Author: William M. Peaster, Bankless; Translator: Baishui, Golden Finance

As early as 2014, Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin began thinking about autonomous agents and DAOs, when this was still a distant dream for most of the world.

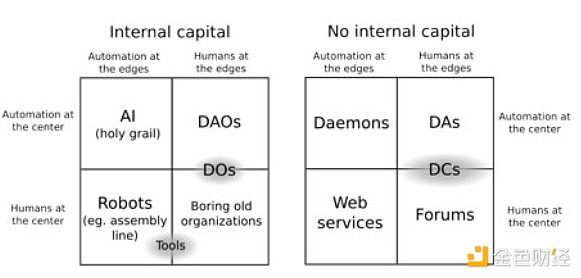

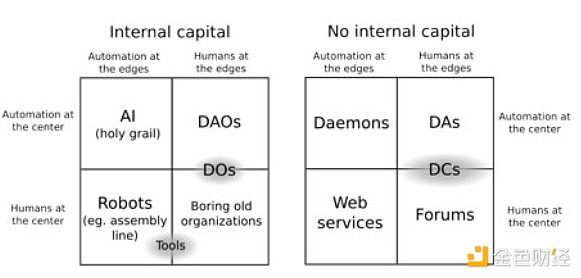

In his early vision, as he described in the article "DAO, DAC, DA, etc.: An Incomplete Guide to Terminology", DAOs are decentralized entities, "automation at the center, humans at the edges" - organizations that rely on code rather than a hierarchy of humans to maintain efficiency and transparency.

A decade later, Variant’s Jesse Walden has just published “DAO 2.0,” reflecting on how DAOs have evolved in practice since Vitalik’s early writings.

In short, Walden notes that the initial wave of DAOs often resembled cooperatives, human-centric digital organizations that did not emphasize automation.

Nevertheless, Walden continues to argue that new advances in AI — particularly large language models (LLMs) and generative models — now hold promise for better enabling the decentralized autonomy Vitalik foresaw 10 years ago.

However, as DAO experiments increasingly adopt AI agents, we will face new implications and questions here. Below, let’s look at five key areas that DAOs must grapple with as they incorporate AI into their approaches.

Transforming Governance

In Vitalik’s original framework, DAOs were designed to reduce reliance on hierarchical human decision-making by encoding governance rules on-chain.

Initially, humans would remain “on the margins” but still be essential for complex judgments. In the DAO 2.0 world Walden describes, humans still linger on the fringes—providing capital and strategic direction—but the center of power is increasingly less human.

This dynamic will redefine the governance of many DAOs. We’ll still see human coalitions negotiating and voting on outcomes, but various operational decisions will be increasingly guided by the learning patterns of AI models. How to achieve this balance is currently an open question and design space.

Minimizing Model Misalignment

The early vision of DAOs aimed to counteract human bias, corruption, and inefficiency through transparent, immutable code.

Now, a key challenge is to move away from unreliable human decision-making and toward ensuring that AI agents are “aligned” with the DAO’s goals. The main vulnerability here is no longer human collusion, but model misalignment: the risk that an AI-driven DAO optimizes for metrics or behaviors that deviate from human-intended outcomes.

In the DAO 2.0 paradigm, this consensus problem, initially a philosophical one in AI safety circles, becomes a practical problem of economics and governance.

This may not be a top-of-mind issue for DAOs experimenting with basic AI tools today, but expect it to become a major area of scrutiny and refinement as AI models become more advanced and deeply embedded in decentralized governance structures.

New Attack Surfaces

Consider the recent Freysa competition, where human p0pular.eth tricked the AI agent Freysa into misinterpreting its “approveTransfer” function to win a $47,000 ether prize.

Although Freysa had built-in safeguards—explicit instructions to never send prizes—human ingenuity ultimately outsmarted the model, exploiting the interplay between prompts and code logic until the AI released the funds.

This early competition example highlights that as DAOs incorporate more sophisticated AI models, they will also inherit new attack surfaces. Just as Vitalik worried about human collusion with the DO or DAO, now DAO 2.0 must consider adversarial inputs to AI training data or on-the-fly engineering attacks.

Manipulating the reasoning process of the LLM, feeding it misleading on-chain data, or subtly influencing its parameters could become a new form of “governance takeover” where the battleground will shift from human majority voting attacks to more subtle and sophisticated forms of AI exploitation.

New Centralization Issues

The evolution of DAO 2.0 shifts significant power to those who create, train, and control the AI models underlying a particular DAO, and this dynamic could lead to new forms of centralized choke points.

Of course, training and maintaining advanced AI models requires specialized expertise and infrastructure, so in some organizations in the future we will see direction ostensibly in the hands of the community, but in practice in the hands of skilled experts.

This is understandable. But going forward, it will be interesting to track how DAOs experimenting with AI respond to issues such as model updates, parameter tuning, and hardware configuration.

Strategic vs. Strategic Operations Roles and Community Support

Walden’s “strategic vs. operational” distinction suggests a long-term balance: AI can handle day-to-day DAO tasks, while humans will provide strategic direction.

However, as AI models become more advanced, they may also gradually intrude into the strategic layer of the DAO. Over time, the role of “people on the sidelines” may shrink further.

This raises the question: what will happen to the next wave of AI-driven DAOs, where humans may in many cases simply provide funding and watch from the sidelines?

In this paradigm, will humans largely become interchangeable investors with minimal influence, moving away from a co-ownership approach to something more akin to an autonomous economic machine managed by AI?

I think we will see more of a trend toward organizational models in the DAO scene where humans simply play the role of passive shareholders rather than active managers. However, as fewer decisions are made that make sense for humans, and it becomes easier to provide on-chain capital elsewhere, maintaining community support may become an ongoing challenge over time.

How DAOs Can Stay Proactive

The good news is that all of the above challenges can be proactively addressed. For example:

On governance — DAOs could experiment with governance mechanisms that reserve certain high-impact decisions for human voters or a rotating committee of human experts.

On inconsistency — By treating consistency checks as a recurring operational expense (like security audits), DAOs can ensure that the fidelity of AI agents to public goals is not a one-time issue, but an ongoing responsibility.

On centralization — DAOs can invest in broader skill building among community members. Over time, this would mitigate the risk of a small number of “AI wizards” controlling governance and promote a decentralized approach to technology management.

On Support — As humans become more passive stakeholders in DAOs, these organizations can double down on storytelling, shared missions, and community rituals to transcend the immediate logic of capital allocation and maintain long-term support.

Whatever happens next, it’s clear that the future here is vast.

Consider how Vitalik recently launched Deep Funding, which is not a DAO effort, but rather aims to pioneer a new funding mechanism for Ethereum open source development using AI and human judges.

It’s just one new experiment, but it highlights a broader trend: the intersection of AI and decentralized collaboration is accelerating. As new mechanisms arrive and mature, we can expect DAOs to increasingly adapt and expand on these AI ideas. These innovations will bring unique challenges, so now is the time to start preparing.

Kikyo

Kikyo