Source: Financial Times

Jay Powell made clear what he sees as the Fed’s mission as the US economy reels from a severe inflationary shock when he spoke at Jackson Hole last month.

“We will do everything we can to support a strong labour market as we move further towards price stability,” the Fed chairman said at the foothills of the Teton range in Wyoming.

On Wednesday, Powell delivered on his promise, slashing the Fed’s benchmark interest rate by half a percentage point to a range of 4.75 per cent to 5 per cent, kicking off the US central bank’s first easing cycle in more than four years.

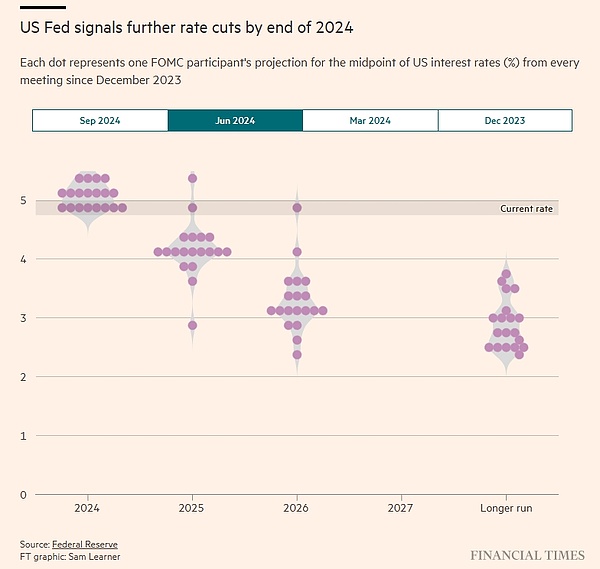

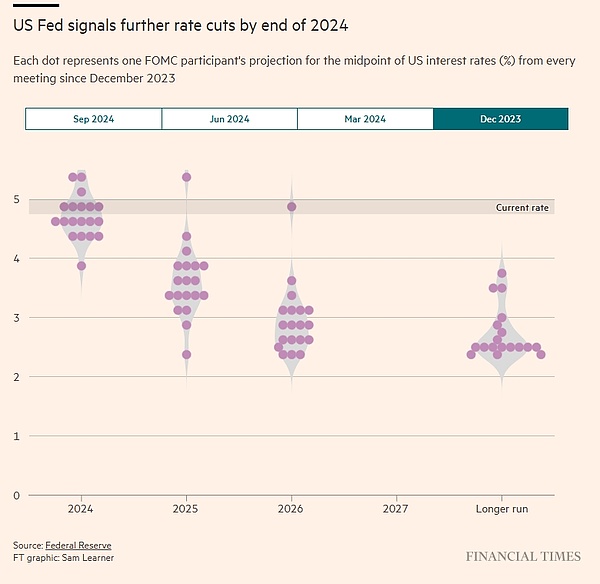

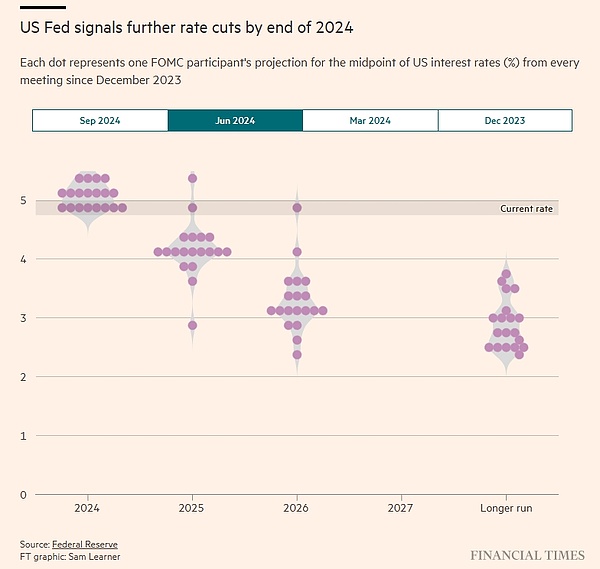

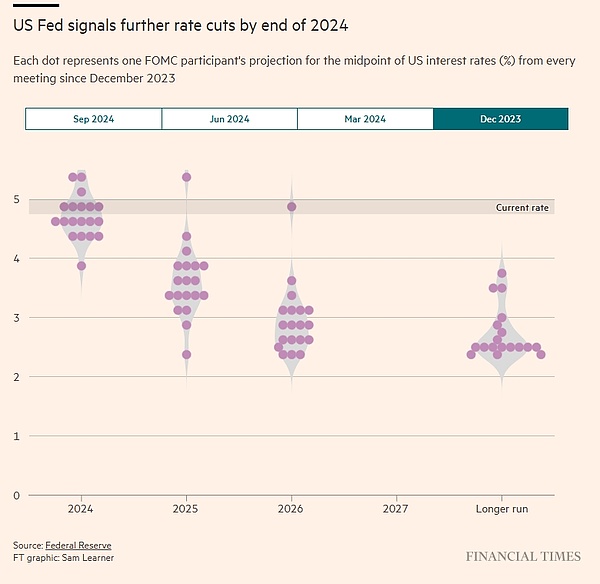

Fed officials also made clear they would not stop there, with the so-called dot plot projections released on Wednesday showing that most members of the Federal Open Market Committee estimated that the policy rate would fall by another half percentage point this year, followed by a series of rate cuts through 2025 to keep rates in a range of 3.25% to 3.5%.

Rather than sparking panic (which many had worried about before the meeting), Wednesday’s half-point rate cut was taken in stride by financial markets, with major equity benchmarks and government bonds ending the day little changed.

“It’s an innovation,” said Peter Hooper, vice chairman of research at Deutsche Bank. “It’s some insurance to prolong the good economic situation.”

“Powell wants to ensure a soft landing,” added Hooper, who has worked at the Fed for nearly 30 years.

The decision is a bold one for the Fed and comes just weeks before the November presidential election, so it has inevitably drawn criticism. Republican candidate Donald Trump has already said the Fed cut rates either for “political” reasons — to help his election opponent Kamala Harris — or because the economy is in “very bad” shape.

In many ways, the decision also marks a watershed moment for Powell, ending a tumultuous period as the world’s most important central banker — a period that has included a global pandemic, the worst economic contraction since the Great Depression, historic government interventions, wars and a severe supply shock that has amplified the worst inflation in 40 years.

Many economists had doubted whether Powell could control price pressures without tipping the world’s largest economy into recession. But inflation has now returned almost to the Fed’s 2% target since it peaked two years ago, while economic growth remains solid.

Explaining the decision on Wednesday, the Fed chairman called the larger-than-usual rate cut a “recalibration” of monetary policy to an economy that is seeing much less price pressure and cooling labor market demand.

“The U.S. economy is in a good place, and our decision today is designed to keep it that way,” Powell told reporters at a press conference after the meeting.

In the past, the Fed has typically deviated from its traditional pace of policy adjustments (i.e., a quarter percentage point) only when faced with a big shock, such as when the coronavirus economic crisis hit, or when the central bank clearly misjudged U.S. inflation problems in 2022.

In the absence of such severe economic or financial stress, the Fed’s big rate cut on Wednesday underscored its desire to avoid an unnecessary recession. If Mr Powell can pull off such a soft landing, it would “stamp” his legacy as Fed chairman, said Diane Swonk of KPMG.

More precisely, Wednesday’s decision reflects the Fed’s efforts to balance risks facing the economy. After getting inflation within its target range, the Fed’s focus has turned to the labour market as slowing monthly growth and rising unemployment have raised concerns.

“The Fed is fully aware that from a risk management perspective, close to neutral is probably the right position given the state of the economy,” said Tiffany Wilding, an economist at Pimco, referring to the level of interest rates that neither accelerates nor depresses growth.

The next step for officials is to calculate how quickly they should cut interest rates to get them to a neutral level. Powell said at a press conference that he was not "in a hurry to get this done." The dot plot also shows that officials are not in agreement not only on this year but also on 2025.

Of the 19 officials who participated in the forecast, two believed that the Fed should keep interest rates at their latest level of 4.75% to 5% until the end of this year. Another seven officials predicted only one more quarter-point rate cut this year. The range of interest rate forecasts for 2025 is even wider.

Powell’s task is to reach a consensus within the FOMC, and at this meeting, Fed Governor Michelle Bowman dissented, voting in favor of cutting interest rates by a quarter percentage point. This made her the first Fed governor to dissent on a rate decision since 2005.

The uncertainty of the economic situation has made it more difficult to reach a consensus. Although the overall situation has improved, inflation remains somewhat sticky, and the once solid labor market has begun to show signs of weakness.

The presidential election is also approaching, although Powell reiterated on Wednesday that the Fed’s decisions will be based solely on economic data.

Jean Boivin, a former deputy governor of the Bank of Canada and now president of the BlackRock Investment Institute, warned that the easing cycle could be “shorter” than financial markets expect.

Traders in the futures market are already pricing in a bigger rate cut than officials have forecast, to a range of 4% to 4.25% by the end of the year, implying another sharp cut at one of the two remaining meetings in 2024. Market participants expect rates to fall below 3% by mid-2025.

“There is a lot of uncertainty about the inflation outlook,” Boivin said, cautioning that the Fed may not offer much relief to borrowers against that backdrop. "I don't think this is the start of an easing cycle. I think it's an easing of tightening."

Weiliang

Weiliang