Spain Ventures into the Digital Euro Landscape

Spain strategically positions itself within the realm of the digital euro, signaling a transformative trajectory for the financial landscape.

Hui Xin

Hui Xin

Author: Katrin Assenmacher, Massimo Ferrari Minesso, Arnaud Mehl and Maria Sole Pagliari; Source: ECB; Compiler: Cheng Xuyang, Renmin University of Finance and Technology Research Institute

In February 2024, the European Central Bank (ECB) published the article "Managing the transition to central bank digital currency". The author of this article established a two-country DSGE model considering financial frictions and studied the situation of a central bank digital currency (CBDC) that has never existed. The process of transition from a steady state to a steady state in which the home country issues a central bank digital currency (CBDC). CBDC provides households with a highly liquid, convenient way to pay without storage costs, thereby reducing the market power of banks in deposits. In steady state, CBDC significantly improves social welfare and does not disintermediate the banking industry. However, during the transition to a new steady state, reasonable macroeconomic volatility will increase. Excessive demand for CBDC and currency squeezed out bank deposits, leading to an initial decline in investment, consumption and output. The authors use a nonlinear solution with occasional constraints to explore how easing policy reduces volatility during the transition period, comparing the effects of limits on nonresidents, constrained caps, tiered remuneration, and central bank asset purchases. The constrained cap most effectively reduces disintermediation and output losses during the transition period, with its optimal level being approximately 40% of steady-state CBDC demand. The Institute of Financial Science and Technology of Renmin University of China compiled the core part of the research.

Non-technical summary

A large body of academic literature has studied CBDC As a monetary instrument spreads in a new equilibrium state. In this article, the authors look at the issue from a different perspective, examining the long-term macroeconomic impact of CBDC from the moment of its initial launch until it is firmly established as a payment instrument.

The author's main concern is what policies can help balance the trade-offs in the transition phase: on the one hand, the excessive demand for CBDC and the The risk posed by macroeconomic and financial stability, on the other hand, is the welfare loss caused by excessive restrictions on the demand for CBDC, resulting in an excessive reduction in the monetary instruments available to households.

The author establishes a two-state country considering financial frictionsDS TheGEmodel studies the transition process from the steady state without CBDC to the issuance of CBDCby the home country. Households need liquidity to finance transactions, so they hold funds in the form of cash, bank deposits or CBDC. Deposits are paid, cash and CBDC are not. Unlike deposits and CBDC, cash requires storage costs. Households value that CBDC provides a variety of available monetary instruments, but its marginal utility decreases with the amount of each monetary instrument held. The authors assume that banks have monopolistic market power in the deposit market. As monopolies, banks set deposit rates lower than lending rates because deposits provide liquidity services. After the launch of CBDC, the monetary instruments available to households have increased. In order to curb the outflow of deposits, banks will increase deposit interest rates. Therefore, the availability of CBDC reduces the market power of banks and may lead to an increase or decrease in deposits.

Comparing equilibria with and without CDBC, the authors find that when CBDC is available, both deposit rates and deposits increase, and both domestic and foreign output increase slightly. Welfare would also improve, although the impact on foreign economies would be more limited. Next, the authors perform a nonlinear solution of the model to study the transition between the two steady states. For CBDC demand at low steady-state conditions (5% of steady-state output in the authors’ simulations), the introduction of CBDC has no substantial impact on the macroeconomy. For CBDC demand in the high steady state (30% of steady state output in the authors' simulations), the transition to the new steady state is characterized by large fluctuations in CBDC, cash, and deposits, resulting in lending rates, investment, and consumption fluctuations. In the short term, demand for CBDC and cash surges beyond new steady-state levels, crowding out bank deposits and triggering a decline in investment and consumption. Output will decrease initially and then gradually rise back to a new steady-state level after the initial volatility subsides. Applying this model in and estimating it under two steady-state demand calibrations, a rough calculation shows that a limit of about 3,000 euros per person can effectively control excessive demand.

The authors explore how to reduce volatility during the transition period using several different tools: first, setting soft and hard holding limits; second, implementing A tiered CBDC remuneration scheme that imposes negative interest rates on CBDC holdings above certain limits to penalize “excessive” holdings; third, the imposition of limits on CBDC holdings by non-residents that either prevent non-residents from holding CBDC, or lead to non-residents facing higher costs in CBDC cross-border transactions. In addition, the authors also examine whether it is effective for central banks to purchase private sector assets to balance the issuance of CBDC. Ultimately, it was found that binding caps are most effective at reducing disintermediation and output losses during the transition period and minimizing international spillovers, with the optimal level—i.e., minimizing welfare losses—approximately steady-state CBDC demand 40%.

1. Introduction

Participating in international More than 90% of central banks surveyed in a recent Clearing Bank survey said they were involved in CBDC efforts. Major central banks, including the People's Bank of China, are seriously studying this issue: the People's Bank of China is conducting an electronic renminbi pilot with more than 200 million test users; the Bank of England emphasized the possible need for a digital pound in the future in the summer of 2023; the European Central Bank in 2023 A two-year preparation phase was launched in October to prepare for the possible launch of a digital euro.

A large body of academic literature has examined the various potential impacts of CBDC on banks, the broader financial sector and other economic sectors, as well as the impact on international spillovers. These papers all focus on the impact of CBDC on the economy under steady state conditions. In this article, the authors look at this issue from a different perspective and examine the macroeconomic impact of CBDC in the transition to steady state.

The author's motivation for raising this question is the novelty of CBDC as an additional (yet non-existent) payment method. Because the extent of CBDC adoption is uncertain, there is considerable uncertainty about its potential impact at launch and during the transition to a new equilibrium. Estimates of potential demand for CBDC range widely. While at the lower end of the estimated range it may not pose significant challenges to banks, at the upper end it could disrupt the financial sector, especially if introduced quickly (Bank of Canada et al., 2021; Bank of England, 2023). Replacing CBDC holdings with bank deposits may lead to an increase in bank financing costs, thereby potentially adversely affecting credit, investment, and ultimately the entire economy.

For this reason, different mechanisms to limit the demand for CBDC have been proposed to curb the imminent risks to financial stability due to the introduction of CBDC, such as Bindseil ( 2020) discussed holding caps and tiered compensation plans to control the amount of CBDC. Importantly, these measures are also mentioned in the regulatory proposals for the establishment of a digital euro, which envisage that “the European Central Bank should develop tools to limit the use of the digital euro as a store of value and determine its parameters and manner of use”. The Bank of England (2023) explicitly considers limiting holdings of the digital pound during the transition period following its launch, to limit bank deposit outflows and allow UK authorities to understand more about its implications.

Therefore, how to optimally manage CBDC during the transition to a stable state remains an open question. In a typical macroeconomic setting, any limit that keeps CBDC holdings below optimal steady-state values reduces welfare. However, during the transition from steady state without CBDC to stability with CBDC, there may be reasons to impose restrictions, especially as the transition period may involve a severe overshoot of CBDC demand and increase macroeconomic volatility. International linkages are another complicating factor: while central banks are developing retail CBDCs for domestic use, residents in, for example, unstable economies may decide to hold foreign CBDCs as a store of value, creating potential cross-border spillovers. effects and spillover effects.

Following Andolfatto (2021) and Niepelt (2023), this article assumes that banks have monopolistic market power in the deposit market but act as price takers in the loan market Or, in the loan market, monitoring costs will generate financial accelerator mechanisms, as described by Bernanke et al. (1999). As monopolies, banks set deposits below the final lending rate, which households accept because of the liquidity services the deposits provide. To control deposit outflows when CBDC was introduced, and as the monetary instruments available to households expanded, banks raised deposit rates. Therefore, the availability of CBDC reduces the market power of banks, potentially leading to an increase or decrease in deposits.

2. Model

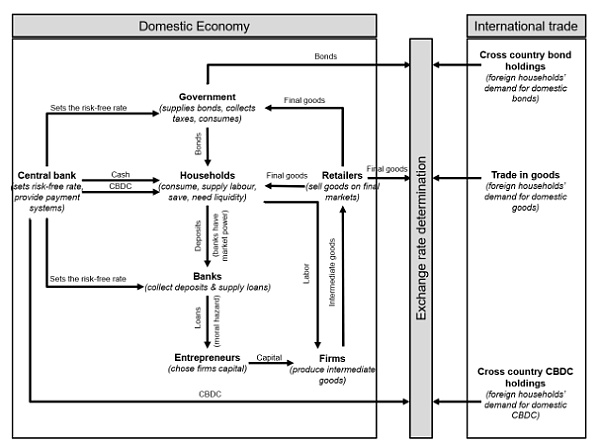

This model expands Ferrari Minesso (2022) added the conditions of financial friction and occasional constraints, and used a nonlinear solution method to study the transition dynamics from the steady state without CBDC to the steady state with CBDC. Figure 1 provides an overview of the model setup from the perspective of the national economy and depicts the interactions between the different agents in the model.

Figure 1: Model overview

There are two corresponding Economies (domestic and foreign) that trade goods and financial assets (bonds). Bond markets are incomplete, so unsecured interest parity (UIP) does not hold. Consumers provide labor to firms, save and consume final aggregate goods, and they also need liquid assets to purchase final goods. Households can invest in three financial assets: currency, bonds, and deposits. Currency can be used for payment, but is free, and storage costs increase linearly. Bonds are also traded internationally, but are paid and cannot be used for payment. Deposits are paid and can be used for payments, although they may not provide the same degree of liquidity services relative to cash. Since deposits provide liquidity services to households, banks can earn rents from issuing deposits, so the return on deposits is lower than the risk-free rate, as Andolfatto (2021) states. The computational complexity of the nonlinear solution model relies on the Constant Elasticity of Substitution (CES) aggregator to define demand for payment instruments and keep them operational. For example, Ferrari Minesso et al. (2022) and Assenmacher et al. (2023) show how liquidity needs can be micro-funded through preferences for anonymity or decentralized markets.

The financial sector consists of finite-life banks that combine net assets and deposits to provide loans to businesses. Suppose there is a financial friction similar to the "financial accelerator" mechanism described by Bernanke et al. (1999) and Christensen and Dib (2008). Specifically, assume that banks cannot costlessly observe the outcomes of corporate investment projects. Because of this friction, highly leveraged entrepreneurs have incentives to misreport their firm's performance and default on their debts. As a result, banks charge higher interest rates on highly leveraged firms, which makes credit spreads countercyclical relative to the risk-free rate. As noted above, banks also have market power in setting deposit rates, which are lower than lending rates because deposits provide liquidity services to households.

The productive sector of the economy consists of three different types of firms: capital goods producers, intermediate goods producers, and retailers. Thecapital goods producers are conceived as a series of identical enterprises that use undepreciated capital and a portion of final goods to produce new capital goods. Entrepreneurs combine their net worth and bank loans to purchase new capital goods, which are used along with labor to produce final undifferentiated goods. Entrepreneurs accumulate profits but have an exogenous probability of exiting the market in each period. The final goods are packaged and sold by retailers to domestic and foreign consumers. Adopt the Calvo pricing model and assume that the final commodity price is not completely flexible. The model is closed with a public sector that determines public spending and a central bank that sets nominal interest rates using the Taylor rule.

Importantly, this articleassumes that in addition to cash, the country’s public sector can also issue CBDC . CBDC is a central bank liability that households can directly access and use for payments. Under standard circumstances, CBDC does not pay interest. By introducing CBDC as an alternative payment instrument, liquidity constraints on households are relaxed and banks extract less rent from deposits. Additionally, CBDC can be traded between countries, subject to certain restrictions that will be discussed below. It is a digital payment instrument that, unlike cash, is not subject to storage costs. Following Brunnermeier and Niepelt (2019), this article assumes that the issuance of CBDC is “monetary policy neutral”—that is, the management method will not change the distribution of credit in the economy. In this way, the aggregate output and welfare effects generated by CBDC issuance are not affected by the way the central bank expands its balance sheet, but are driven by economic fundamentals, such as the marginal productivity of production factors, aggregate demand, and the availability of capital. Adalid et al. (2022) show that this assumption is consistent with the current composition of liabilities in the European system.

Next, this article will introduce the issue from the perspective of the domestic economy.

Omit the model construction part of this article, see the original text for details.

3. Simulation

In this paper In this section, the author introduces the steady-state effects without CDBC and with CDBC and the transition process between the two steady states. To account for the nonlinearity of the transition between the two steady states and the presence of mitigation strategies, the authors use a global solution method to calculate the transition path. Studying this transition is crucial because in the long run (i.e., in the new steady-state equilibrium), having a CDBC may be efficient, while excessive demand for CBDC during the transition period may deintermediate the banking system and thereby In the short run, it leads to declines in credit, output, and welfare.

This model refers to the practices of Ferrari Minesso et al. (2022), Christiano et al. (2014), and Gertler and Karadi (2011). The discount factor satisfies that one period corresponds to one quarter. The parameters for the foreign country are calibrated based on data from the United States, while the parameters for the home country are set based on data from Germany, the largest economy in the euro area (Eichenbaum et al., 2021).

3.1 Steady-state effect

First consider the situation without supply How releasing CBDC with restrictions changes the new steady state compared to the steady state without CBDC. Assume that CDBC has no remuneration, monetary policy is neutral, foreign households can use it, and cross-border transaction costs are small.

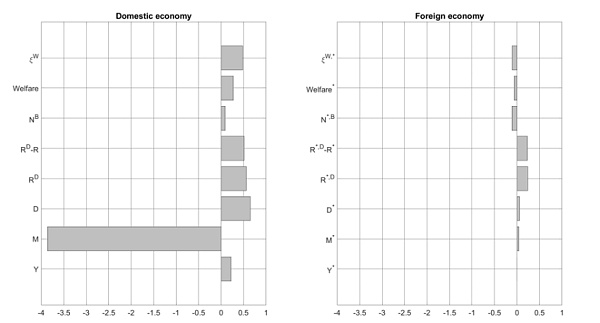

Figure 2 shows the percentage change in the stochastic steady state after the issuance of CBDC. In the domestic economy (left chart), output remains largely stable because in the configuration considered, CBDC does not increase capital and labor productivity in the productive sector, which ultimately determines steady-state output. There is a slight increase in welfare, about 0.3% of steady-state consumption, which can be captured by the consumption equivalence measure. The financial impact of CBDC is even more obvious. CBDC expanded the choice of payment instruments, attracting households, and cash demand fell by approximately 4%. In addition, banks’ monopoly power over the issuance of deposits is partially lost, which is challenged by CBDCs. As a result, banks need to increase the interest rates they pay on deposits to retain or attract customers, which has risen by roughly 0.5 percentage points. Endogenous increases in deposit returns increase total deposits by more than 0.5%. On a net basis, this is good for banks, as losses on the intensive margin (i.e. higher interest rates on deposits) are offset by gains on the broad margin (more deposits allow more loans to be made, which in turn leads to higher profits) offset. As a result, output improved slightly as more investment opportunities were financed.

In foreign economies, the introduction of CBDC has no or only marginal impact, but deposit interest rates will increase. The reason is that although CBDC does not bear interest in the baseline configuration, it will increase the risk of foreign households being affected by exchange rate valuations. Therefore, bank deposit rates need to increase endogenously in order for households to choose between holding CBDC or bank deposits.

Figure 2: Percent change between stochastic steady state without CDBC and with CDBC

3.2 Transition without mitigation policies

3.2.1 Reference standards

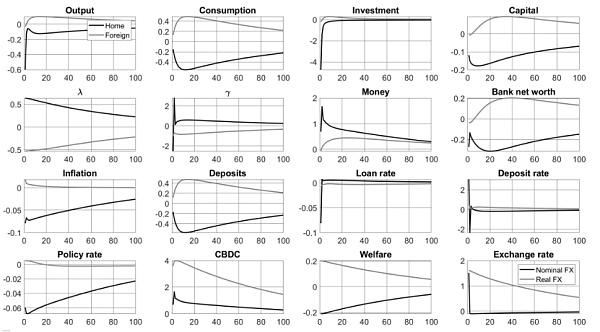

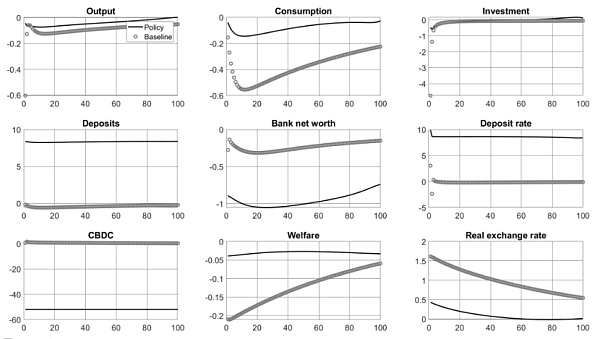

Consider first a transition without easing policies. Figure 3 reports the transition paths from the steady state without CBDC to the steady state with CBDC for the domestic economy (solid black line) and the foreign economy (solid gray line). The variable is expressed as a percentage deviation from the CBDC’s new steady state. If the new steady state is higher than the steady state without CDBC, the starting point of the simulation will be negative. After the issuance, domestic economic demand for CBDC exceeded the new steady state by nearly 2%. Households substituted CBDC for deposits, thereby reducing the credit available to businesses, triggering a decline in investment and capital in the economy. As investment falls, domestic output shrinks by about 0.6% relative to the new steady state, reducing consumption, prices and welfare. The country's central bank responded by lowering interest rates, causing the currency to depreciate. Most of the output losses during the transition period are absorbed relatively quickly, while CBDC demand takes more time to adjust to new steady-state levels; therefore, consumption, capital, and bank deposits take more time to reach the new equilibrium .

Figure 3: Transition to a new steady state without moderation

3.2.2 Lower steady-state demand for CBDC

The steady-state demand for CDBC is an important factor during the transition period. If steady-state demand is low, the introduction of a CDBC will not materially change deposit demand during the transition period. Therefore, macroeconomic changes should be limited.

As shown in Figure 4, if the demand for CDBC is low in the steady state, deposit outflows are limited to 0.1% of the steady-state level instead of 0.5% in the reference standard. Lower steady-state demand for CBDC also results in lower excess demand for CBDC during the initial phase of the transition, around 0.25% of steady-state levels, rather than the reference standard of 2%. All in all, the limited impact of CBDC on households' choice of monetary instruments means that credit supply does not take a material hit during the transition, so investment remains more stable and the contraction in output is negligible (about 0.1% of the steady-state level, or less than the reference 6 times lower than the standard).

Figure 4: Transition to the new steady state when CBDC demand accounts for 5% of the new steady state GDP and there are no easing policies

3.2.3 Higher capital storage costs

In the steady state, cash Demand may also change the trade-offs between different payment instruments. Figure 5 shows the transition dynamics assuming currency holding costs of both countries are 10%. Under the new calibration, at steady state, money demand falls by about 35%, to about 20% of GDP. Correspondingly, demand for deposits and CBDC increased by 1.5 and 1.2 percentage points respectively. Output losses and excessive demand for CBDC are consistent with the reference standard model. Since the cost of holding money is higher under this calibration, there is a stronger rebalancing of non-monetary assets. Households therefore choose to liquidate currency holdings in order to acquire other types of assets during the transition period. However, because money accounts for a relatively small share of households' liquid asset portfolios, this stronger asset rebalancing changes little compared to the standard output effect.

Figure 5: Transition to a new steady state when the currency holding cost is 10% and there is no easing policy

3.3 Holding restricted transitions

Now return to the reference standard and consider introducing two different calibration limits. First, a soft limit is set on the level of CBDC demand in the steady state, aiming to prevent overreaction during the transition to the new steady state. Secondly, a more stringent restriction is set, that is, under steady-state conditions, the issuance of CBDC must not exceed 50% of its demand to further control demand. This tighter restriction will continue until the economy approaches its new steady-state level, i.e. until the 100th period, after which it will be gradually relaxed.

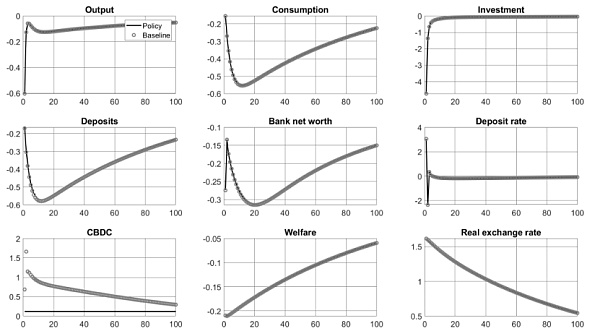

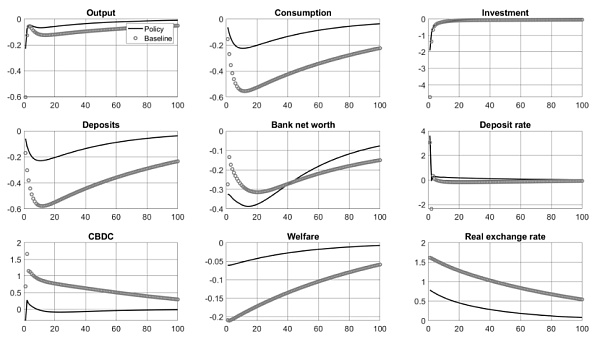

Figure 6 shows the transition situation under soft constraints. The solid black line represents the transition path of the home economy when there are soft constraints (modeled as constraints that are intermittently in effect), while the gray points represent the transition case without constraints. Essentially, the process of transitioning to a new steady state is similar whether there are soft limits or not; if there are differences, they are insignificant.

Tighter restrictions can prevent output losses during the transition period, as shown in Figure 7. The demand for bank deposits is no longer squeezed by excessive demand for CBDC, and the initial output loss is reduced to almost zero, while the amount of deposits has even increased. Investment remained stable and loan supply was little changed, as rising household deposits offset declines in bank net assets during the transition period. Overall, tighter constraints limit excessive demand for CBDC, prevent the disorderly withdrawal of bank funds, and stabilize the supply of credit.

Figure 6: Transition to a new steady state under soft holding restrictions

Figure 7: Transition to new steady state when holding limit is set to 50% of CBDC steady-state demand

< strong>3.4 Stratified remuneration transition

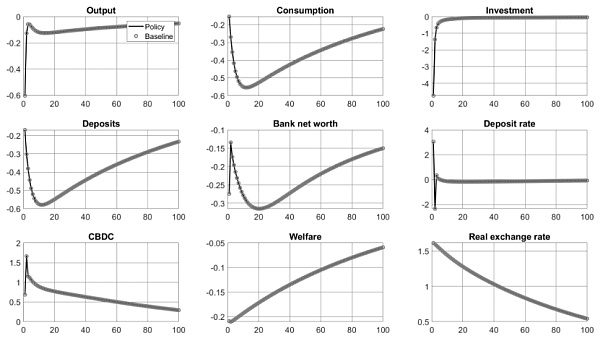

The tiered remuneration plan can also effectively smooth economic changes during the transition period - provided that the punitive interest rate is extremely High; see Figure 8. Assuming that CBDC holdings above 50% of steady-state demand will bear a negative interest rate of 300 basis points (while holdings below 50% of steady-state demand will not be paid), this will lead to significant excess demand for CBDC during the transition period decline. Therefore, domestic households are less likely to use CBDC to replace deposits, which reduces bank disintermediation and the negative impact on domestic investment, consumption and output. A higher penalty rate (500 basis points) would make these effects stronger and even expansionary. Households' aversion to CBDCs increases to the point where they turn to deposits, which in turn boosts investment and output growth.

Figure 8: Transition to a new steady state under stratified rewards

3.5 The transition of central bank balance sheet expansion

Figure 9 shows the transition of central bank purchases of bank loans to balance CBDC demand. This policy significantly reduced output losses relative to the no-policy reference, particularly through contraction in private investment—by about two-thirds. Central bank purchases replace lending by the banking sector, maintaining the supply of credit to the private sector, as described by Brunnermeier and Niepelt (2019). As investment remained more stable, the contraction in output was smaller and consumption remained at higher levels (i.e. the decline in consumption was reduced by two-thirds relative to the transition without easing policies). As a result, the economy contracts less and policy rates remain higher than in the baseline scenario. However, this policy was not as effective as quantitative restrictions in preventing the decline of bank intermediation. This reflects the fact that central bank purchases replaced the supply of credit to businesses by banks; however, households continued to liquidate deposits as they purchased almost the same amount of CBDC from the beginning of the transition as in the reference standard simulation.

Figure 9: Transition to a new steady state as central bank balance sheets expand

3.6 Transition in which foreigners’ access to CBDC is restricted

During the transition process of the domestic economy, restricting foreigners’ access to CBDC It does not effectively make it smoother, whether it is to completely prohibit foreigners from using CBDC (as shown in Figure 10), or to partially restrict foreigners' use of CBDC by increasing cross-border transaction costs (as shown in Figure 11).

The reason is that in this model, restricting the use of CBDC by foreigners does not affect the key mechanism that causes the domestic economy to lose output during the transition period-namely, in the domestic economy In the economy, the substitution effect of CBDC and domestic deposits exceeds the endogenous increase in deposit interest rates in order to attract or retain savers. This process mainly occurs within the domestic economy and is basically not affected by foreign countries.

Figure 10 : Transition to a new steady state when foreigners cannot access CBDC

Figure 11: Transition to a new steady state with foreigners partially accessible to CBDC (higher cross-border transaction costs)

3.7 Optimal levels of holding limits

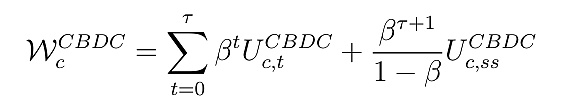

The above results suggest that holding limits are managed during the transition to a new steady state CBDC is very effective in terms of its effects. These restrictions balance the risk of a decline in the intermediation role of banks if demand for CBDC is too strong against the welfare loss of reduced household payment options if demand for CBDC is too restricted. This section will determine the holding limit level that maximizes welfare during the transition period relative to the equilibrium state without CBDC. Benefits during the transition period have two components. The first part captures welfare gains or losses during the transition period, and the second part defines (permanent) welfare in the new steady state in the absence of other shocks:

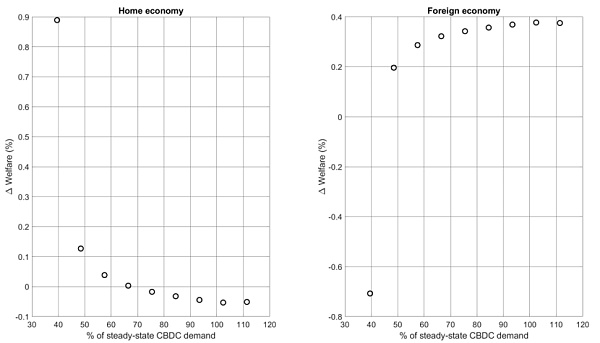

Figure 12 shows that during the transition period, according to different The percentage change in welfare at the holding limit level (expressed as a percentage of steady-state CBDC demand) relative to the steady-state situation without CBDC. When the holding limit exceeds 70% of the steady-state CBDC demand, there is a slight net welfare loss. This is because the welfare cost (the first part of welfare) caused by the increase in the volatility of macroeconomic variables during the transition period is still smaller than the welfare gain (the second part of welfare) brought by the availability of CBDC at this level. When the holding limit falls below 60% of steady-state CBDC demand, the net welfare benefit becomes positive and reaches a maximum at approximately 40%. Applying this setting to the euro area, the results suggest that a limit of approximately €3,000 per person would help effectively control excess demand.

Figure 12: Welfare gains (or losses) under different CBDC holding limit levels

4. Conclusion

In this paper, the author develops a two-country dynamic stochastic general equilibrium including financial frictions ( DSGE) model to study the transition process from a steady state without CBDC to a steady state with domestic issuance of CBDC. The study found that CBDC clearly improves welfare while not disintermediating the banking sector. In the new steady state, the amount of deposits increases as banks endogenously raise deposit rates. The impact during the transition period depends largely on unobservable CBDC steady-state demand. For low steady-state CBDC demand, the introduction of CBDC has no substantial macroeconomic impact during the transition period. But for higher steady-state CBDC demand values, simulations point to increased macroeconomic volatility during the transition period. This higher demand is less likely for a digital euro, as “waterfall” and “reverse waterfall” features would allow citizens to pay for purchases above holding limits, but the study found that policy could also mitigate these effects. A binding cap is most effective at reducing disintermediation and output losses during the transition period, with an optimal level of around 40% of steady-state CBDC demand.

These findings have implications for future research. Specifically: How long will it take to transition to a stable CBDC equilibrium state, by which time its benefits to the economy are fully realized? What factors determine the length of the transition period? How to shorten the transition period? These are questions worth exploring in future research to inform central banks when considering whether to issue a CBDC, but also to serve as a reference for the wider public.

Spain strategically positions itself within the realm of the digital euro, signaling a transformative trajectory for the financial landscape.

Hui Xin

Hui XinA final decision is yet to be made about the issuing of a digital euro by the European Central Bank (ECB).

Others

OthersThe Digital Euro Association (DEA) has published a new whitepaper

Bitcoinist

BitcoinistThe Italian Banking Association (ABI) expressed its support with a new position paper.

Ledgerinsights

LedgerinsightsThe Commission plans to propose legislation for a ‘possible’ digital euro in 2023 to enable parliament and the European Council to debate it.

Others

OthersA leaked paper written by France, Germany and Italy, seen by CoinDesk, seeks to guide the European Central Bank’s plans for the digital currency

Others

OthersCommenting on the recent market volatility, Fabio Panetta also said stablecoins were still “vulnerable to runs,” just as investing in cryptocurrencies carried certain risks.

Cointelegraph

CointelegraphJonas Gross spoke with Cointelegraph about the digital euro’s risks for private banks and the goals of the ECB.

Cointelegraph

CointelegraphFindings from the ECB's focus groups said the public was more likely to accept a digital euro that is accepted in physical and online stores and allows easy person-to-person payments.

Cointelegraph

CointelegraphThe commission will consult with industry specialists on issues concerning the digital euro including international payments, privacy and the impact on financial stability.

Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph