Author: Preston Byrne, Partner at Byrne & Storm Law Firm; Translated by: 0xjs@Golden Finance

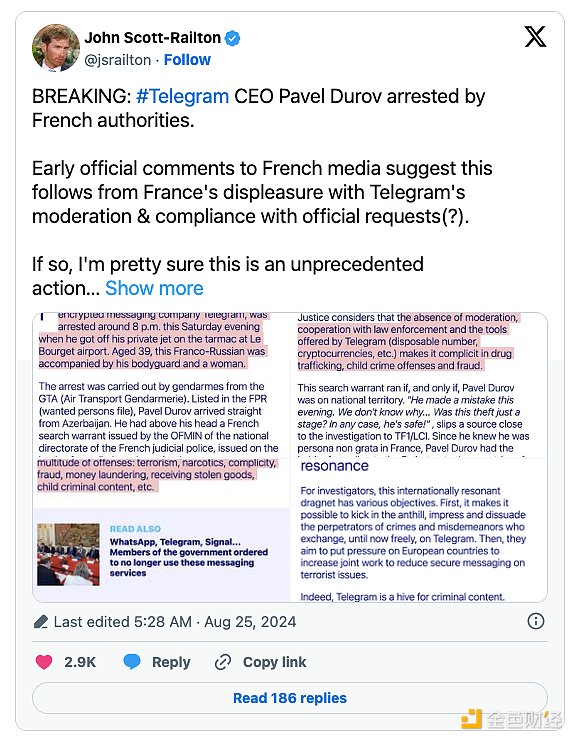

On August 24, Pavel Durov, founder of the popular messaging app Telegram, was arrested when his private jet landed in France.

Early signs suggest that the arrest stems from Telegram’s alleged non-compliance with French demands for content moderation and data disclosure:

Some legal background

Most non-Chinese social media companies with global influence are headquartered in the United States. This is not accidental.

The United States (wisely) took policy steps in the late 1990s to minimize liability for online service operators, most notably with the enactment of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. This act (essentially) holds social media site operators not liable for the tortious or criminal conduct of their users. Of course, there are some very narrow exceptions to this rule; for example, illegal pornography is subject to mandatory takedown and reporting regulations (see: 18 US Code § 2258A), and the passage of FOSTA-SESTA prohibits operators from providing services that involve sex trafficking or prostitution (see: United States v. Lacey et al. (Backpage), 47 US Code § 230(e)(5)).

Other than that, social media site operators are generally not liable for the tortious or criminal conduct of their users. If they were merely passively hosting the content, they would not be liable under the aider/abbet theory either. (See: Twitter v. Taamneh, 598 US _ (2023 ) – at least on this side of the Atlantic in the US, civil liability for aiding and abetting requires “knowing and substantial assistance,” while federal criminal liability – because Section 230 does not apply to state criminal laws – requires specific intent to assist in a crime).

This means that, if I use Facebook to organize a drug deal, Facebook (a) has no obligation to scan its service for illegal use and (b) has no obligation to restrict that use and generally cannot be subject to civil penalties for my misuse unless Facebook “materially facilitates” that illegal use, i.e., expressly encourages it (see, e.g., Force v Facebook, 934 F.3d 53 (2d Cir. 2019), in which Facebook was found not civilly liable under JASTA to Hamas victims who used Facebook to disseminate propaganda online; see also Taamneh, supra), and cannot be criminally liable (a) under state criminal § 230 and (b) under federal criminal law, so long as Facebook did not intentionally and knowingly aid, abet, counsel, or cause the commission of a crime, pursuant to 18 USC § 2.

Most countries don’t have such a permissive system. France is one of them. For example, the 2020 law against “hate speech on the Internet” (Loi Lutte Contra la Haine sur Internet) allows global internet companies to be fined $1.4 million per offense, up to 4% of their global revenues, for failing to limit “hate speech” (which is “protected speech” in the United States) on their sites. Similarly, Germany has its own law, the Network Enforcement Act (sometimes called the “Facebook Law” but often shortened to NetzDG), which mandates the removal of inflammatory political content or the government can impose fines of more than €50 million.

I’m not a French lawyer, so it’s hard to figure out exactly which legislative provisions are being invoked here. Charging documents or arrest warrants will tell us more once they are released. I’m pretty sure the US isn’t going to file a fine lawsuit against Telegram Messenger, Inc. under hate speech laws (like the EU DSA), because if it were us, Durov wouldn’t have been dragged off a plane in handcuffs. French outlet TFI Info, which reported the news, said the charges could be aiding and abetting, or conspiracy:

The Justice Department believes that the lack of auditing, cooperation with law enforcement, and the tools provided by Telegram (disposable numbers, cryptocurrency, etc.) make it an accomplice to drug trafficking… and fraud.

More information will be revealed after the arrest warrant is issued.For example, if it is found that Durov did actively help criminal users gain access to the platform, such as a drug addict writing to the support channel saying, “I want to sell drugs on your platform. How can I do that?” Durov responded by offering to help, then he would suffer the same fate in both the US and France.

However, if the French are simply saying that Durov’s failure to police his users or to respond to French document requests in a timely manner was a crime (which I suspect is the case), then this represents a dramatic escalation in the war on online censorship. It means that European countries will attempt to dictate beyond their borders what content foreign companies can and cannot host on foreign web servers.

If correct, this would be a sharp departure from the current approach taken by most US-based social companies to comply with US regulations, which generally dominates the global compliance strategy of most non-Chinese social media companies, including those that fully encrypt their services (among them Telegram, WhatsApp, and Signal). In short, these platforms believe that if they don’t intend to use their platforms for crime, they are unlikely to be criminally charged. Clearly, that is no longer the case.

Telegram is not the only company in the world that has used its social media platform for illegal purposes. It is well known that Facebook’s popular encrypted messaging app, WhatsApp, has been used for years by Afghanistan’s former non-state terrorist group and current rulers, the Taliban. This fact was widely known by NATO generals during the Afghan war and reported in the media, and even again in The New York Times last year:

About a month later, unable to contact his commander during a nighttime operation, security officer Inkayad reluctantly purchased a new SIM card, opened a new WhatsApp account, and began recovering lost phone numbers and rejoining WhatsApp groups.

Inkayad sat in his police station, a converted shipping container with a handheld walkie-talkie on top. He pulled out his phone and began browsing his new accounts. He pointed out all the groups he had joined: one for all police officers in the precinct, another for former fighters loyal to a single commander, and a third one he used to communicate with his superiors at headquarters. In total, he said, he had joined about 80 WhatsApp groups, more than a dozen of which were used for official government purposes.

Of course, the Taliban now controls the entire government of Afghanistan—all levels of it—and Afghanistan is an enemy of the United States, which is Facebook’s home country. If Facebook really wanted to prevent people like this from using their service, the most effective way would not be to play whack-a-mole with individual government employees, as Facebook did, but to ban Afghanistan’s entire IP range and all Afghan phone numbers, and disable domestic app downloads, which Facebook did not do. Facebook chose non-measures rather than measures of action.

Yet, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg lives comfortably on an estate in Hawaii, not in exile, and presumably has no arrest warrant out for him, while Durov clearly does. I concede that it is possible (even likely, given that Telegram’s operations team consists of only 15 engineers and about 100 employees worldwide) that Facebook could respond more quickly to the French judicial request than Telegram did. But when you run a globally accessible encrypted platform, it is inevitable — repeat, inevitable, absolutely certain — that criminal activity will occur beyond your vision or ability to control. If Telegram is charged with violating French law by failing to moderate (as media reports have suggested), then apps like Signal (which is clearly unable to respond to law enforcement requests for content data and has similar functionality to Telegram) are equally guilty, and no American social company (or its top leadership) that offers end-to-end encryption is safe. Do we really think Meredith Whitaker (Signal Chair) should go to jail if she decides to go to France?

Image licensed under Pixabay

There are still many problems. Right now, this does not look good for the future of interactive web services in Europe. American tech entrepreneurs who run services in accordance with American values (especially protecting free speech and privacy through strong encryption) should not visit Europe, should not hire in Europe, and should not host infrastructure in Europe until this situation is resolved.

French Aiding and Abetting

Updated 26 August 2024

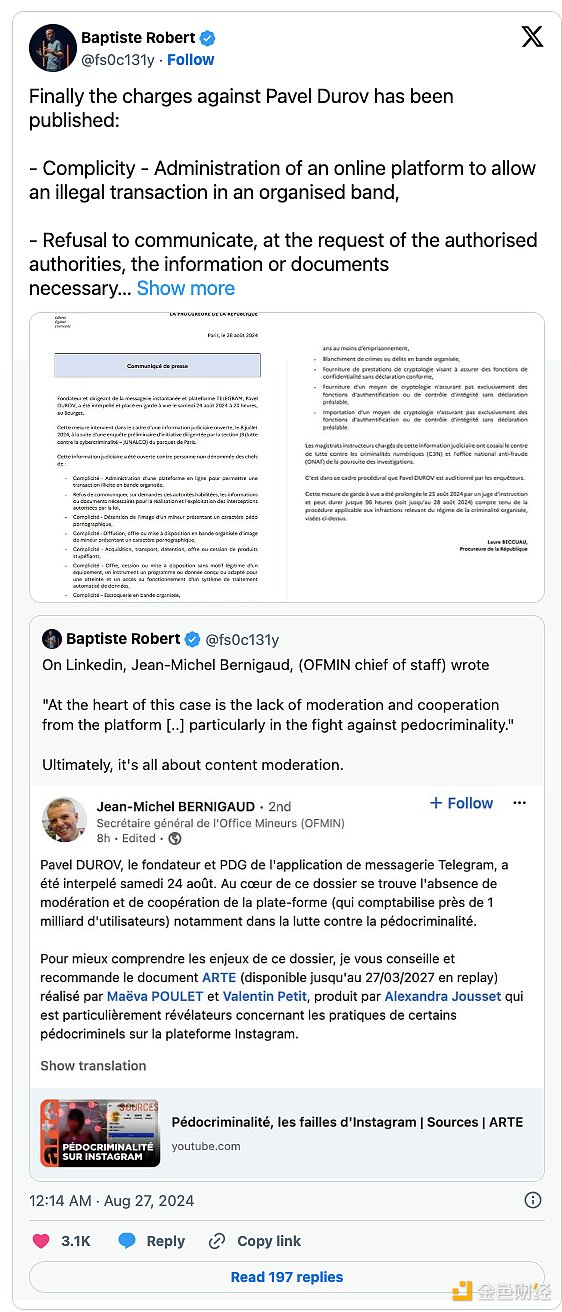

Mostly my hunch was correct:

There's a long list of crimes there. Most of them are related to the French crime of conspiracy, which is roughly equivalent to aider/abettor liability in the United States.

What’s important here is that in the United States, aider/abbettor liability requires a specific intent to cause a criminal result—that is, criminal conduct was the defendant’s purpose. The failure of U.S. social media companies to police their users does not rise to that level, which is why U.S. social media company CEOs are generally not arrested by the U.S. government for the criminal conduct of their users. In particular, CSAM charges would only rise to the level of a crime in the United States if Durov failed to comply with the U.S. notice-and-reporting regime for such content. The mere presence of criminal content without any notice does not give rise to criminal liability.

The French government has charged Durov with participating in (i.e., aiding and abetting) criminal activity, as well as with providing “encryption” software without a license, which must be approved by the government before use in France. The crimes he is accused of aiding include crimes roughly similar to the Racketeer and Corrupt Organizations Act, a compilation of crimes, money laundering, drugs, hacking, and providing unlicensed encryption technology.

In the absence of substantial evidence that Durov and Telegram explicitly intended to commit these crimes or cause them to occur (which is highly unusual for a social media CEO to do, especially since these crimes are illegal everywhere in the world, including in the United States, which has historically been very good at extraditing criminals), there is no reason why similar charges could not be brought against any other social media service provider in France with less than perfect moderation practices, especially one that offers end-to-end encryption.

We need to wait for the evidence to come in before we can draw any firm conclusions on this point. My guess, though, is that Durov was not “aiding and abetting” as the United States understands it, and that France decided to use different principles to try to regulate a foreign company that it believed had too lax moderation policies.

To summarize:

Currently, if you run a social media company or you provide encrypted messaging services that are accessible in France and you are based in the United States, then leave Europe.

Original link: https://prestonbyrne.com/2024/08/24/thoughts-on-the-durov-arrest/

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance Huang Bo

Huang Bo Edmund

Edmund Others

Others Others

Others Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph