Author: Shlok Khemani, michaellwy Source: Decentralised.co Translation: Shan Ouba, Golden Finance

Last week, the world was stunned by the image of Mechazilla aboard a booster rocket after its successful mission to space. This is an era in which artificial intelligence has taken over the public mind. Nvidia's share price performance over the past few months has been reminiscent of the companies that added blockchain to their names during the frenzy of 2021. This time, though, the hype has substance. Artificial intelligence, as a field, has been attracting a lot of attention, capital, and talent.

Blockchain (or cryptocurrency) as an industry, by contrast, has lost its way in a world filled with jargon and meme assets. It's hard not to feel like continuing to develop in this industry is a waste of time. There are definitely bull rallies from time to time, and prices (or markets) are an important factor in keeping people working in the industry. We are either at the forefront of the evolution of the internet, or we are in the middle of a massive psychological experiment examining what happens when individuals can turn anything into a market.

Or maybe both.

Today’s post, written in collaboration with Michael from Monad, explores a simple question. Why are blockchains important? Are they as important as space exploration or artificial intelligence as an innovation system? Are we wasting our time? To find the answer, we drew comparisons to history. Specifically, to the history of the automotive industry.

Ford vs. Toyota

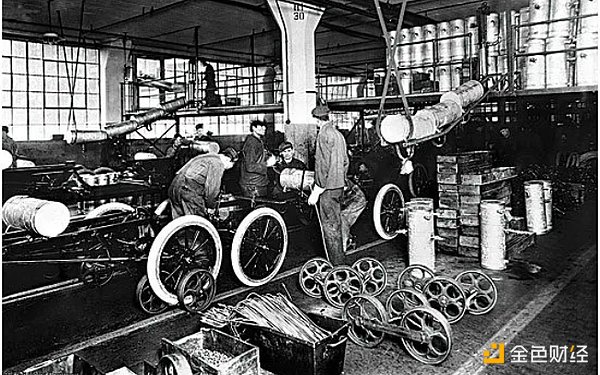

Before Henry Ford founded the Ford Motor Company in 1903, cars were a luxury that only the wealthy could own. Cars were often built by hand, with low productivity and limited skilled labor. Ford’s genius was to move manufacturing to a moving assembly line, with each worker performing a specific task as the cars rolled by. By breaking jobs down into simple, repeatable operations, Ford could employ less-skilled workers to perform many tasks. This greatly increased productivity, reduced costs, and made cars affordable to the middle class.

Mass car ownership changed society in many ways. Horse-drawn carriages, once the primary form of transportation, quickly became obsolete. People could travel farther for work and leisure. Countless new jobs emerged, not only in the auto industry but also in supporting industries such as rubber, steel, and oil. Roads reshaped the landscape, while modified Fords served as tractors, increasing agricultural productivity.

Ford’s rise marks a distinct “before and after” moment in human history.

About 50 years later, after World War II, Japanese automaker Toyota was on the verge of bankruptcy. The government refused a bailout, 1,600 workers were laid off, and founder Sakichi Toyoda resigned. Only an order from the U.S. military for vehicles for use in the Korean War kept the company afloat. Around this time, Eiji Toyoda (the founder’s cousin) and Taiichi Ohno began to reimagine automotive assembly line operations. Inspired by American supermarkets, they introduced systems such as just-in-time, lean manufacturing, and Kanban.

Andons (problem display boards) light up at Toyota factories to notify workers of abnormal conditions

These changes made Toyota more efficient, more productive, and less expensive, while also improving the quality of its vehicles. The once bankrupt company grew into one of the world's largest automakers and earned a reputation for reliability.

Over time, the "Toyota Way" became the standard for operations in the auto industry and all industries - from healthcare and retail to chip manufacturing and software development. While Toyota’s rise may not have been as sudden or dramatic as Ford’s, it has changed the world in a subtle, gradual, but profound way.

Innovation comes in many forms.

The Schumpeterian view, derived from the work of economist Joseph Schumpeter, argues that innovation is the primary engine of economic growth. Schumpeter coined the concept of “creative destruction,” which describes the process by which new technologies and innovations disrupt and replace obsolete ones, thereby driving economic progress.

In simple terms, these are the breakthroughs that came before and after that have multiplied human productivity and unlocked enormous potential economic value. These include Henry Ford’s assembly line, the printing press, the microprocessor, the internet, and artificial intelligence.

In contrast, the Coasean view is rooted in the ideas of economist Ronald Coase and focuses on transaction costs and the role of institutions in mitigating those costs to facilitate economic activity. Coase argued that economic institutions and institutions exist primarily to minimize transaction and coordination costs between individuals and organizations.

The Coasean perspective draws attention to the less obvious but equally important infrastructure that supports economic efficiency. Improving these institutional frameworks can lead to significant economic gains, even though those benefits may not be immediately apparent. DAOs may be a good example of a Coasean innovation.

Toyota’s manufacturing innovations initially transformed the company’s fortunes, then changed the economics of the auto industry, and ultimately affected all industries. However, the transformation occurred gradually, and its effects were only apparent in retrospect, not during the transition.

Other advances, such as double-entry bookkeeping, stock exchanges, open source software, and reusable rocket boosters, are examples of technological progress in the Coasean sense. While these innovations may not be as dramatic as those in the Schumpeterian sense, they improve economic efficiency and advance human progress in equally important ways.

So what about cryptocurrencies?

Consider the areas where cryptocurrencies have found product-market fit or are about to find product-market fit.

First, Bitcoin has grown into a trillion-dollar asset and established its position as a legitimate, institutionalized store of value. It has most of the properties of gold — scarcity, durability, portability, divisibility, and inertness. Time will tell whether it surpasses gold as the de facto store of value. If so, it will be thanks to the fact that it achieves these properties more efficiently. It has its own ETF. At least Wall Street thinks it’s an asset worth watching. Next up are stablecoins, which offer a cheaper and faster way to make cross-border payments than traditional methods. There is a huge demand for them. The growth of the total supply of stablecoins from $500 million to $168 billion is proof of this. It’s worth thinking about why this is the case. Fiat money transfers from one country to another involve a range of intermediaries, such as banks, governments, and providers like Western Union. Each of them exists to provide a layer of trust service and charges a fee (in the form of money or time) for doing so. Blockchain, as a highly secure, transparent, and decentralized ledger, reduces the cost of trust exponentially. Stablecoins are cheaper and faster because the Ethereum blockchain has as much trust as the institutional stack that fiat currencies rely on (in fact, more than they do). The same applies to areas like decentralized finance (DeFi) and digital art (NFTs). In DeFi, interacting with smart contracts is more efficient than dealing with intermediaries like banks, brokerages, and exchanges. Before NFTs, auction houses acted as trust intermediaries between collectors and artists. An unknown artist couldn’t sell a piece of art for $100,000 without the approval of the auction house. Ethereum again provides similar (or even better) trust guarantees, but faster and cheaper. Recently, we’ve seen the emergence of various DePIN networks. Are these networks creating entirely new services? Not really. Mobile data, electricity, GPUs, satellite data, and digital maps exist independently of blockchains. However, their monetization and distribution economics are either inefficient or dependent on centralized institutions. The DePIN network is trying to implement a better form of coordination. Cryptocurrency is fundamentally a Coasean technology. Sure, when you analyze cryptocurrencies from a financial perspective, it does mark many before and after moments. But when you zoom out, you realize that finance facilitates human coordination and productivity. Finance itself is Coasean. Cryptocurrency will not change the world like AI or rockets. It was not meant to do those things. Instead, crypto can play a different role. It will help collect data to train our LLMs and provide AI agents with a means to transfer value between them. It will accelerate the rate at which new networks are formed. It might just help the next Elon Musk move from a third world country to the US. But in and of itself, crypto may not destroy the social fabric as we expect. It is the paint, not the canvas itself. What is painted with it remains to be seen. As technology continues to advance along an exponential trajectory, crypto will power its development, pave the way, and strengthen the bridges.

Encryption will change the world in its own way.

Miyuki

Miyuki

Miyuki

Miyuki Kikyo

Kikyo Kikyo

Kikyo Weiliang

Weiliang Alex

Alex Miyuki

Miyuki Weiliang

Weiliang Alex

Alex Catherine

Catherine Miyuki

Miyuki