Charles Shen @inWeb3.com, author

Leia @TEDAO, compiler

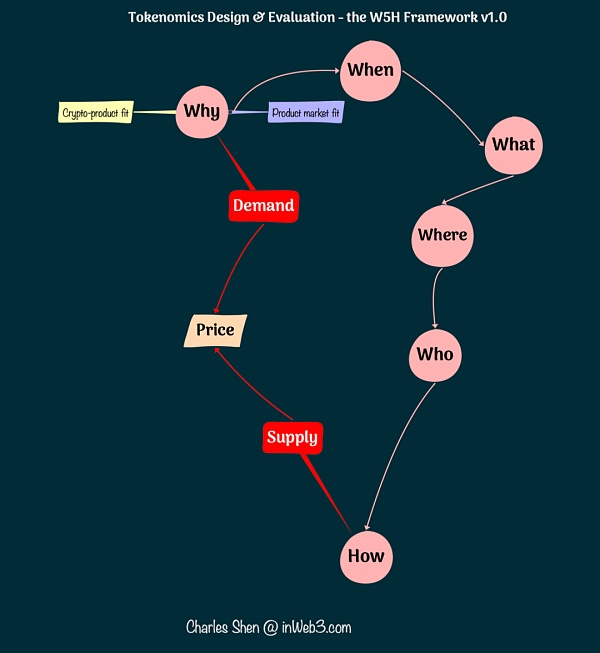

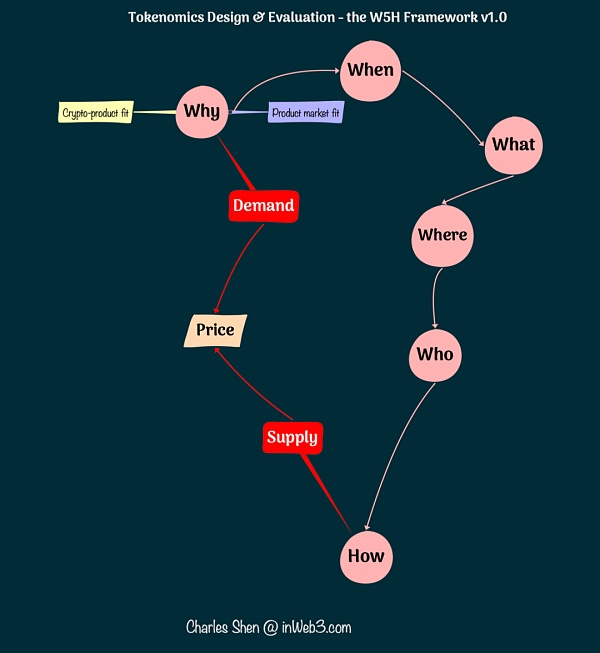

In the first article of "Basics of Token Economics Series - W5H Token Design Framework", we explored "Why: Why do we need tokens?" from the perspective of crypto-product-market fit, focusing on the role of crypto tokens in the business and whether they can create sustainable economic value, which helps us determine whether a project needs its own token.

W5H Token Design Framework (Why)

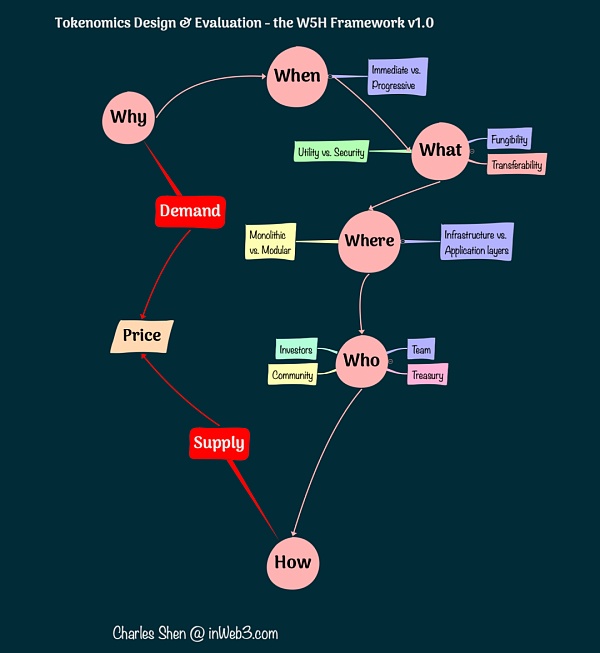

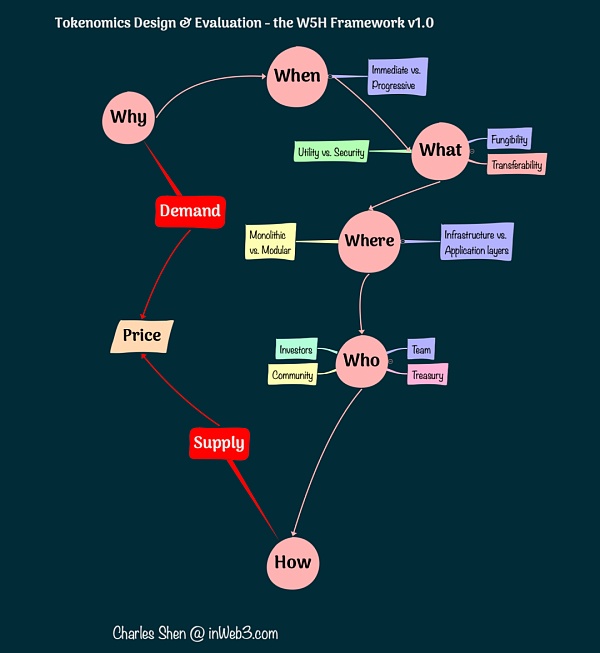

In this article, we continue to explore the other 4 "Ws", namely "When, What, Where, Who".

W5H Token Design Framework (W5)

When: When to issue tokens?

If the demand for tokens is justified, we need to ask — when is the best time to issue a token? For tokens with specific utility, a rule of thumb is — when the utility is essential to the crypto project, the token should be issued.

If the crypto project is tokenizing assets directly (such as the B-type products discussed in Part I), then the tokens themselves can drive the product launch. For example, a stablecoin pegged to the value of one dollar in fiat currency, a token representing carbon credits, an NFT of a specific artwork, or an NFT that serves as a membership certificate for a social club.

When the token is used as an incentive for large-scale decentralized coordination (such as the C-type products discussed in Part I), we need to delve into the specific goal that the token is incentivizing. If the goal is essential to the current stage of the product launch, the token should be issued along with the product. A typical example is a token used to maintain the security of the product. In the case of proof-of-stake (PoS) blockchains, where tokens are used as validator stake to secure the chain, issuing tokens in sync with the product is a must. Similarly, tokens that maintain critical security status at the application level (e.g., to ensure the safety module functionality in AAVE) can also justify issuing tokens with the product. Note that the cases discussed here assume that the project uses its own token to achieve security goals. Projects can also consider other solutions, such as EigenLayer, which allows new crypto projects to commandeer existing ETH stakers on the Ethereum blockchain to reuse these staked ETH to ensure the security of new projects.

If the purpose of the token is not part of the core business logic - at least for now - then the timing of token issuance needs to be carefully considered. A typical example of such a token is a governance token, which is used to encourage community participation and provide decentralized ownership. This situation may apply whether the project focuses on dealing with other crypto assets, asset tokenization, or large-scale decentralized autonomous coordination (i.e., the A, B, C products defined in the first part).

On the one hand, the fundamental proposition of the Web3 vision is to create an "ownership economy" that enables the user community to manage and benefit from the platform that provides services. Issuing tokens is an important way to achieve this goal. Li Jin, co-founder of Variant, found that "On average, Web3 companies that issued tokens did so 2.7 years after their founding; in contrast, in 2020, venture-backed companies chose to go public on average about 5.3 years after receiving their first venture capital. The timeline of IPOs, compared with token issuance, may cause ordinary investors to miss out on a lot of potential returns."

On the other hand, although fully decentralized governance is very attractive for Web3 projects, it is often not necessarily the best choice in the initial stages of many projects. Most projects are started by a small number of core members. They build crypto products and cultivate active communities. Agile teams iterate quickly and strive to find product-market fit. When the product is proven and the community is growing, the demand may begin to exceed the capabilities of the core team. At this point, the team can gradually transfer ownership to an engaged community through tokenization and use the power of the community to promote the future development of the project. This process is called "progressive decentralization" in the crypto space. There are many examples of such crypto projects. Uniswap was founded in November 2018, but did not launch its governance token until September 2020. BAYC started with a highly successful NFT launch in April 2021, and a year later, it went on to launch a governance token in April 2022.

It is also worth noting that not issuing tokens at the launch of the project does not mean sacrificing rewards for early community members. Blockchain records can preserve user activity and can be used to identify wallet addresses that have interacted with the project since its inception. It is precisely because of this feature that Uniswap can distribute 15% of the total supply of $UNI to early users even though it did not issue tokens until nearly two years after launching the service. BAYC will also airdrop 15% of ApeCoin directly to existing users who hold BAYC and MAYC NFTs.

What: What type of tokens to issue?

If the timing of issuing tokens is determined, we need to further consider the specific type of token. There are many ways to classify tokens, depending on their different properties. We discuss a few major categories here:

Fungibility:An important feature of a token is whether it is fungible or not. Fungible tokens can be exchanged for each other. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have unique properties that cause them to have different values. Both types are common and each has its own meaning. The choice between the two depends on the use. Here are a few examples:

Tokens that act as money are inherently fungible. Bitcoin and Ethereum are both fungible tokens.

Governance tokens are often fungible. For example, $UNI is the governance token for Uniswap. The BAYC community started out as an NFT project and later issued a fungible token, ApeCoin, for governance.

Tokens that act as “gatekeeping” are often non-fungible because they represent a ticket to a specific event or to join a club. The BAYC NFT is an access ticket to the Bored Ape Yacht Club. But not all access tickets need to be NFTs. Friend with Benefits is another social club that uses a certain amount of a fungible token, $FWB, to control eligibility.

Tokens that allow participation and rewards can be either fungible or non-fungible. Filecoin’s “work-to-earn” model allows operators to provide file storage services by staking a fungible token, $FIL. Meanwhile, the Axie Infinity game requires users to own Axie NFTs to participate in the game and join the play-to-earn model. Tokens used as collateral for lending can be fungible or non-fungible, as long as the underlying token assets are considered valuable. Ethereum and Bitcoin are fungible tokens that can be used as collateral assets. And blue chip NFTs, such as Cryptopunks, can also be used to lend assets.

While the above list shows that both fungible and non-fungible tokens can be used in most cases, there are still a few rules of thumb to refer to:

When both token quantity and interchangeability are important, fungible tokens are preferred.

Cryptocurrencies used as payments naturally fall into this category. Many work-to-earn models that provide general services also fit this category, as staking more tokens may reasonably lead to higher return opportunities.

The situation with governance tokens is slightly more complicated. The number of governance tokens provides a way to differentiate governance weight. However, interchangeability is not always a desirable feature of governance tokens, as sometimes we may not want governance rights to be exchanged between unrelated people.

NFTs emphasize their unique properties or utility, not necessarily the relative number of tokens, such as BAYC-like tokens as tickets or collectibles such as Cryptopunks. However, if necessary, differentiation in quantity can still be achieved by using multiple NFTs.

Transferability vs. Non-Transferability: In most cases, token holders can transfer their tokens to other wallets or transfer them to other people at any time. These tokens are transferable. But there are cases where token transferability may be prohibited. Ethereum co-founder Vitalik calls these non-transferable tokens soulbound tokens. The best example that fits this category is POAP, which stands for "proof of attendance protocol." POAPs are NFTs that prove that the recipient was physically present at certain events. If POAPs were easily transferable, people could obtain them without actually attending the event, and the token would lose its meaning. Another type of token that might need to be non-transferable is governance tokens. When governance rights need to be limited to a certain group of people, prohibiting the transfer of tokens prevents unauthorized people from obtaining these tokens.

Security Tokens vs. Utility Tokens: Whether a token is a security has important legal implications for the token issuer. While many tokens can be considered commodities with some utility, other tokens may function as securities. For example, they may represent an ownership investment in a company, similar to traditional financial securities, and therefore may be subject to similar securities regulations. A well-known method for determining whether a token is a security is the Howey Test. It contains four main criteria: "investment of money, participation in a common undertaking, expectation of profit, and profit derived from the efforts of others." The Crypto Ratings Council (CRC) is an organization that evaluates many major crypto tokens and rates their likelihood of being classified as securities.

Where: At which layer of the blockchain network should the token exist?

The question of "Where" leads us to continue to explore at which layer of the blockchain network stack the token should be deployed.

Tokens can be divided into infrastructure-level tokens and application-level tokens. Infrastructure-level tokens are components of the corresponding blockchain itself. Such tokens usually play a key role in ensuring the security of the blockchain and are often used as the native settlement currency on the blockchain. As the industry develops, blockchain infrastructure has also been subdivided into so-called Layer 0, Layer 1, and Layer 2. Accordingly, people have begun to call blockchain applications built on top of the infrastructure Layer 3.

The most famous infrastructure-level tokens are $BTC for the Bitcoin blockchain and $ETH for the Ethereum blockchain. Other examples include $BNB on Binance Smart Chain, $AVAX on Avalanche blockchain, $SOL on Solana blockchain, and $ADA on Cardano blockchain. They are all Layer 1 blockchains.

Layer 2 blockchains were created in response to the "scalability trilemma". This dilemma states that using "simple" technology, only two of the three properties of scalability, decentralization, and security can be met. Layer 1 blockchains that can provide high security and decentralization may have to sacrifice scalability. Layer 2 emerged to improve the scalability of Layer 1, and they usually inherit the security of their corresponding L1 blockchain. Therefore, from the perspective of ensuring economic security, Layer 2 may not need its own token. But they can still issue tokens, for example for incentives. These Layer 2 tokens can also be considered infrastructure-level tokens because they are part of the environment in which the application is deployed. Among the many well-known Layer 2 solutions on Ethereum Layer 1, Polygon has its token $MATIC (originally used for the Polygon Ethereum sidechain), and Optimism has issued its OP token. As of the end of 2022, other Layer 2 players such as Arbitrum, zkSync, and starkNet have not issued their own tokens.

Layer 0 blockchain refers to a group of crypto projects that focus on providing interoperability between various blockchains. Polkadot and Cosmos are two typical examples, and $DOT and $ATOM are their infrastructure-level tokens.

Where the token is issued depends on the nature of the crypto project. If it is an infrastructure project, it can build its own Layer 0, Layer 1, or Layer 2 blockchain. Most crypto projects for Layer 3 applications can deploy their application-level tokens directly on existing Layer 1 or Layer 2 blockchains. The underlying blockchain usually provides specific workflows to simplify the issuance of these tokens. For example, Ethereum has standards for creating fungible tokens (ERC20) and non-fungible tokens (ERC721), as well as an updated standard (ERC1155) that supports both fungible and non-fungible tokens. Tokens based on these standards can be immediately interoperable throughout the Ethereum ecosystem.

It is worth mentioning that there is currently a very heated discussion about monolithic blockchains and modular blockchains. This discussion looks at the problem from a different perspective and divides the blockchain system into several component layers: execution layer (acting on smart contracts and processing transactions), settlement layer (verifying transaction validity and making final settlement), consensus layer (keeping transactions in order), and data availability layer (ensuring that all nodes can obtain all transaction data in the block). Most mainstream blockchains such as Bitcoin and Ethereum are monolithic blockchains that integrate all these component layers. Layer 2 can be regarded as a modular execution layer. Ethereum has formed a partially modular structure on Layer 2, which has improved scalability compared to the original monolithic chain. Ethereum is also building a sharding expansion solution that supports higher data availability throughput - danksharding. In addition, there are projects that are building independent modular data availability layers and consensus layers, such as Celestia, Polygon Avail, and EigenDA, which do not have an execution layer. The development of modular blockchain layers has spawned a growing interest in building application chains (AppChains).

The application chain approach gives application technology sovereignty, allowing applications to customize different layers of their blockchain stack to improve performance and value capture. There are already several infrastructures that can be used to support the construction of AppChains, such as Cosmos Zones, Polkadot Parachains, Polygon Supernet, and Avalanche Subnet. Appchain tokens can be used for staking and verification on their networks and for application-specific purposes. However, the AppChain paradigm also has limitations, such as reduced composability and decentralized liquidity due to the need for additional cross-chain bridge infrastructure, as well as increased friction and security risks. Axie Infinity implemented its Ronin AppChain as an Ethereum sidechain to cope with the explosive growth in transaction throughput requirements for games. However, in March 2022, it suffered a hacker attack that cost it $622 million.

In addition to cross-chain bridge risks, if AppChain only uses its application tokens as collateral to ensure the security of the chain, the security of AppChain itself is also vulnerable. To alleviate the problem of AppChain economic security, one trend is to leverage shared security mechanisms from more mature infrastructures, such as Cosmos' ICS shared security (interchain security) and Eigenlayer's ETH re-staking mechanism.

Overall, most applications are still more likely to be issued on Layer 1 and Layer 2, while AppChains are more suitable for certain types of applications that have already reached considerable scale, achieved product-market fit, and are expected to benefit significantly from a dedicated blockchain stack, and such applications have relatively fewer constraints on security and atomicity. Several high-profile projects are actively exploring their AppChains strategies. dYdX, which originally ran on Ethereum Layer 2, has announced that it will build its dYdX chain on Cosmos. The team hopes that this move will take advantage of the "unique combination of decentralization, scalability, and customizability" of the potential dYdX AppChain. The proposal for Uniswap to build its AppChain has also sparked some debate.

Who: Which participants should hold the token?

The "Who" question explores the target stakeholders of the token (which participants should hold the token). Tokens are a tool that aligns the interests of all parties interacting with the relevant crypto-economy. We want parties that create value and help the economy grow to own and hold tokens. Usually, when we discuss the question “Why do we need tokens?”, we should already have a list of potential ecosystem participants when we discuss the issue from the perspective of crypto token-product-market fit.

Many projects will clearly allocate tokens to the following three types of participants:

Team:Team members may include core developers, operations staff, marketing staff, consultants, etc. They invest time to build the product.

Investors:Investors include private and public investors. Private venture capital is an important source of funds for crypto projects.

Community:The community of a crypto project includes various different participants. We can segment them in different ways to better meet the needs of project development.

Role-based:Community members can play different roles. For example, in a two-sided market business model, there are community members who are suppliers and other members who are end users. In a market like In a decentralized exchange like Curve Finance, the supply side is the liquidity provider, and the end user is the person who exchanges crypto assets on the exchange. Liquidity providers are critical to ensuring low slippage exchange services.

Time-based:If a project has already established an existing community before issuing a token, it is common practice to reward these early users who support the project separately. As the project grows, rewarding current and future users becomes more important, so users who continue to participate in the project are another important category. For example, Stepn is a Web3 lifestyle app that combines elements of SocialFi and GameFi. It rewards users for walking, jogging, or running outdoors and allocates 30% of the total token supply for such activities.

Contribution-based:The project may also identify users who contribute the most to the ecosystem, and the measurement criteria depends on the specific application scenario. Bankless is a DAO dedicated to the creation of media content and aims to be a leader in the decentralized Web3 vision. They reward participants for their contributions with $BANK, which also becomes their access credentials in the community. In addition, there are DAOs like Rabbithole and Layer3 that specialize in collecting and aggregating token bounties from different DAOs, providing rich contribution opportunities for community members. Contribution-based token rewards are expected to develop further.

In addition to the three types of stakeholders mentioned above, most crypto projects also reserve specific token allocations for the following two purposes:

Project Treasury:Crypto projects usually keep a portion of their own tokens and other crypto assets in their treasury. The treasury is intended to be a reserve fund governed by the community and used to drive the long-term development of the project in the future. This practice is particularly common when the project is decentralized and governed as a DAO.

Ecosystem Incentives:These tokens can also be part of the treasury, but are sometimes explicitly allocated. It can be used to incentivize participants who play an important role in the growth stage of the project. Notable examples include liquidity providers, who provide liquidity to enable other users to trade tokens and other crypto assets with lower slippage, especially in the early stages of token issuance.

Conclusion

This article extends the discussion of "Why: Why do we need tokens?" in Part I to the W5H framework of token design, further covering elements such as "When, What, Where, Who". Since tokens are inseparable from the business and crypto economy behind them, all of these questions should be examined at the business level first and then applied to the token level.

The "Why" covered in Part I looks at the business model and thinks about whether the project solves problems in the real economy or the financial economy. We determine the role of crypto tokens in this business (crypto token-product fit) and how this business can generate sustainable economic value (product-market fit). Based on the specific crypto business model and operating strategy, we can decide whether a token is needed.

If the project does need a token, the "When" step will examine the best time to issue the token. Tokens that are part of the core product must be launched at the same time as the product; tokens that fulfill other independent roles (such as governance tokens) can be launched later if the project wants to adopt a gradual decentralization approach.

The “What” step examines the specific token types. Tokens can be classified along many dimensions. We discuss some of the more important divisions, such as fungible vs. non-fungible tokens, transferable vs. non-transferable tokens, and utility vs. security tokens.

The “Where” step explores the blockchain network stack where the token should be deployed. Depending on whether the token is part of the infrastructure or part of the application, it may be deployed at one of the infrastructure layers (Layer 0, Layer 1, Layer 2) or as an application layer (Layer 3) on top of existing infrastructure layers. We also explore the impact of modular blockchain development and AppChains on token deployment.

The “Who” step examines the ideal categories of key stakeholders (which actors should hold the tokens?). They typically include the development team, community, investors, and project treasury.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance