of the moon. Gazers draws on humanity’s long-standing connection to the moon as a marker of time, highlighting the brevity and urgency of the present moment while prompting us to look up and reflect on the future—towards our own version of the moon.

Gazers #751, a static version of which is shown above, was most recently acquired by anonymous digital art collector Kanbas. During the April 8, 2024 solar eclipse visible from North America, Kanbas posted a video showing Gazer #751 burning with a flickering, glowing halo (see tweet below). It’s still a stunning sight, and one that shows how digital art on the blockchain can provide dynamic experiences that connect our digital and physical realities in delightful ways.

Durable Digital Items

On the other hand, there is another interesting subset of digital items on the blockchain that are designed to be extremely durable, so they are virtually eternal or immutable.

The notable feature of these durable digital items is that they continue to exist as long as their underlying blockchain remains operational. This is because the essential data required to render these digital items is stored directly on the blockchain, so they have few external dependencies.

In some cases, such items may still rely on widely distributed databases or development tools, such as some of Art Blocks’ generative art NFTs. That said, in general, blockchains provide a comprehensive canvas for these items to have all the necessary resources in place to achieve their intended expression.

For on-chain NFTs on Ethereum and similar smart contract blockchains, they do not point to off-chain or externally hosted media files, but rather only link to on-chain data, which is typically stored in a smart contract on the same blockchain. For Bitcoin, the data behind the ordinal is recorded directly as metadata in the transaction of a specific satoshi. In this regard, all ordinals are almost always immutable, unlike NFTs that rely on the data they link to.

Anyway, what interests me conceptually about such on-chain digital items is the temporal dimension—how they force us to consider the longevity of our digital experiences, which are often ephemeral. It seems plausible that on-chain digital items on our most Lindy blockchains, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, will outlive any of us alive today. They may hibernate, but they will never die. Even if their owner loses the private key, they don't disappear, they just become immovable. *Block unicorn note: The Lindy effect (also known as Lindy's law) is a theory that the longer something exists, the longer it will last.

With this in mind, I really think about the type of meaning we will give to on-chain digital cultural items that can transcend our personal lives. When they are owned and traded on the blockchain, what will be preserved in their memory? How will the relationship between their on-chain persistence and off-chain cultural heritage evolve over time?

The featured five pennies have been converted to ordinal numbers. (Image credit: sovrn.art)

The featured five pennies have been converted to ordinal numbers. (Image credit: sovrn.art)

CENTS (2024) by artist Rutherford Chang centers on the form of placing 10,000 cents on 10,000 satoshis, using ordinals as a medium to immutably connect the smallest units of the U.S. dollar and Bitcoin. Inspired by the difference in value between the metal value of copper pennies minted in 1982 and before (now about 2.5 cents) and their stated monetary value (about 1 cent), the artist selected 10,000 pennies that were no longer in circulation and made an archival record of them. Their images were then immutably engraved on the satoshis as ordinals, while the actual coins were melted down and cast into a solid copper block.

In addition to being a commentary on the perception of material and immaterial value in different contexts, CENTS is also a meditation on the impact of time on value. Rutherford Chang himself spoke about collecting pennies back in 2017. More importantly, the sense of history conveyed by CENTS gives it great weight. Each penny, while homogenous in nature when it was made, now bears unique traces of the passage of time in the hands of successive owners. As such, CENTS can be considered a generative work of art, "shaped by algorithms worn by the world," as collector become.eth wrote in a tweet.

Furthermore, the story of each penny does not end with its transformation into a digital artifact, as it will have a new history on the blockchain, an object of ownership and transaction in a new digital and physical society. As an enduring digital object that connects multiple temporal and economic contexts, CENTS undoubtedly has the potential to become the leading art collectible on Bitcoin and be seen as a valuable store of value in the future. CENTS was launched on sovrn.art in partnership with Inscribing Atlantis and Gamma.

According to the prompt "A large commercial aircraft flying in the blue sky", a set of 8 images created using the alignDRAW model. (Image source: Fellowship)

According to the prompt "A large commercial aircraft flying in the blue sky", a set of 8 images created using the alignDRAW model. (Image source: Fellowship)

According to the prompt "A large commercial aircraft flying in the rain", a set of 8 images created using the alignDRAW model. (Image credit: Fellowship) alignDRAW is an AI model for text-to-image generation created in 2015 by Elman Mansimov and a team of developers after Elman completed his undergraduate coursework in computer science at the University of Toronto. Published in a 2016 conference paper, the model is widely considered the first text-to-image model, laying the foundation for today’s wide variety of easily accessible AI tools for image and video generation. As these generative AI tools continue to transform image creation and our visual culture, alignDRAW stands as a milestone marking the beginning of this paradigm shift. With this in mind, Fellowship has partnered with Elman Mansimov to mint all 2,709 images created from the alignDRAW model as NFTs on the Ethereum blockchain in 2023. 168 of these images were generated from 21 unique text prompts, each in sets of 8 images, published in the 2016 paper. The other 2,541 images were generated from 21 text prompts (15 of which were unique and 6 matched the prompts in the paper) and uploaded separately to the University of Toronto website in November 2015.

According to the prompt "A large commercial aircraft flying in the rain", a set of 8 images created using the alignDRAW model. (Image credit: Fellowship) alignDRAW is an AI model for text-to-image generation created in 2015 by Elman Mansimov and a team of developers after Elman completed his undergraduate coursework in computer science at the University of Toronto. Published in a 2016 conference paper, the model is widely considered the first text-to-image model, laying the foundation for today’s wide variety of easily accessible AI tools for image and video generation. As these generative AI tools continue to transform image creation and our visual culture, alignDRAW stands as a milestone marking the beginning of this paradigm shift. With this in mind, Fellowship has partnered with Elman Mansimov to mint all 2,709 images created from the alignDRAW model as NFTs on the Ethereum blockchain in 2023. 168 of these images were generated from 21 unique text prompts, each in sets of 8 images, published in the 2016 paper. The other 2,541 images were generated from 21 text prompts (15 of which were unique and 6 matched the prompts in the paper) and uploaded separately to the University of Toronto website in November 2015.

The Fellowship designed a technical architecture that enables each image to be stored on-chain in its raw byte format, without alteration or enhancement. This was done in an incremental manner to take advantage of periods of low gas prices on Ethereum. By persisting and immutably saving alignDRAW images on the Ethereum blockchain, this approach affirms its historic role in ushering in a new era of human-machine collaboration where science and art merge.

Another interesting angle to perceive such on-chain digital artifacts is how their creators work within the technical limitations of blockchain data storage. The artistry that underpins these artifacts lies in optimizing the data to utilize every byte in the most elegant way possible to realize the creator’s creative vision.

As Chainleft, a data scientist and on-chain artist, describes it in an article: On-chain art is “a tribute to the timeless belief that in the small, we capture the infinite”. Indeed, from bits and pieces of blockchain space, we may be able to sow the seeds of broader and more enduring forms of digital culture.

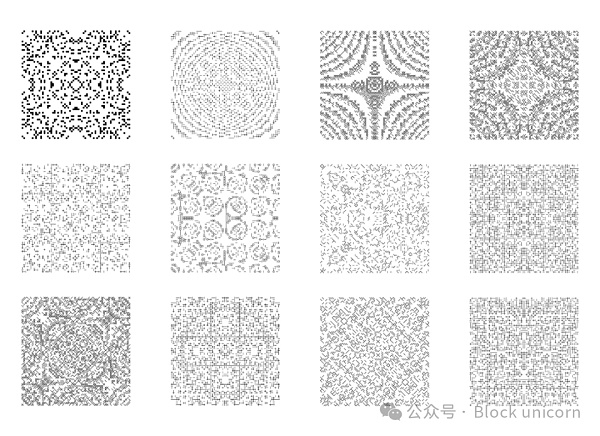

A selection of Autoglyphs. (Image credit: Curated)

A selection of Autoglyphs. (Image credit: Curated)

Larva Labs’ Autoglyphs (2019) began as an exploration into creating “completely independent” artworks that could operate within the strict data storage constraints of the Ethereum blockchain. The result is a highly optimized generative algorithm — which lives entirely within a smart contract — that can generate text patterns in ASCII format. This text pattern can then be transformed into an image based solely on the instructions encoded in the smart contract.

This approach pays homage to early generative artists such as Michael Noll, Ken Knowlton, and Sol LeWitt, whose work offers a perspective on artworks as systems rather than as representational works of art. In turn, Autoglyphs, as an independent medium-native system for creating, owning, and distributing digital art on the blockchain, has inspired many generative artists to continue to push the boundaries of blockchain as an art medium. No wonder Autoglyphs has been likened to prehistoric cave paintings on-chain.

Curated, a fund that collects crypto art, also has a concise editorial outlining the main features of Autoglyphs, which is a good starting point for understanding its visual output and understanding its collectible value.

Pushing the concept of the canvas further, we can also think of the blockchain as a computer.

By computer I do not mean simply a processing device that simply executes instructions within fixed parameters, but a broader concept that dates back to the early vision of personal computers proposed by computer scientist J. C. R. Licklider while working at the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) in the early 1960s. Early 1960s:

“Computers are destined to become interactive intelligence amplifiers for all people on a global scale.”

There are two key concepts worth emphasizing here:

First, computers are not only information processors, but also intelligence amplifiers - a platform that enables a more dynamic, learning-by-simulation approach to thinking, which is what computing enables.

Second, computers are communication devices, giving us the ability to coordinate with others in a larger network.

Let’s analyze them in detail in the context of exploring how the computational possibilities offered by blockchains shape digital culture.

Composable Digital Objects as Cultural Amplifiers

Ethereum has been described as a “world computer” since its early days. In this sense, Ethereum and other similar blockchains can be understood as distributed computing platforms on which applications can be built and run on a global scale. This is made possible by the ability of these blockchains to deploy smart contracts, which can perform complex functions beyond simply transferring tokens between accounts.

With the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) (or its equivalent on other blockchains) providing a general-purpose computing engine to run smart contracts, the digital objects created and controlled by these smart contracts can be designed to be composable. In other words, they can be combined or built upon in different ways to unlock new use cases, much like how developers can leverage application programming interfaces (APIs) to build more powerful software products.

As a result, digital objects on a blockchain not only represent dynamic software, but can also be dynamically connected to other objects or applications on the chain. This composability makes digital items on the blockchain greater than the sum of their parts—building blocks that can generate broader, more engaging, and perhaps even unprecedented digital experiences.

After all, the components of digital culture rarely exist in isolation, even outside of cryptocurrency. A particular cultural item or concept often has staying power in the digital space because it is easily integrated with other elements, or remixed to create derivative works that further draw attention to the original item or concept. In fact, TikTok’s rise as an entertainment platform is attributed to how its tools help streamline the process of remixing videos, effectively turning them into composable media that promotes the network effect of creativity.

Going back to cryptocurrency, I believe that composable digital items on the blockchain can act as cultural amplifiers of digital culture. This is similar to how Licklider once hypothesized that computers could be “intelligence amplifiers” by enabling new ways of thinking, such as what computer scientist Alan Kay described as “through dynamic simulation.” In this regard, on-chain composability can enhance the remixing process for creators and consumers, while catalyzing new ways of creating digital culture.

On one hand, blockchain allows for more robust tracking of connections between digital items on the blockchain, which can help facilitate attribution and other licensing arrangements (such as Story Protocol and Overpass). This will also support the monetization of derivative works, ensuring that original and secondary creators are properly compensated.

In addition to these practical benefits, on-chain composability can open up new horizons for artistic works or cultural experiences. While we have only seen the initial results of this effort, I hope that this feature of the blockchain can become a ground zero for creativity in digital culture.

Located in the "Arc" region {17, 41} at level 13, biome 36"

Located in the "Arc" region {17, 41} at level 13, biome 36"

Terraforms (2021) is an on-chain art project by Mathcastles that seeks to leverage the unique computational advantages of blockchain to create artworks that cannot be realized elsewhere.

On the surface, Terraforms consists of nearly 10,000 on-chain animated plots of land on the Ethereum blockchain, which together form a 3D world known as "Hypercastle." But its core artistic concept—distributed computing as an art form—is expressed through its underlying technical infrastructure. As software engineer Michael Yuan explains in a post about Terraforms, As brilliantly described in the article by , it consists of a set of smart contracts that store raw data for parcels, define the structural parameters of the Hypercastle, generate noise to add a natural feel to the rendering, and generate parcels at runtime.

The technical infrastructure supports composability on multiple levels. The raw data contracts can support other on-chain applications. The rendering contracts allow for multiple independent versions of the Hypercastle to be generated (multiverses!), while the NFTs provide a canonical version of the hyperstructure for owners and the wider community to build tools around. The antenna mode introduced during the recent v2 upgrade will also allow parcels to receive "broadcasts" from other smart contracts (yet to be released), providing another way for interested parties to continuously reshape the Hypercastle terrain.

9 in the "Dhampir" region {6, 3}

9 in the "Dhampir" region {6, 3}

To fully present Terraforms as a complex and multi-dimensional work of art would probably require a separate article (see Malte Rauch’s excellent review of Terraforms on glitch Gallery). But I highlight it here as an example of how on-chain artworks can take full advantage of composability through their technical infrastructure to propose an aesthetic vision that is both ambitious and open-ended. As Terraforms becomes a classic work of on-chain art, it may well become a gathering point for other artists and cultural stakeholders to explore new and imaginative possibilities with distributed computing as a medium for the expression of ideas and creativity.

Networked Digital Objects as Coordination Hubs

Like the expansion of the wider Internet, blockchains need network effects to grow and thrive. They are essentially networked communication devices with a common economic base. So, regardless of technical capabilities, the more people use a blockchain, the more attention and liquidity it will have, and therefore the more cultural creativity it will foster.

As distributed computers, blockchains enable not only on-chain composability but also on-chain network effects. Digital cultural objects on blockchains should take advantage of both to maximize their potential as cultural amplifiers. Large networks offer vast possibilities for composability to work its magic.

Furthermore, value will accrue primarily at the network level rather than at the object level, as it becomes cheaper to create digital content using generative AI, link them to the chain using layer-2 blockchains (L2), and distribute them to audiences across multiple digital environments via decentralized social media. This is the premise of Chris F’s “token constellation theory”, part of his Starholder world-building project. The theory argues that we may increasingly view digital objects on blockchains as constellations of digital tokens, not as individual tokens, but as experiences as a whole.

These composable and networked digital objects will generate coordinated demands to attract and direct the flow of value across the collective. In such a “complex adaptive media system”, network participants will inevitably try to self-organize and exert their own agency within it. This adds a new dimension to digital cultural objects on the blockchain. They are no longer seen simply as distributed, ownable objects, used to transmit or trade their cultural value, but as networked objects with their own emergent behaviors and cultural spheres of influence—they are agents of an unwritten, open multiplayer game on a distributed computer.

The idea that networked digital objects can serve as coordination centers for digital culture has been most widely experimented and popularized by decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs). However, it remains to be seen whether this structure is an effective coordination platform that can bring value to networked digital object collections or the wider space.

Nouns has pioneered a unique fundraising and distribution mechanism in which an on-chain digital avatar (called a Noun) is generated and auctioned once a day. The winning bid then goes into the Nouns DAO’s treasury, which is composed of the owners of each Noun, who can make suggestions and vote on how the treasury funds should be spent.

Nouns has pioneered a unique fundraising and distribution mechanism in which an on-chain digital avatar (called a Noun) is generated and auctioned once a day. The winning bid then goes into the Nouns DAO’s treasury, which is composed of the owners of each Noun, who can make suggestions and vote on how the treasury funds should be spent. To date, the DAO has primarily funded initiatives to promote the Nouns brand, such as the production of a Nouns-themed film, and for charitable causes, such as funding and distributing glasses to children in need.

However, the decentralized governance process within the Nouns DAO has not been without controversy, with some arguing that the DAO was wasting funds on lavish initiatives.In September 2023, a subset of Nouns owners voted to take their Nouns out of the DAO and create a "forked" DAO based on their pro-rata share of the original DAO's treasury. The owners of the forked DAO could then exit and claim their underlying assets. At the time of this fork, the Nouns DAO lost more than $50 million in funds. Many of the Nouns that left the original DAO were said to be owned by arbitrageurs who bought them at less than "book value" and used the fork to redeem them at a higher price. Since then, Nouns DAO has forked two more times, in October and November 2023, demonstrating the significant difficulties in reaching consensus on the purpose of collections of digital objects.

Artists have also exploited the networking possibilities of blockchain as part of their artworks. They can deliberately incorporate coordination mechanisms into their artworks or allow collectors to participate in their own way, which shows the permissionless nature of this space.

In any case, the intentional or spontaneous coordination behaviors around these artworks do place them within the broader artistic tradition of performance art and participatory art, allowing artists to participate in the social reality of cultural activities on the blockchain in a direct and medium-specific way.

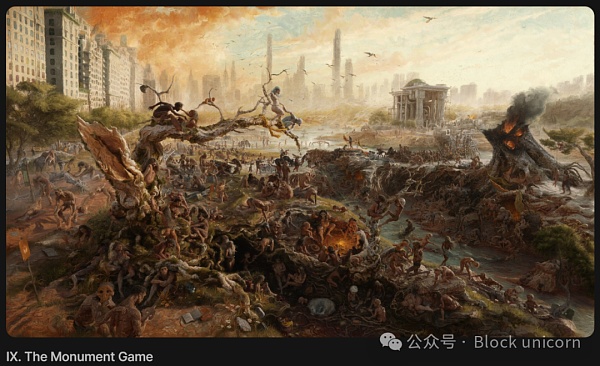

In August 2023, digital artist Sam Spratt released The Monument Game on Nifty Gateway, an artwork centered around an epic 1/1 digital painting, in which 256 “players” who hold another limited edition work by the artist are invited to record their observations at specific locations in the painting. The artwork builds on the artist’s previous deep knowledge base in digital painting, but also gives “players” enough space to add a final layer of color to the work and the world it represents - or in Sam Spratt’s own words, “add a little bit of themselves to the work and the world it represents”.

The Luci Committee - a cadre of art collectors and supporters who hold works and tokens of the artist’s “Luci’s Skull” - is voted by players to select the three winning observations. The three winning players are then offered the opportunity to join the committee by sacrificing their limited edition “Player” piece in exchange for the “Skull of Lucy.”

The beauty of the entire artwork comes not only from the evocative painting itself, but also from the multiple connections it makes to the wider universe created by Sam Spratt. These observations connect each player to their collected version, which in turn is permanently inscribed on the canvas. The participation of the “Skull of Lucy,” a derivative artwork originally awarded to the sole bidder for an earlier artwork by the artist, further connects this artwork to the dynamics of the past, allowing history to inform the present and thus influence the future. The Monument Game as a whole is a complex system where story, community, and game are carefully woven together on the blockchain.

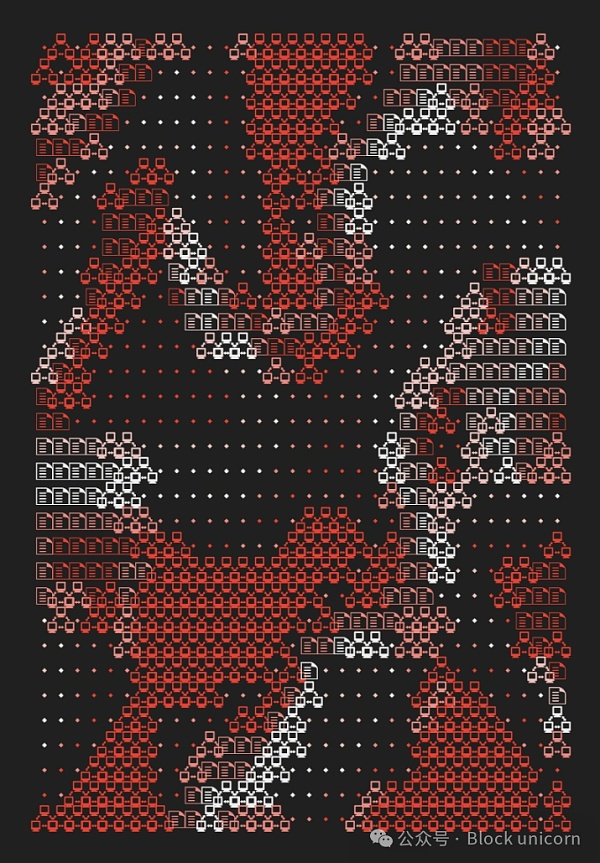

MUTATIO is a collaborative work by two anonymous artists XCOPY and NeonGlitch86, an open edition work released on Base L2 in March 2024, priced at a few dollars in ETH per edition. In 24 hours, more than 1 million editions were minted from more than 30,000 unique blockchain addresses.

Many are obviously speculating that the artist may introduce more uses for each edition, perhaps burning them to unlock new artworks or experiences. Nonetheless, the combination of low minting prices and a large number of editions may be fertile ground for experimentation with new blockchain mechanisms. Some have already created fungible tokens ($FLIES) backed by MUTATIO versions, allowing artworks to be explored and more easily traded through DeFi infrastructure. For me, MUTATIO brings to life the idea that networked digital objects can be places of coordination, and foreshadows a future where artists become “magicians of the crowd” – managing networked objects, tokens, texts, memes, ideas, capital, and more.

Finally, we cannot escape the fact that by far the most popular use case for blockchain is the “casino”.

Financialization of Culture

As always-on, always-accessible computers that anyone can create on the blockchain, the blockchain has proven to be an ideal place to attract speculative capital. Here, there are almost no barriers to stop the flow of money – pursuing new heights, chasing returns, and sowing the hope of immeasurable wealth. Since the threshold for creating any token is relatively low, the supply side is also met. Anyone can create a new token or a new digital object with relative ease, and then attract the arrival of huge liquidity.

In the frenzy of the NFT market in 2021-2022, we have witnessed the rampant financialization of almost all digital content through NFTs, ranging from fine art to all kinds of digital collectibles and paraphernalia, such as old tweets, selfies, and even recordings of your own farts.

While demand for these NFTs has plummeted almost as fast as it has grown, it is clear that cryptocurrencies have made the cultural and financial spheres more closely intertwined than before. For the first time in the short history of the Internet, we can now create digital items and have an open and unstoppable market for these assets.

If you don’t like gambling, then this hyper-financialization of digital culture is off-putting because it creates a lot of distorting effects in how valuations are done. For example, hype influencers may artificially drive up the price of their target NFT or ordinals and then exit at a profit later, to the detriment of existing collectors.

However, we should also recognize that culture has always been financialized, as is evident from the gold-mining business in online games or the way parts of the contemporary art world operate. Cryptocurrency simply makes the underlying relationship between culture and money more obvious, and in a sense more honest. For those who want to make a quick buck, there’s no need to pretend. Nor can they do these things in a sneaky way, since all their on-chain transactions can be publicly tracked.

By having information about past transactions on the blockchain, we can also form our own independent conclusions about how specific cultural assets should be priced. It’s like playing a game in a casino, where the past data of each game, such as the odds of winning, is available to all players. At the very least, we can take the necessary precautions when trading digital cultural items on the blockchain, or just keep our eyes open. For me, this is a much better way to navigate the digital art and culture market, even if I have to take on gamblers and charlatans along the way.

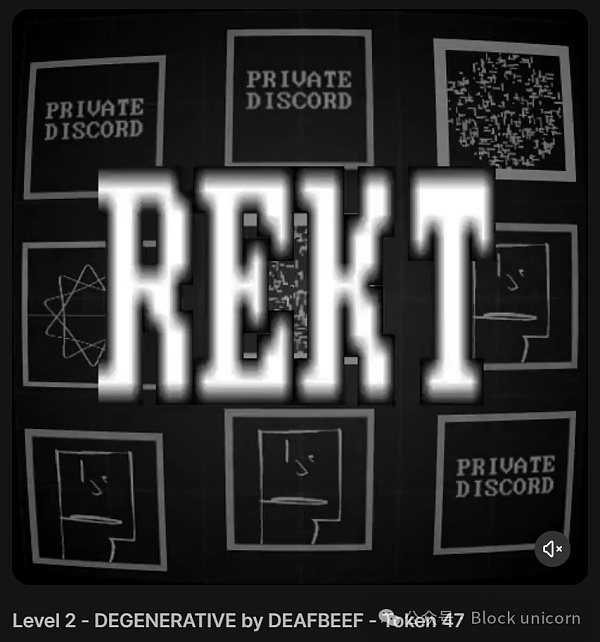

0xDEAFBEEF’s Degenerative (2021) is a slot machine game implemented on the Ethereum blockchain. The series begins with a set of pre-minted Level 0 machines as NFTs, whose owners can submit transactions on the associated smart contract to gamble and try to win the jackpot. Doing so will grant them a minting pass to mint an additional slot machine at the next incremental level. Slots at higher levels have lower odds of winning the jackpot, while also having a lower supply cap. As of the time of writing, the Level 2 slot (token 47) shown above has won the most jackpots (6 times) in the entire series. This was achieved with 40 rolls, for a 15% chance of winning, significantly higher than the 3.5% jackpot probability specified for that level.

The work was created at the height of the market in 2021, in the context of the collision between generative art and cryptoeconomics. At the time, many speculators, under the guise of appreciating art, actually treated generative artworks as playing cards, exploiting their properties to profit from the market. In the artist’s own words, Degenerative seeks to pose a real question to creators and collectors about their motivations for engaging with the generative art field at that particular point in time: “What did that moment represent: a revolutionary paradigm in digital art patronage? A one-off opportunity to compete for scarce resources? A pointless, frantic expenditure of time and energy? Was it a rational decision in uncertain times?”

From ‘Casinos’ to IntegratedResorts

In Singapore, our casinos are part of larger mixed-use developments called ‘Integrated Resorts’. The idea behind such resorts, which combine leisure, entertainment and commercial functions, is that the casino component will help make the entire development financially viable by subsidising other components such as hotels, retail, conference spaces, theatres etc.

This is not a novel concept. Other casino developments around the world have taken a similar approach by expanding their appeal beyond gambling to attract more people. The evolution of Las Vegas itself is a testament to this – its once mafia-run casinos have morphed into professionally managed and family-friendly mega-resorts, now world-renowned for their rich and varied entertainment options and high-quality recreational facilities.

I think there is a parallel evolution happening in the crypto space. There are now many more ways to participate in crypto culture than just being a gambler and joining discussions about making money. Today, people can create, curate, and collect quality digital art on the blockchain; interact with others through decentralized social media protocols like Farcaster, and use consumer applications for a variety of blockchain-related uses, such as for ticketing, membership, and loyalty programs. Many of the applications that support such functionality are also funded through the wealth effect generated by crypto casinos - directly or indirectly.

In fact, as Bradley Freeman, product marketing manager at Stack, observes on the consumer crypto side, "on-chain resorts are being built on top of on-chain casinos." He also points out that both casinos and resorts have a symbiotic relationship, which is evident in the ecosystem that memecoins are creating.

For example, the memecoin ($DEGEN) built on Base L2 can be seen as a cryptocurrency that bridges two different worlds - as a cryptocurrency for speculators to bet on the success of Base L2 and/or the Farcaster protocol de1, but also as an incentive to build other use cases both within and on top of both ecosystems. $DEGEN has a unique distribution mechanism centered around eligible users tipping other users on Farcaster. While there are certainly users trying to game the distribution mechanism to get more $DEGEN tips, it’s exciting to see this meme coin being used for positive-sum games, such as supporting artists, writers, and anyone who is making meaningful contributions to the space. It’s also being used to power other applications, such as $DEGEN, which has become the native token of its own blockchain, Degen Chain, and is used to incentivize content creation on Drakula, which aims to be a blockchain-based alternative to TikTok.

$DEGEN only launched in January 2024 and is still in its early stages. But its success to date hints at the potential for a sustainable consumer crypto ecosystem alongside crypto casinos. With the foundations of on-chain integrated resorts being laid today, we can look to the future to bring or cultivate popular culture on the blockchain.

Poroscity (2023) is a video artwork produced by Niceaunties using AI tools, launched as part of a four-part series during the Artists Daily Show on Fellowship’s daily.xyz platform on November 30, 2023. The video showcases Auntiverse City, a dreamlike, surreal urban environment characterized by its vibrant, organic architecture and colorful inhabitants, including aunties who are living their best lives.

Auntiverse City reflects the artist’s vision of a physical city: colorful, fun, and vibrant. Similarly, our on-chain integrated resorts and cities should be places where we can freely enjoy ourselves with our friends and do fun and meaningful things.

I spent some time elaborating on my mental model of the five “Cs” to show that blockchain already provides a fairly powerful toolkit for producing and consuming digital culture.

Going back to what I wrote at the beginning, we can think of crypto as an open, free workshop. Here we can use multiple types of tools to foster more durable and vibrant forms of digital culture, even in their inherent transience and volatility.

The main types of tools in the crypto workshop are summarized below:

Records: These historical records are open, verifiable, and interoperable, helping us map and navigate the evolving and expanding landscape of digital culture.

Custodians: Custodians enable us to take ownership of digital objects, encouraging us to become stewards of these objects and of digital culture more broadly.

Canvas: Canvas is where we can create living and persistent digital objects, providing novel digital experiences that are interactive, engaging, and memorable.

Computers:Computers provide a medium for digital objects to be more efficiently combined and networked, thus opening up new areas for the development of digital culture and unlocking new possibilities for co-engagement with it.

“Casinos”:Financialize and fund digital culture by providing a channel for speculation to become investment, which will be used to build a broader and sustainable cultural ecosystem on the chain.

To wrap up this post, I updated my concept map to include some keywords. If you are interested in the framework of the five “Cs” in this post, you can cast the original concept map for free on Zora.

Of course, how we use these tools is a personal prerogative. The blockchain itself cannot force us to act in a particular way. Instead, it is up to us to decide how to use the unique conveniences that blockchain enables.

So in this post, I’m not trying to describe what I think is good culture and what I think is bad culture. There’s no point in being a cultural purist, because the radical openness of the internet and public blockchains naturally brings chaos. That’s who we are as humans — full of contradictions and tensions, but full of possibilities and potential. When we have the freedom to create, we can create endless garbage as well as eternal holy grails. We love to destroy things, but we also love to build things. We crave conflict, but we crave community. We think in terms of singularities, and we embrace the multitude at the same time.

Being on-chain doesn’t change this off-chain nature. So when cryptocurrencies offer an open, free workshop and a lot of shiny tools, we do what we always do. We rush in and play with them intuitively. In the process, we mess up the tools. We make a lot of noise and demand that others use the tools our way. We also curate and manipulate so that the tools are for our own benefit and not for the benefit of others.

But amid the noise, we also realize that these tools in the crypto workshop can be used to create beauty, no different than other tools we’ve become familiar with. As a result, some of us notice an equally primal but perhaps more subtle call — to try to carve out a space to tinker, hone our craft, and create cultural objects with these tools that make us feel. In the process, we try to organize and inspire those around us through the vision and values around this new toolkit. In the face of the finiteness of life, we continue to use all these available tools to reach for the infinite. Ultimately, we all fail and die, but in this effort, we do our best to create something that will outlive us.

The sum of all these activities is what I understand as culture — using tools to create something that will live on. In the context of the internet, cryptocurrencies give us a novel and unprecedented toolkit to do just that.

With the 5 Cs, we now have the ability to build hyperstructured platforms that, in the words of Zora co-founder Jacob Horne, “run for free and forever, without maintenance, disruption, or intermediaries.” On these hyperstructures, we can in turn freely grasp and trade hyperobjects, and unstoppably, through which we can assemble the raw materials necessary to create meaning that will hopefully persist in the hyperreality of the digital age we inhabit.

At the same time, we must also be realistic. Whether we view the internet as a homogenized, algorithmically driven “filtered world” or a terrifying, silencing “dark forest,” most of what we will create will never see the light of day, even if created on a blockchain. But blockchains at least allow us to set a signpost so that like-minded people may one day glimpse it—hear the faint echo of a fallen tree in a forest that was inhabited many generations ago.

In this sense, digital culture on blockchains is always active. May it survive and never die.

The crypto data platform plans to integrate new endpoints into its crypto data API by Q2 2024, covering various aspects of NFT data across major platforms.

Davin

DavinHe explains that the rise of generative AI is just another way for digital companies to profit from the creative work of others

Bitcoinist

BitcoinistChatGPT is the latest step towards a world of infinite, customizable content, all generated by artificial intelligence.

The Generalist

The GeneralistThis comes after the collapse of hedge fund Three Arrows Capital and crypto exchange FTX.

Beincrypto

BeincryptoDominica is the current frontrunner; Justin Sun wants a crypto-friendly environment.

Beincrypto

BeincryptoReuters have written a crypto-gossip piece on Changpeng Zhao and Binance

Beincrypto

BeincryptoChina banned crypto trading and mining last year.

Coindesk

CoindeskAs the bears continue to reign the crypto markets, we caught up with Cosmin Mesenschi, the founder and CEO of ...

Bitcoinist

BitcoinistMEXC Global, a leading digital asset and cryptocurrency trading platform, has today announced a partnership with the Pyth Network, an ...

Bitcoinist

BitcoinistAustralian basketball media company, Basketball Forever is using NFTs to massively increase fan engagement.

Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph