Article highlights:

CoinDesk found that more than a dozen cryptocurrency companies unknowingly hired IT workers from North Korea, including well-known blockchain projects such as Injective, ZeroLend, Fantom, Sushi, Yearn Finance and Cosmos Hub.

These employees used fake IDs, successfully passed interviews, passed qualification checks, and provided real work experience.

It is illegal to hire North Korean workers in the United States and other countries that have sanctioned North Korea. This also poses security risks. CoinDesk found that several companies were hacked after hiring North Korean IT workers.

"Everyone is trying to screen out these people," said Zaki Manian, a well-known blockchain developer. He said that he accidentally hired two North Korean IT workers in 2021 to help develop the Cosmos Hub blockchain.

In 2023, the cryptocurrency company Truflation was still in its infancy when founder Stefan Rust unknowingly hired his first North Korean employee.

“We’re always looking for great developers,” Rust said from his home in Switzerland. Unexpectedly, “this developer met us.”

“Ryuhei” sent his resume over Telegram, claiming to be working in Japan. Soon after he was hired, strange inconsistencies began to surface.

At one point, “I was on the phone with the guy, and he said he had an earthquake,” Rust recalled. But there hadn’t been an earthquake in Japan recently. Then the employee started missing calls, and when he showed up, “it wasn’t him,” Rust said. “It was someone else.” Whoever it was had dropped the Japanese accent.

Rust soon learned that “Ryuhei” and four other employees, more than a third of his team, were North Korean. Rust had inadvertently fallen for an organized North Korean scheme to give its employees remote overseas jobs and send the earnings back to Pyongyang.

U.S. authorities have recently stepped up warnings that North Korean IT workers are infiltrating tech companies, including cryptocurrency employers, and using the proceeds to fund the country’s nuclear weapons program. According to a 2024 United Nations report, these IT workers earn North Korea up to $600 million per year.

Hiring and paying workers — even unintentionally — violates United Nations sanctions and is illegal in the United States and many other countries. It also poses a serious security risk, as North Korean hackers have been known to target companies by secretly hiring them.

A CoinDesk investigation reveals how aggressively and frequently North Korean job seekers target cryptocurrency companies — successfully interviewing, passing background checks, and even showing an impressive history of code contributions on the open-source software repository GitHub.

CoinDesk spoke to more than a dozen cryptocurrency companies that said they had inadvertently hired IT workers from North Korea.

These interviews with founders, blockchain researchers and industry experts suggest that North Korean IT workers are far more prevalent in the crypto industry than previously thought. Nearly every hiring manager interviewed for this article admitted that they had interviewed suspected North Korean developers, hired them without knowing it, or knew someone who had done so.

“Across the crypto industry, the percentage of resumes, job applicants or contributors coming from North Korea is probably over 50%,” said Zaki Manian, a prominent blockchain developer who said he inadvertently hired two North Korean IT workers in 2021 to help develop the Cosmos Hub blockchain. “Everyone is trying to screen these people out.”

The unwitting North Korean employers found by CoinDesk include several well-known blockchain projects, such as Cosmos Hub, Injective, ZeroLend, Fantom, Sushi and Yearn Finance. “This was all happening behind the scenes,” Manian said.

The investigation is the first time these companies have publicly acknowledged that they had inadvertently hired North Korean IT workers.

In many cases, North Korean workers work like regular employees; so, in a sense, employers essentially get what they pay for. But CoinDesk found evidence that these employees then wired their salaries to blockchain addresses associated with the North Korean government.

CoinDesk’s investigation also uncovered several cases where crypto projects that hired North Korean IT workers were later hacked. In some of these cases, it was possible to tie the theft directly to suspected North Korean IT employees on the company’s payroll. This was the case with Sushi, a well-known DeFi protocol that lost $3 million in a 2021 hack.

The U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) and the Department of Justice began publicizing North Korea’s attempts to infiltrate the U.S. cryptocurrency industry in 2022. Evidence uncovered by CoinDesk suggests that North Korean IT workers began working at cryptocurrency companies under false identities long before that, at least as early as 2018.

“I think a lot of people have made the mistake of thinking this is something that just happened all of a sudden,” Manian said. “These people had GitHub accounts and other things going back to 2016, 2017, 2018.” (GitHub, owned by Microsoft, is an online platform used by many software organizations to host code and allow developers to collaborate.)

CoinDesk used a variety of methods to connect North Korean IT workers to companies, including blockchain payment records, public GitHub code contributions, emails from U.S. government officials and direct interviews with the target companies. One of the largest North Korean payment networks CoinDesk investigated was discovered by blockchain investigator ZachXBT, who published a list of suspected North Korean developers in August.

Previously, employers had remained silent for fear of unwanted exposure or legal consequences. Now, faced with a trove of payment records and other evidence unearthed by CoinDesk, many of them have decided to come forward and share their stories for the first time, revealing the huge success and scale of North Korea’s infiltration of the cryptocurrency industry.

Fake documents

After hiring Ryuhei, the ostensibly Japanese employee, Rust’s Truflation was flooded with new applications. In just a few months, Rust had unwittingly hired four more North Korean developers who said they were based in Montreal, Vancouver, Houston and Singapore.

The crypto industry is particularly vulnerable to disruption by North Korean IT workers. The crypto industry has a very global workforce, and crypto companies are often more willing to hire fully remote (and even anonymous) developers than other companies.

CoinDesk reviewed North Korean job applications that crypto companies received from a variety of sources, including messaging platforms like Telegram and Discord, crypto-specific job boards like Crypto Jobs List and recruiting sites like Indeed.

“The place they’re most likely to be hired is from really fresh, newly minted teams that are willing to hire from Discord,” said Taylor Monahan, a product manager at crypto wallet app MetaMask who frequently publishes security research related to North Korean crypto activity. “They don’t have processes in place to hire people who have been background checked. They’re willing to pay in crypto a lot of times.”

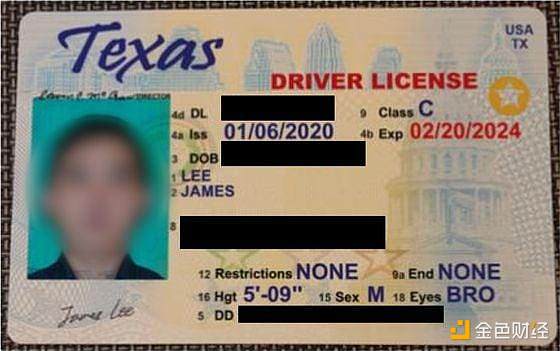

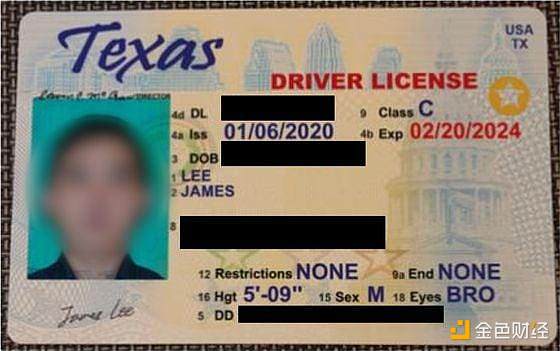

Rust said he runs background checks on all new hires at Truflation. “They sent us their passports and IDs, gave us the GitHub repository, ran tests, and then we basically hired them.”

An applicant who submitted a Texas driver’s license as identification to cryptocurrency firm Truflation is now suspected of being a North Korean citizen. CoinDesk is withholding some details because North Korean IT workers have a history of using stolen IDs. (Photo courtesy of Stefan Rust)

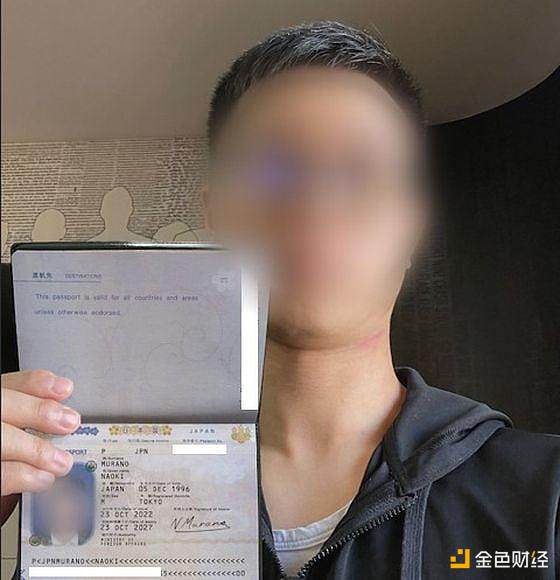

To the layperson, most forged documents are indistinguishable from real passports and visas, but experts told CoinDesk that professional background check services are likely to spot the forgeries.

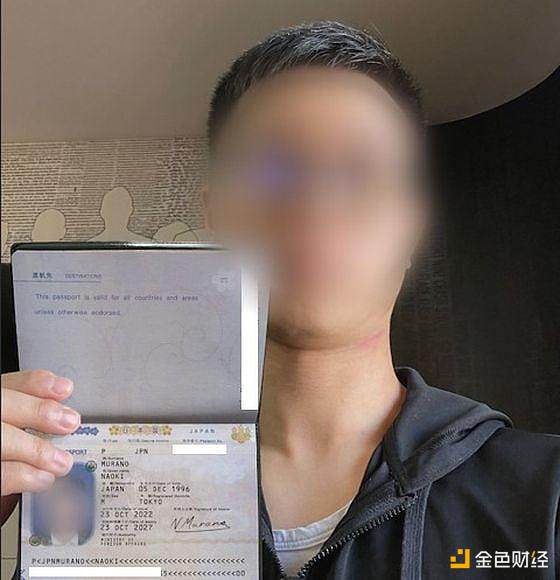

One of the suspected North Korean IT employees identified by ZachXBT, "Naoki Murano," provided the company with a seemingly authentic Japanese passport. (Photo courtesy of Taylor Monahan)

One of the suspected North Korean IT employees identified by ZachXBT, "Naoki Murano," provided the company with a seemingly authentic Japanese passport. (Photo courtesy of Taylor Monahan)

While startups are unlikely to use professional background investigators, "we do see North Korean IT people at large companies, either as real employees or at least contractors," Monahan said.

Hiding in plain sight

In many cases, CoinDesk found IT workers at North Korean companies using publicly available blockchain data.

In 2021, blockchain developer Manian's company, Iqlusion, needed some help. He looked for freelance programmers who might help with a project to upgrade the popular Cosmos Hub blockchain. He found two new hires; they performed well.

Manian had never met the freelancers, “Jun Kai” and “Sarawut Sanit,” in person. They had previously worked together on an open-source software project funded by the closely related blockchain network THORChain, and they told Manian they were in Singapore.

“I spoke to them almost every day for a year,” Manian said. “They got the job done. And frankly, I was very satisfied.”

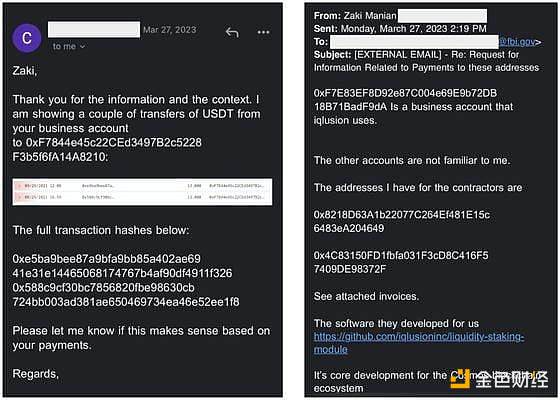

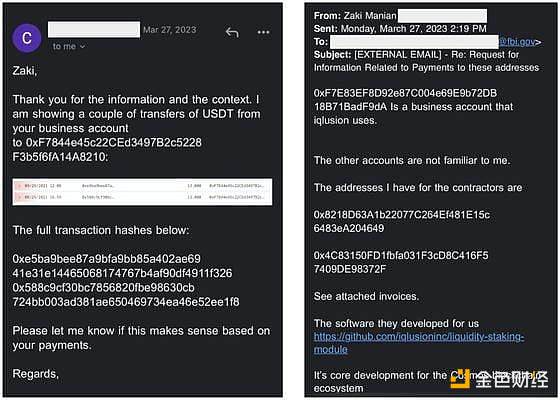

Two years after the freelancers completed their work, Manian received an email from an FBI agent who was investigating token transfers that appeared to come from Iqlusion and were being sent to suspected North Korean crypto wallet addresses. The transfers in question turned out to be payments from Iqlusion to Kai and Sanit.

Left: An FBI agent (name removed) asks Zaki Manian for information about two blockchain payments from his company, Iqlusion. Right: Manian told the agent the transactions were between Iqlusion and multiple contractors.

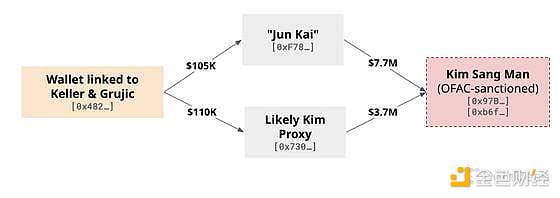

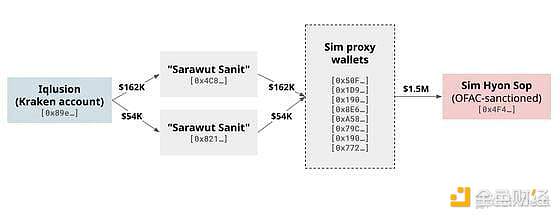

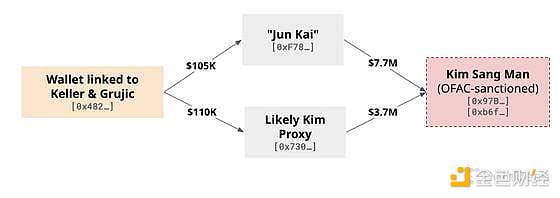

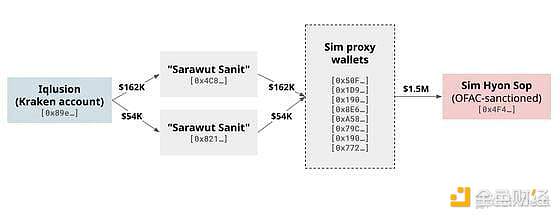

The FBI never confirmed to Manian that the developers he contracted were North Korean agents, but a CoinDesk review of Kai and Sanit’s blockchain addresses showed that during 2021 and 2022 they wired revenue to two individuals on the OFAC sanctions list: Kim Sang Man and Sim Hyon Sop.

Sim was a representative of North Korea’s Kwangson Bank, which laundered IT workers’ funds to help “finance North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction and ballistic missile programs,” according to OFAC. Sarawut appears to have wired all of his earnings to Sim and other blockchain wallets associated with Sim.

Blockchain records from April to December 2022 show that “Sarawut Sanit” sent all of his wages to a wallet associated with Sim Hyon Sop, an OFAC-approved North Korean agent. (A selection of Ethereum wallets tracked by CoinDesk. Asset prices estimated by Arkham.)

Kai, meanwhile, wired nearly $8 million directly to Kim. According to the 2023 OFAC advisory, Kim was a representative of the North Korean-run Chinyong Information Technology Cooperation, which “employed delegations of North Korean IT workers working in Russia and Laos through companies it controlled and its representatives.” Throughout 2021, “Jun Kai” sent $7.7 million worth of cryptocurrency directly to blockchain addresses on the OFAC sanctions list associated with Kim Sang Man. (A selection of Ethereum wallets tracked by CoinDesk. Asset prices estimated by Arkham.) Iqlusion’s salary to Kai accounted for less than $50,000 of the nearly $8 million he gave Kim, with the rest of the money coming in part from other cryptocurrency companies.

For example, CoinDesk found that the Fantom Foundation, which develops the widely used Fantom blockchain, made payments to “Jun Kai” and another developer with ties to North Korea.

“Fantom did confirm that two external individuals were involved with North Korea in 2021,” a Fantom Foundation spokesperson told CoinDesk. “However, the developers involved were involved in an external project that was never completed and never deployed.”

According to the Fantom Foundation, “the two employees involved have been fired, they never contributed any malicious code, never accessed Fantom’s codebase, and Fantom’s users were not impacted.” The spokesperson said a North Korean employee attempted to hack Fantom’s servers but failed because they lacked the necessary access.

According to the OpenSanctions database, Kim’s blockchain address associated with North Korea was not published by the government until May 2023, more than two years after the Iqlusion and Fantom payments were made.

Giving wiggle room

The U.S. and the United Nations imposed sanctions on hiring North Korean IT workers in 2016 and 2017, respectively.

It’s illegal to pay North Korean workers in the U.S., whether you know it or not — a legal concept known as “strict liability.”

It doesn’t matter where the company is located: Hiring North Korean workers poses a legal risk for any company doing business in a country with sanctions against North Korea.

Yet the U.S. and other U.N. member states have yet to prosecute crypto companies that employ North Korean IT workers.

The U.S. Treasury Department opened an investigation into U.S.-based Iqlusion, but Manian said the investigation ended without any penalties.

U.S. authorities have been lenient about bringing charges against the companies — a sort of acknowledgment that they were the victims of an unusually sophisticated and sophisticated identity fraud at best, or a most humiliating and long-running scam at worst.

Besides the legal risks, MetaMask’s Monahan explained that paying North Korean IT workers is also “bad because you’re paying people who are essentially being exploited by the regime.”

According to the 615-page report by the United Nations Security Council, North Korean IT workers are only allowed to keep a small portion of their wages. “Low earners keep 10%, while high earners can keep 30%,” the report states.

While those salaries may still be high relative to the North Korean average, “I don’t care where they live,” Monahan said. “If I’m paying someone and they’re forced to send their entire salary to their boss, that would make me very uncomfortable. And if their boss is the North Korean regime, that would make me even more uncomfortable.”

CoinDesk reached out to multiple suspected North Korean IT workers during the course of this story but has yet to hear back.

The Future

CoinDesk identified more than 20 companies that may employ North Korean IT workers by analyzing blockchain payment records for OFAC-sanctioned entities. Twelve companies that submitted records confirmed to CoinDesk that they had previously found suspected North Korean IT employees on their payrolls.

Some declined to comment further for fear of legal consequences, but others agreed to share their stories in the hope that others can learn from their experiences.

In many cases, North Korean employees are easier to identify once they’re hired.

Eric Chen, CEO of Injective, a project focused on decentralized finance, said he signed on a freelance developer in 2020 but quickly fired him for poor performance.

“He didn’t last long,” Chen said. “He wrote terrible code and it didn’t work well.” Chen didn’t know the employee had ties to North Korea until last year, when a U.S. “government agency” contacted Injective.

Several companies told CoinDesk they fired an employee before they learned of any ties to North Korea — citing substandard work quality.

‘A few months of payroll’

North Korean IT workers, however, are similar to typical developers, with varying degrees of competence.

On one hand, you have employees who “come to the company, go through the interview process, and make a few months of payroll,” Manian said. “And then there’s the other side of that, when you interview these people, you find out that their actual technical ability is really strong.”

Rust recalled meeting “a really good developer” while at Truflation who claimed to be from Vancouver, but turned out to be from North Korea. “He was a really young guy,” Rust said. “It felt like he was fresh out of college. Kind of green, very enthusiastic, very excited to have the opportunity to work.”

In another example, DeFi startup Cluster fired two developers in August after ZachXBT provided evidence that the two developers had ties to North Korea.

“It was really unbelievable how much these people knew,” Cluster’s pseudonymous founder z3n told CoinDesk. In retrospect, there were some “obvious red flags.” For example, “they change their payment addresses every two weeks, their Discord names or Telegram names every month or so.”

Webcams turned off

In conversations with CoinDesk, many employers said they noticed anomalies when they learned their employees might be North Korean, which made more sense.

Sometimes the hints were subtle, like an employee’s work hours not matching their supposed work location.

Other employers, like Truflation, noticed that multiple people might be posing as one, and that employees would hide this by turning off their webcams. (They were almost all men.

One company hired an employee who would attend meetings in the morning but seemed to forget everything that was discussed later in the day, even though she had spoken to multiple people before.

When Rust expressed his concerns about “Japanese” employee Ryuhei to an investor with experience tracking criminal payment networks, the investor quickly identified four other suspected North Korean IT workers on Truflation’s payroll.

“We cut ties immediately,” Rust said, adding that his team conducted a security audit of its code, enhanced its background check process and changed certain policies. One of the new policies required remote workers to turn on their cameras.

$3M Hack

Many employers consulted by CoinDesk mistakenly believed that North Korean IT workers operated independently of North Korea’s hacking division, but blockchain data and conversations with experts suggest that North Korean hacking and IT workers are often linked.

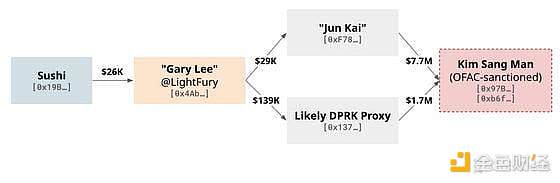

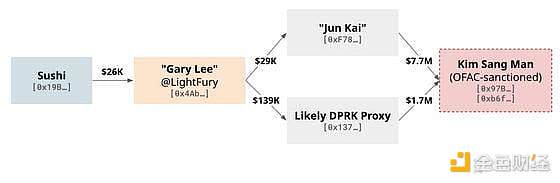

In September 2021, MISO, a platform built by Sushi to issue crypto tokens, lost $3 million in a theft. CoinDesk found evidence that the attack was linked to Sushi’s hiring of two developers whose blockchain payment records were linked to North Korea.

At the time of the hack, Sushi was one of the most watched platforms in the emerging DeFi space. More than $5 billion has been deposited into SushiSwap, a platform that essentially functions as a “decentralized exchange” for people to trade cryptocurrencies without an intermediary.

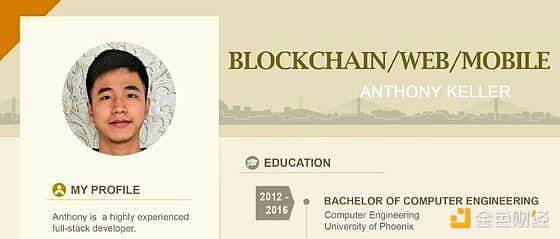

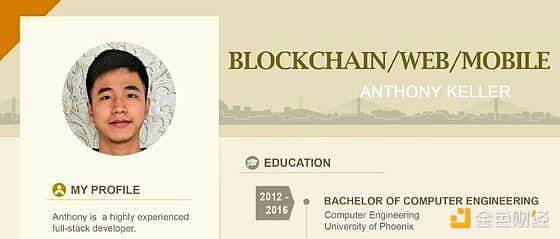

Sushi’s chief technology officer at the time, Joseph Delong, traced the MISO theft to two freelance developers who worked on the platform: They used the names Anthony Keller and Sava Grujic. Delong said those developers (who he now suspects are the same person or group) injected malicious code into the MISO platform that transferred funds to wallets they controlled.

When Keller and Grujic were hired by Sushi DAO, the decentralized autonomous organization that manages the Sushi protocol, they provided credentials that were typical enough for an entry-level developer, even impressive.

Keller used the pseudonym “eratos1122” in public, but when he applied for a job at MISO, he used what appeared to be his real name, “Anthony Keller.” In a resume Delong shared with CoinDesk, Keller claims to live in Gainesville, Georgia, and graduated from the University of Phoenix with a bachelor’s degree in computer engineering. (The university did not respond to a request for information about whether it has a graduate with the same name.)

“Anthony Keller” claims to live in Gainesville, Georgia, and his resume lists his work experience at the popular decentralized finance app Yearn.

Keller’s resume does mention previous jobs. The most impressive of these was Yearn Finance, a very popular crypto investment protocol that offers users a way to earn interest through a range of investment strategies. Banteg, a core developer at Yearn, confirmed that Keller worked on Coordinape, an app developed by Yearn to help teams collaborate and facilitate payments. (Banteg, says Keller’s work was limited to Coordinape, and he had no access to Yearn’s core codebase.)

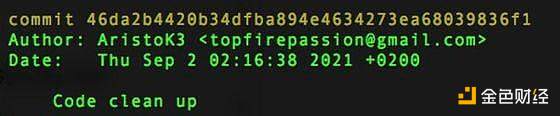

Keller introduced Grujic to MISO, and the two described themselves as “friends,” according to Delong. Like Keller, Grujic provided a resume that listed his real name, not his online pseudonym “AristoK3.” He claims to be from Serbia and graduated from the University of Belgrade with a bachelor’s degree in computer science. His GitHub account is active, and his resume lists his work experience at several smaller crypto projects and gaming startups.

In his resume, “Sava Grujic” lists five years of programming experience and claims to be based in Belgrade, Serbia.

Rachel Chu, a former core developer at Sushi who worked closely with Keller and Grujic before the theft, said she had become “suspicious” about the two before the hack.

Despite the distance between them, Grujic and Keller had “the same accent” and “the same way of texting,” Chu said. “Every time we spoke, they had some background noise, like they were in a factory,” she added. Chu recalled seeing Keller’s face but never Grujic’s. Keller’s camera was “zoomed in,” according to Chu, so she couldn’t see what was behind him.

Grujic and Keller eventually stopped contributing to MISO around the same time. “We thought they were the same person,” Delong said, “so we stopped paying them.” It was not uncommon for remote cryptocurrency developers to impersonate multiple people to earn extra income from payroll during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

After Grujic and Keller were fired in the summer of 2021, the Sushi team neglected to revoke their access to the MISO codebase.

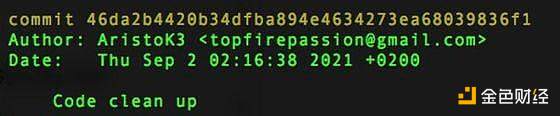

Grujic, under his “Aristok3” screen name, submitted malicious code to the MISO platform on Sept. 2, transferring $3 million to a new cryptocurrency wallet, according to a screenshot obtained by CoinDesk.

“Sava Grujic” submitted tainted code to Sushi’s MISO using the pseudonym AristoK3. (Screenshot courtesy of Joseph Delong)

“Sava Grujic” submitted tainted code to Sushi’s MISO using the pseudonym AristoK3. (Screenshot courtesy of Joseph Delong)

A CoinDesk analysis of blockchain payment records suggests a possible connection between Grujic, Keller and North Korea. In March 2021, Keller posted a blockchain address in a now-deleted tweet. CoinDesk found multiple payments between that address, Grujic’s hacker address, and Keller’s address on file with Sushi. According to Delong, Sushi’s internal investigation ultimately concluded that the address belonged to Keller.

Between 2021 and 2022, blockchain addresses tied to Keller and Grujic sent most of the funds to wallets associated with North Korea. (A selection of Ethereum wallets tracked by CoinDesk. Asset prices are estimated by Arkham.)

CoinDesk found that the address sent most of the funds to “Jun Kai” (the Iqlusion developer who sent money to OFAC-sanctioned Kim Sang Man) and another wallet that appeared to act as a North Korean proxy (because it also paid Kim).

Sushi’s internal investigation found that Keller and Grujic frequently operated from Russian IP addresses, further supporting the claim that they were North Korean. OFAC says North Korean IT workers are sometimes based in Russia. (The U.S. phone number on Keller’s resume is no longer in service, and his “eratos1122” Github and Twitter accounts have been deleted.)

In addition, CoinDesk found evidence that Sushi hired another suspected North Korean IT contractor at the same time as Keller and Grujic. ZachXBT calls the developer "Gary Lee," who coded under the pseudonym LightFury and wired earnings to "Jun Kai" and another proxy address associated with Kim.

From 2021 to 2022, Sushi also employed another apparent North Korean contractor named "Gary Lee." The worker wired his 2021-2022 earnings to blockchain addresses associated with North Korea, including a wallet used by Iqlusion's "Jun Kai." (A selection of Ethereum wallets tracked by CoinDesk. Asset prices are estimated by Arkham.)

Grujic returned the stolen funds after Sushi publicly blamed the attack on Keller’s pseudonym “eratos1122” and threatened to involve the FBI. While it seems counterintuitive that North Korean IT workers would care about protecting fake identities, North Korean IT workers appear to reuse certain names and build their reputations by contributing to many projects, perhaps to gain the trust of future employers.

One might argue that protecting the Anthony Keller alias is more profitable in the long run: In 2023, two years after the Sushi incident, an individual named “Anthony Keller” applied to Stefan Rust’s company Truflation.

CoinDesk attempted to contact “Anthony Keller” and “Sava Grujic” for comment but was unsuccessful.

North Korean heist

North Korea has stolen more than $3 billion in cryptocurrency through hacking over the past seven years, according to the United Nations. Blockchain analysis firm Chainalysis tracked 15 hacking attacks linked to North Korea in the first half of 2023, "about half of which involved thefts involving IT workers," said Madeleine Kennedy, a spokeswoman for the company.

North Korea's cyberattacks are not like the Hollywood version of hacking, with hoodie-wearing programmers using complex computer code and black-and-green computer terminals to break into mainframes.

North Korean attacks are decidedly low-tech. They typically involve some form of social engineering, where attackers gain the trust of victims who hold system keys and then extract those keys directly through simple means such as malicious email links.

“We’ve never seen a real attack from North Korea so far,” Monahan said. “It’s always social engineering first, then compromising the device, then stealing the private keys.”

IT workers are well-suited to contribute to North Korea’s heists, either by obtaining personal information that can be used to compromise potential targets or by directly accessing software systems that are rife with digital cash.

A series of coincidences

On Sept. 25, as this article was about to go to press, CoinDesk scheduled a video call with Truflation’s Rust. The plan was to verify some of the details he had previously shared.

A flustered Rust joined the call 15 minutes late. He had just been hacked.

CoinDesk contacted more than 20 projects that appeared to have been duped into hiring North Korean IT workers. Two of them had been hacked in the last two weeks of the interview alone: Truflation and a cryptocurrency lending app called Delta Prime.

It’s too early to tell whether the two hacks are directly linked to the unintentional hiring of North Korean IT employees.

Delta Prime was first hacked on Sept. 16. CoinDesk previously uncovered payments and code contributions between Delta Prime and Naoki Murano, one of the developers touted by anonymous blockchain sleuth ZachXBT as having ties to North Korea.

The project lost more than $7 million, with officials saying it was due to “compromised private keys.” Delta Prime did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The Truflation hack came less than two weeks later. About two hours before speaking with CoinDesk, Rust noticed a flow of funds out of his crypto wallet. He had just returned from a business trip to Singapore and was trying to figure out what he had done wrong. “I just don’t know how it happened,” he said. "I locked my laptops in a safe on the wall of the hotel. I always had my phone with me."

As Rust spoke, millions of dollars were flowing out of his personal blockchain wallet. "I mean, it's really bad. This is money for my children's tuition and pension."

Truflation and Rust ultimately lost about $5 million. Officials determined that the cause of the loss was the theft of private keys.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

One of the suspected North Korean IT employees identified by ZachXBT, "Naoki Murano," provided the company with a seemingly authentic Japanese passport. (Photo courtesy of Taylor Monahan)

One of the suspected North Korean IT employees identified by ZachXBT, "Naoki Murano," provided the company with a seemingly authentic Japanese passport. (Photo courtesy of Taylor Monahan)

“Sava Grujic” submitted tainted code to Sushi’s MISO using the pseudonym AristoK3. (Screenshot courtesy of Joseph Delong)

“Sava Grujic” submitted tainted code to Sushi’s MISO using the pseudonym AristoK3. (Screenshot courtesy of Joseph Delong)