Source: Chainalysis; Compiled by: Baishui, Golden Finance

In 2024, the cryptocurrency ecosystem has seen many positive developments. Cryptocurrencies continue to gain mainstream acceptance in many ways following the approval of spot Bitcoin and Ethereum exchange-traded products (ETPs) in the United States and the revision of the U.S. Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) fair accounting rules. In addition, the inflows into legal services year-to-date are the highest since 2021, the peak of the last bull market. In fact, the total illegal activity year-to-date has dropped by 19.6%, from $20.9B to $16.7B, indicating that legal activity is growing faster than on-chain illegal activity. This is an encouraging sign for the continued adoption of cryptocurrencies around the world.

These global trends are also reflected in the Japanese crypto ecosystem. Overall, Japanese services are generally less exposed to global illegal entities, such as sanctioned entities, darknet markets (DNMs), and ransomware services, as most Japanese services are primarily targeted at Japanese users. However, this does not mean that Japan is completely immune to cryptocurrency-related crimes. Public reports, including from Japan’s Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) Japan Financial Intelligence Center (JAFIC), have highlighted that cryptocurrencies pose a significant money laundering risk. While Japan’s exposure to international illicit entities may be limited, the country is not without its own local challenges. Off-chain criminal entities that exploit cryptocurrencies are prevalent.

In this article, we’ll explore two key cryptocurrency crime issues that deserve close attention in Japan: money laundering and scams.

Money Laundering and Cryptocurrency

First, let’s explore the relationship between money laundering and cryptocurrency. Money laundering in the context of cryptocurrency is often associated with concealing the proceeds of on-chain crimes, such as DNMs and ransomware. But as the world continues to embrace cryptocurrency, illicit actors are also eager to take advantage of powerful new technologies. With the right tools and knowledge, investigators can leverage the transparency of blockchain to uncover and disrupt illicit activity both on-chain and off-chain.

Crypto-native Money Laundering

The process of laundering funds obtained on-chain is often complex, as cybercriminals use a variety of services to obscure the source and movement of funds. Crypto-native money laundering presents an ongoing challenge for cryptocurrency services and law enforcement agencies.

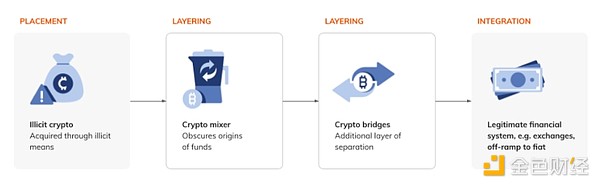

The first stage of crypto-native money laundering – placement – always involves cryptocurrency. Despite the transparency of blockchain, criminals often choose cryptocurrency for money laundering because it is often easier to create private wallets that do not require know-your-customer (KYC) information than to launder money through traditional placement strategies such as money mules. The intermediate stages of money laundering (layering) can take many forms. In traditional fiat money laundering, this may involve sending funds through multiple bank accounts and/or shell companies. In cryptocurrency, this can involve:

Intermediary Wallets or Hopping:The use of multiple individual wallets complicates tracing and often accounts for more than 80% of the total value flowing through these money laundering corridors. For investigators and compliance professionals using Chainalysis, detecting illicit activity and tracing it through intermediary wallets can be relatively straightforward.

Crypto Obfuscation Services:Obfuscation services can take a number of different forms, such as mixers, cross-chain bridges, and privacy coins. While these services are widely used by money launderers, they also have legitimate privacy use cases and are not inherently illegal.

Cross-chain bridges: These services and protocols facilitate the transfer of assets between different blockchain networks, creating complex webs of transactions.

Privacy coins: Tokens like Monero and Zcash use advanced cryptography to hide transaction details, which makes them attractive to illicit actors.

Stablecoins: Increasingly, they have become the preferred vehicle for illicit money transfers, reflecting the overall growth in stablecoin adoption around the world over the past few years. But using stablecoins also increases the risk for money launderers, as many stablecoin issuers are responsive to authorities and have the ability to freeze funds.

Over-the-counter (OTC) brokers: OTC brokers are located around the world and can facilitate large trades with minimal scrutiny, often bypassing public order books and KYC requirements.

While some cybercriminals may keep their ill-gotten gains in personal wallets for years (presumably hoping that authorities will turn their attention elsewhere), most bad actors look to move funds from crypto to cash. More than 50% of illicit funds flow directly or indirectly to centralized exchanges after using obfuscation techniques. Illegal actors may turn to centralized exchanges for money laundering because of their high liquidity, easy crypto-to-fiat conversions, and integration with traditional financial services, which helps blend illicit funds with legitimate activities. Hundreds of centralized services currently receive more than $1 million in illicit funds each year.

Non-crypto-native money laundering

Traditional money launderers are using methods similar to fiat-based strategies to enter crypto. Unlike crypto-native money laundering, non-crypto-native money laundering begins with a placement phase involving fiat currency. Typically, criminals will first use a bank account to deposit fiat funds and then convert them into cryptocurrency. Criminals can then layer their funds in, just like crypto-native money laundering.

Non-cryptocurrency-native money laundering involves off-chain criminal activity, such as drug trafficking and fraud. Identifying novel on-chain money laundering patterns often reflects the detection of unusual fiat-based transactions and patterns. In non-cryptocurrency-native money laundering, on-chain analysis often starts with centralized exchanges, making it difficult to identify illegal transactions without additional context. While tracing the movement of these funds can be challenging due to a lack of evidence, data science techniques can flag indicators of potential non-cryptocurrency-native money laundering.

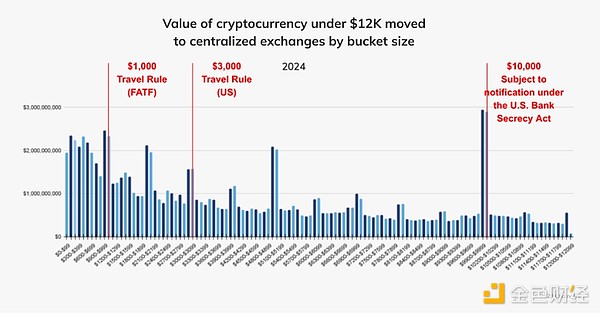

One way to identify non-cryptocurrency-native money laundering is by repeating transfers below reporting thresholds, which we discuss in more detail in our 2024 Cryptocurrency Money Laundering Report. While these thresholds vary by country, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF)—the international body that sets AML/CFT standards—recommends that cryptocurrency transactions over $1,000 USD/EUR be subject to the travel rule. Authorities set this threshold at $3,000 USD. Additionally, the U.S. Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) requires reporting of cash transactions over $10,000 USD.

Transactions above these values trigger additional scrutiny, while transactions below these thresholds, even for as little as a dollar, do not face the same level of scrutiny.

The chart below shows the value of funds transferred to centralized exchanges by transfer size from the year to date in 2024. It shows a significant surge in transfer amounts just below and just above the reporting thresholds of $1,000, $3,000, and $10,000. Transfers just above these thresholds can likely be attributed to rounding differences in exchange rates. Such surges are typical of bad actors who adjust payment methods to avoid triggering reporting requirements. Transactions just below reporting requirements are one of the red flag indicators that the FATF highlights in its guidance for Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASPs) to help identify suspicious behavior.

Consolidating Funds

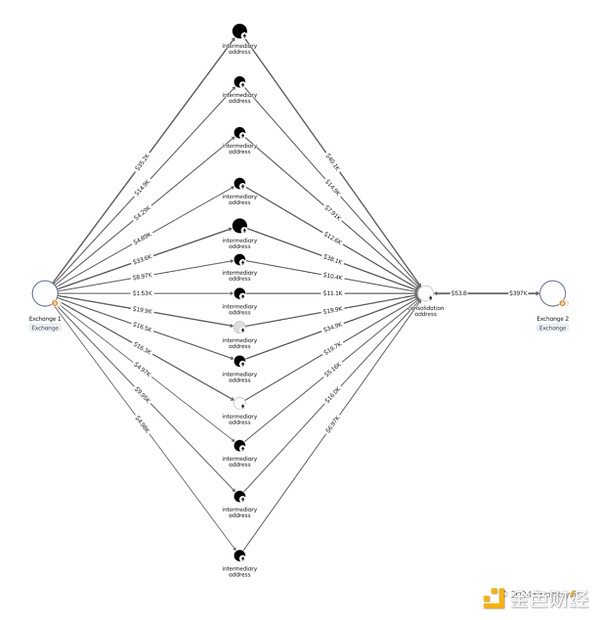

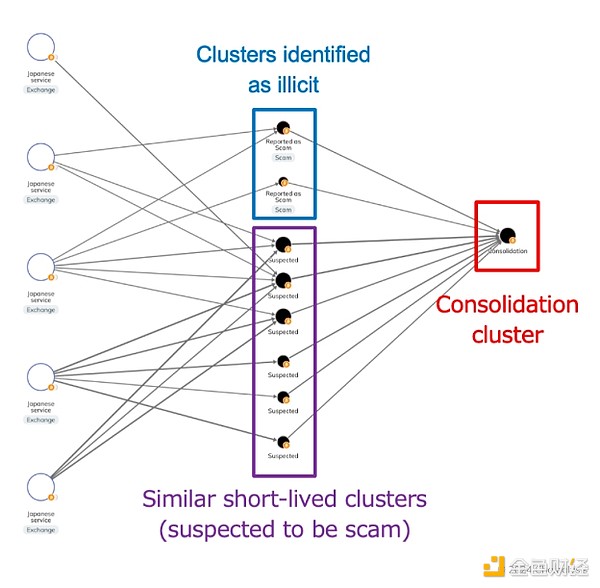

Exchanges may also benefit from monitoring consolidated wallets that interact with their services. When money launderers layer funds through many intermediary wallets, the transaction flow is often not simple and linear. Instead, money launderers may split funds into many different wallets and then re-consolidate the funds after multiple transactions.

Consolidated wallets receive and consolidate funds from multiple wallets or sources. If funds are transferred through multiple independent intermediary wallets and then consolidated at a single address, this may indicate an attempt to avoid detection.

The Chainalysis cryptocurrency investigation diagram below shows such behavior in a known scam ring that targets the elderly. In this case, the scammers may instruct victims to purchase crypto assets using a specific service, Exchange 1. Each victim was then instructed to send funds to a different wallet controlled by the scammers. The scammers then consolidated these funds into a single wallet and cashed out at Exchange 2.

Exchange 1’s compliance team would have a difficult time directly connecting the victims to the scammers, especially if the intermediary addresses were one-offs with no prior illicit relationship, unless they traced the transactions back to the consolidating wallet. Using many intermediaries prior to consolidation is a well-known tactic that prevents Exchange 1’s compliance team from understanding the connections between all the victims who sent funds.

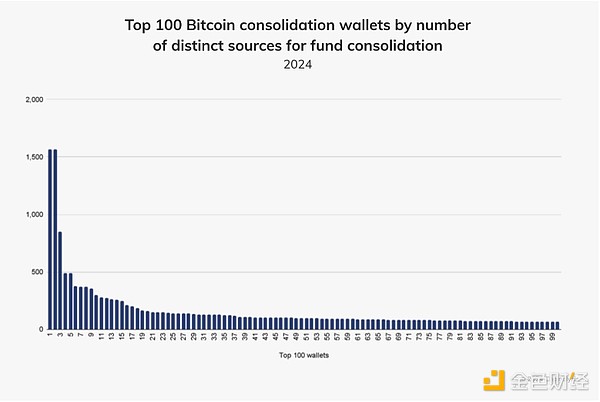

While the example above is relatively simple, more complex money laundering networks feature consolidating wallets that aggregate funds from dozens or even hundreds of intermediary wallets. Querying Chainalysis data allows investigators to find major consolidation wallets, which can often serve as useful clues. For example, the top 100 Bitcoin consolidation wallets in 2024 year-to-date — all of which are two-hop transactions from exchanges — received nearly $1 billion ($968 million) worth of Bitcoin from more than 14,970 different addresses.

Broadening the scope further, we found that more than 1,500 consolidation wallets received a total of $2.6B worth of Bitcoin in 2024; each of which received funds from at least ten different wallets. Again, we can't say for sure that this represents money laundering — in fact, most of it likely represents legitimate inflows. But this activity may warrant additional scrutiny.

Illegal Activity in Japan: Money Laundering and Scams

In Japan, based on our conversations with key industry players and statistics and documents released by local authorities, we have consistently observed that the most common illicit use of cryptocurrencies is money laundering from non-crypto native crimes and scams. We will discuss how these issues are perceived in Japan and explore how to estimate the extent of the damage caused by such crimes.

Money Laundering from Non-crypto Crime

As mentioned earlier, non-crypto native crime cases are difficult to track at scale without context - often only known to law enforcement, financial institutions, crypto services, and/or victims. Nonetheless, several of our clients have provided us with information that addresses the attribution issue, allowing us to better understand the state of non-crypto money laundering in Japan. Based on the information we have received to date, many of the illicit accounts on centralized exchanges are set up to receive fiat funds from traditional forms of fraud and phishing campaigns, stealing funds from online bank accounts. We published a blog last year discussing an on-chain analysis of a Japanese money laundering case that began with a non-crypto native crime.

According to 2023 statistics released by the Japan National Police Agency (JNPA), in 2023, a total of 19,038 fraud cases were reported in Japan, with total losses amounting to 45.26B yen (about $300 million). These figures exceed those for 2022, indicating that this type of fraud is still growing and remains a serious problem. Although these statistics do not address the amount of fiat currency converted into cryptocurrencies, as we explore later, we assess that a large portion of this is cryptocurrency-based money laundering.

According to a report published by the JNPA Cyber Affairs Bureau, in this case, nearly half of the funds reported stolen from online bank accounts, totaling 8.73B yen ($57.89 million), were sent to the bank accounts of cryptocurrency exchanges. These flows of funds indicate that cryptocurrencies are now used as a common tool for fraudsters to launder money.

Fraud Trends Affecting Japan

As mentioned in our Crypto Crime Report, fraud is one of the most serious illegal categories in cryptocurrency. We have previously identified clusters of notable cryptocurrency scams with touchpoints in Japan, but today, Japanese law enforcement agencies are also keeping a close eye on a new trend in scams – social media-based investment scams and romance scams.

Recent investment scams often place investment solicitation ads on major social media platforms to attract the attention of potential victims. Scammers impersonate well-known economists or celebrities to attract more followers, and direct them to group channels on popular messaging apps through URLs on the ads, where many of the fake members actively comment and applaud the channel host. Victims are drawn into conversations with the scammers (who often claim to be the channel owner or assistant) and are ultimately directed to trade on fake investment websites.

Romance scams, also known as “pig-killing scams” because bad actors say they “fatten” victims for the maximum possible value, are a significant and growing problem with cryptocurrency. Pig-killing scammers first establish a relationship with their victims (usually romantic, as the name suggests) for a period of time, usually initiating contact through pretend text messages sent to the wrong number or through dating apps. As the relationship deepens, the scammer will eventually push the victim to invest funds (sometimes in cryptocurrency, sometimes in fiat) into a fake investment opportunity and continue to do so until eventually severing contact.

The latest JNPA statistics on such scams show the following figures from January to August this year, which are significantly higher than last year:

Investment scams: 6,868 cases reported, totaling ¥64.14 billion ($424.97 million) – 9.9% of which were crypto

Romance scams: 4,639 cases reported, totaling ¥23.65 billion ($156.7 million) – 17.7% of which were crypto

After the Japanese government recognized this as a significant threat to Japanese citizens, the Cabinet held a meeting to discuss countermeasures and policies, including strengthening investigative capabilities for cryptocurrencies, preventing illegal bank withdrawals, and establishing a legal framework to fully support asset seizure and recovery.

Our On-Chain Analysis of Fraud and Scam Cases in Japan

While tracking off-chain money laundering activity at scale is difficult, we can follow the flow of funds when our clients alert us to the activity and provide the addresses and transactions involved, as we did last year. As we continue to work closely with our clients and partners in Japan to strengthen our data, particularly on off-chain money laundering activity, we can also analyze the state of fraud and scams in Japan involving cryptocurrencies.

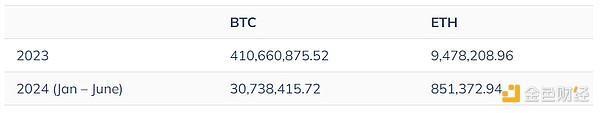

Below is the total received value for clusters reported as fraudulent accounts and scams in 2023 and 2024 (as of June).

Reported as a Scam (Non-Crypto Native) (Total Value Received from Japanese Exchanges) – USD

Reported as a Scam (Total Value Received from Japanese Exchanges) – USD

As always, we must caution that these numbers are lower-end estimates, especially for off-chain crime, as many scams and frauds go unreported.

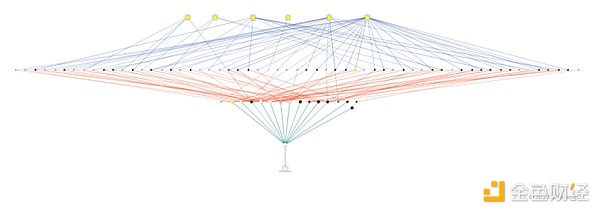

Nevertheless, these campaigns all share a common pattern: the use of consolidated wallets. While the initial addresses that receive funds directly from exchanges are distributed and ephemeral, funds from these addresses are ultimately sent to a much smaller number of private wallets and/or deposit addresses on exchanges.

When we narrowed down the cases involving ETH, we found that integrated wallets often used decentralized exchanges (DEX) or bridges to convert ETH to USDT.

How to read this graph:

– Blue: Funds flowed from Japanese exchanges to suspected scam addresses

– Red: Funds from the initial address to the first consolidation point

– Green: Funds from the first consolidation point to the second consolidation point

– Purple: Funds from the second consolidation point to the DEX (ETH<->USDT)

Given how quickly money launderers use new wallet addresses, it is not easy to track them individually in real time, but we can still identify common consolidation points from the clusters we have identified to estimate the scale of these illicit activities. In this case, we estimated the amount of potential illegal funds related to the Japanese case by following the following process:

Trace the funds that have been classified as Japanese illegal clusters to find the consolidation points;

At the consolidation points, aggregate the received exposure amounts from the Japanese flagged cluster and the Japanese exchange cluster.

Here’s what we found:

Estimated value of non-crypto native money laundering activity – USD

Estimated value of Japanese scams – USD

As mentioned previously, these estimates are consistent with those published by Japanese authorities.

The changes in money laundering tactics we are seeing from a wide range of threat actors serve as a reminder that the most sophisticated illicit actors are continually adapting their money laundering strategies and leveraging new types of crypto services. By studying these new on-chain money laundering methods and patterns, and learning how to disrupt them, law enforcement and compliance teams can be more effective.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance Clement

Clement Beincrypto

Beincrypto cryptopotato

cryptopotato Bitcoinist

Bitcoinist Bitcoinist

Bitcoinist Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph