Source: FEDS, Author: James A. Clouse

In January 2024, the Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C. released "A Field Guide to Monetary Policy in the New World of Central Bank Digital Currencies, Stablecoins, and Narrow Banks" (A Field Guide to Monetary Policy) at FEDS Implementation Issues in a New World with CBDC, Stablecoin, and Narrow Banks), which attempts to discuss the transmission impact of the structural evolution of financial markets on the implementation of monetary policy in the context of new policy tools, technological advances, and regulatory developments.

Based on previous research, the author of this article combines well-known scholars such as Tobin (1969) and Gurley and Shaw (1960) to analyze banks from the perspective of monetary theory and monetary policy. industry research, establishing a quantitative framework that can analyze the relationship between regulatory developments and the implementation of monetary policy in the banking and non-banking sectors. The framework describes a set of interrelated supply and demand curves for all financial instruments in a competitive model of financial markets and takes into account the portfolio allocation costs and balance sheet costs of financial intermediaries, with special discussion of central banks, both retail and wholesale. The impact of digital currencies (CBDC), stablecoins and deposits provided by narrow banks, and how these structural changes could affect interest rates and the size and structure of balance sheets. This article concludes that the introduction of new fixed-rate assets by the Federal Reserve or other financial intermediaries will have a significant impact on equilibrium interest rates and financial intermediation patterns, and may also affect the effectiveness of monetary policy tools. These effects are most pronounced when new financial assets are close substitutes for existing financial assets.

Benchmark model

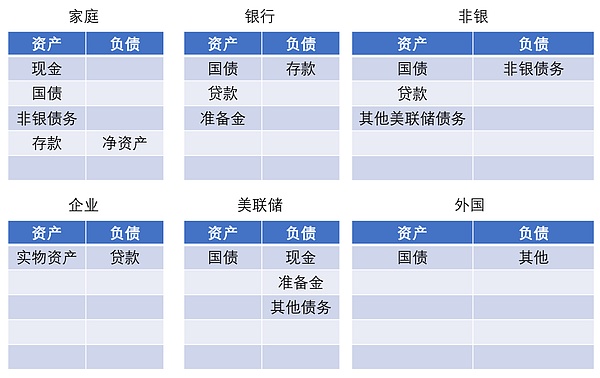

Based on the benchmark model of Chen et al. (2014) involving multiple sectors, including households, banks, non-banks, corporates, government and foreign sectors, the model proposed in this paper follows Tobin's (2014) 1969), based on a simple portfolio optimization framework, the demand for financial assets in each sector is derived. A key element of the framework is portfolio habits, which define baseline target asset and liability allocations for households and financial intermediaries. Households and financial intermediaries can deviate from these customary portfolio allocations, but doing so incurs portfolio costs. In addition to portfolio composition costs, financial intermediaries also face costs of increasing the size of their balance sheets.

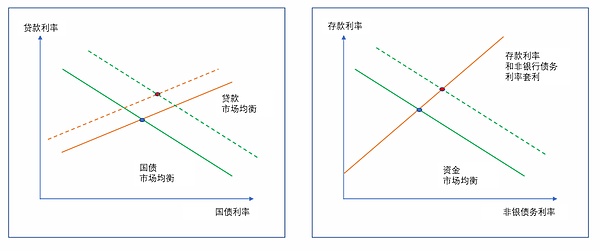

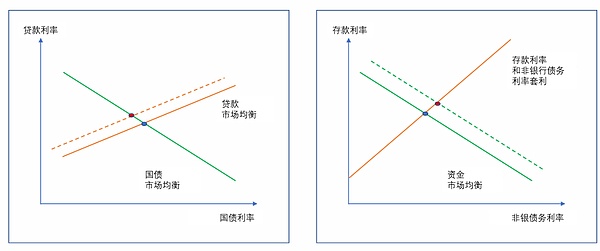

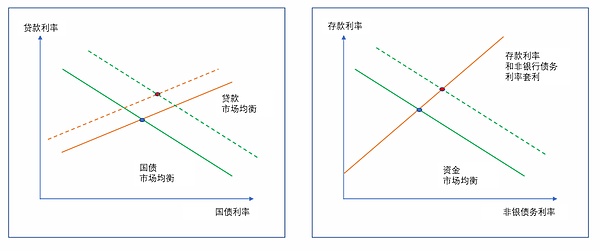

Exhibit 1 Financial market structure in the benchmark model

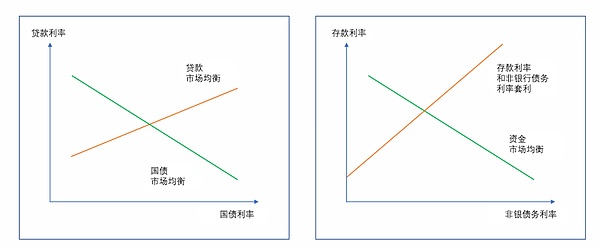

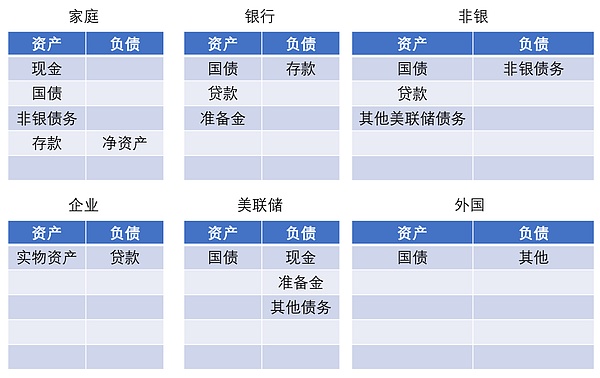

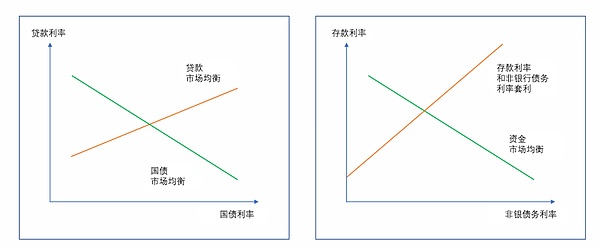

Described in this article The equilibrium interest rate can be simplified into two aspects: one describes the loan interest rate and Treasury bond interest rate combination that is consistent with the loan market equilibrium, and the other describes the loan interest rate and Treasury bond interest rate combination that is consistent with the Treasury bond market equilibrium.

As shown in the orange line on the left side of Figure 2, the loan market equilibrium curve is upward sloping (other conditions remaining unchanged, the higher the Treasury bill interest rate , meaning that the loan interest rate must be higher before intermediaries are willing to provide any given amount of loans). The equilibrium curve (green line) of the Treasury market is generally downward sloping (other conditions being equal, lower loan interest rates will lead to more borrowing in the loan market, and higher Treasury interest rates are needed to attract and clean up the Treasury market. additional funds required).

The equilibrium interest rates on deposits and non-bank debt can also be represented by the orange line on the right side of Figure 2 under the assumptions of the benchmark model. The spread between interest rates on deposits and rates on nonbank debt reflects the gap between the interest rate managed on reserves and the rates managed on other Fed liabilities, and also reflects the relative demand for deposits and nonbank debt by households. The funds market equilibrium relationship, the green line in the figure, describes the balance between households' desire to invest in deposits and non-bank debt and the supply of deposits and non-bank debt provided by banks and non-banks. The position of this curve is strongly influenced by the weighted average return on assets of banks and nonbanks, as well as the interest rates on assets competing with deposits and nonbank debt in households' portfolios.

Chart 2 Equilibrium in the baseline model

In addition, since households are assumed to Households have relatively strong habits in the financial assets they wish to hold, and household preferences largely determine the relative size of financial intermediaries. In particular, the relative sizes of bank, nonbank, and Fed balance sheets are driven primarily by the relative sizes of households' demand for deposits, nonbank debt, and physical money, respectively. The asset mix of banks and nonbanks largely reflects the habits of these sectors.

Three baseline model variants considering central bank digital currencies, stablecoins andnarrow banks

The first variant considers the inclusion of retail and wholesale central bank digital currencies. In this model, only households can invest in retail central bank digital currencies,while banks and non-bank financial institutions can invest in wholesale central bank digital currencies.

The second variant is to introduce so-called stablecoins into the model. Stablecoins are issued by narrowly defined non-bank institutions and are held only by households.

The third variant considersthe role of so-called narrow banks, which issue deposits and hold assets solely in the form of reserves.

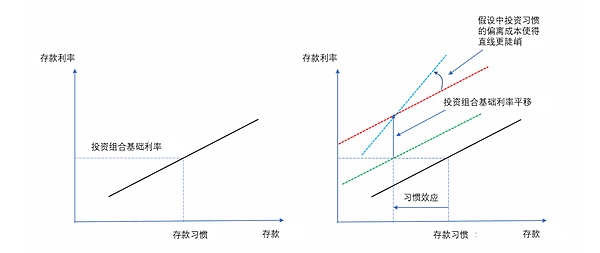

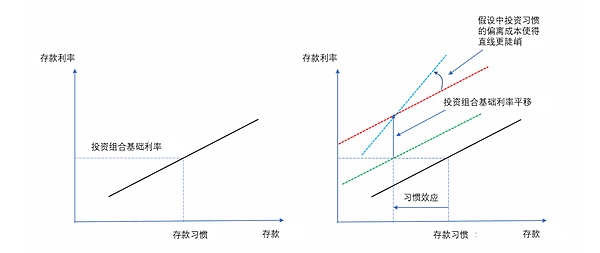

For example, Figure 3 illustrates the substitution effect on household deposit demand caused by the introduction of a new interest-bearing asset. The left-hand panel shows that the initial household deposit curve is upward sloping, with the deposit rate plotted on the vertical axis. When the deposit rate is equal to the portfolio reference rate, households' demand for deposits is exactly equal to the customary level of deposits. The right-hand panel shows the hypothetical impact of introducing a new interest-earning asset on this deposit curve. If new financial assets attract customary levels of demand at the expense of deposits, then the new customary level of deposits will fall, as shown by the movement of the black line toward the green line. If the new financial asset carries interest, the portfolio base interest rate will also change. The graph shows the impact when the portfolio reference rate rises from the green line to the red line. Finally, based on the authors' assumptions about the cost of deviation from habits, if the level of deposit habits decreases, the slope of the deposit line becomes steeper, as shown by the rotation from the red to the blue line. All these types of substitution effects play an important role in the model.

Chart 3 The impact of introducing new financial assets

Specifically, the article It is believed that central bank digital currency is a new financial asset, and the first variant of the benchmark model is studied. Retail and wholesale central bank digital currencies are respectively R_CBDC and W_CBDC. Among them, R_CBDC is only held by households and is a new financial asset that can be used as an investment tool. The Federal Reserve also has corresponding new liabilities. Assume that households have a "habit" to R_CBDC, similar to their "habit" to other financial assets. Introducing R_CBDC into the model also requires a new Fed liability management rate, ????_???????, which the article assumes to be zero to match the assumed interest rate for physical money and assumes that habituation to R_CBDC is initially complete At the expense of getting used to physical money, again, this article assumes that W_CBDC’s interest rate is set at a level comparable to reserves or other Fed liabilities held by financial intermediaries.

The article's findings show that all interest rates administered by the Fed - nominal rates on physical currencies, retail central bank digital currencies, reserves, other Fed liabilities and wholesale Interest rates on central bank digital currencies – and an equivalent increase in the equilibrium lending rate, resulting in a one-to-one pass-throughof all market rates. In this case, all spreads are unaffected, so the equilibrium volume is also unaffected by this change. The equilibrium in the extended model depends heavily on assumptions about shifts in the “habits” of households and financial intermediaries. Generally speaking, if portfolio habits in retail or wholesale central bank digital currencies come at the expense of another Fed liability or Treasury bond habit, then the equilibrium in the model is essentially unchanged relative to the baseline model.

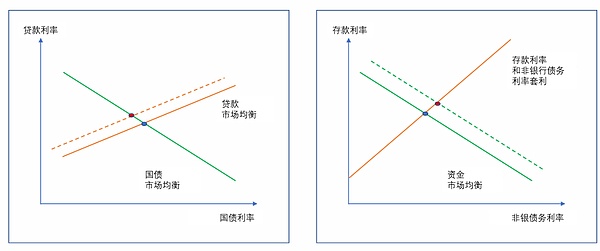

Specifically, an increase in retail central bank digital currency interest rates will put upward pressure on interest rates. As shown in Figure 4, the rise in R_CBDC interest rates shifts the loan market equilibrium curve upward, causing loan interest rates to rise and government bond interest rates to fall. This change also shifts the financing market equilibrium line outward, causing deposit rates and non-bank debt rates to rise as well. An increase in R_CBDC interest rates causes households to move from other assets to R_CBDC. The resulting reduction in funds available to deposits and non-bank debt market intermediaries led banks and non-bank institutions to reduce their asset size, with this decline occurring across all asset classes. There is a slight negative impact on total loans. On the Fed’s balance sheet, reserves, wholesale central bank digital currencies, other Fed liabilities and currency are all declining, while retail central bank digital currencies are increasing. Overall, the size of the Fed's balance sheet has increased.

Chart 4 The impact of interest rate hikes on retail central bank digital currencies

For the wholesale type, because the wholesale central bank digital currency (W_CBDC) is jointly held by banks and non-bank institutions. Therefore, the increase in W_CBDC interest rates directly affects bank and non-bank asset allocation. The impact of rising W_CBDC interest rates on interest rates is shown in Figure 5, which is similar to the parallel rise in reserve interest rates and other Fed liability rates in the benchmark model. As shown in the figure on the left, an increase in W_CBDC interest rates shifts the loan market equilibrium curve upward and to the left, and also pushes up the Treasury market equilibrium curve. The latter effect arises from the assumption that the W_CBDC rate becomes part of the “benchmark” rate on the foreign sector’s Treasury demand curve. The net effect is that both Treasury and loan rates rise. These increases lead to an increase in demand for funds from banks and non-banks – as shown by the outward shift of the funding market equilibrium line in the chart on the right: leading to higher interest rates on deposits and non-bank debt.

Chart 5 The impact of wholesale central bank digital currency interest rate hikes

< strong>Conclusions and Recommendations

The analysis of this article points out how the evolution of technology, regulation and financial structures may interact with the implementation and transmission of monetary policy. Several ways. In recent years, the Fed's introduction of fixed-rate assets in the form of interest-bearing reserves and fixed-rate overnight reverse repurchase agreements has created powerful new tools for policy implementation, and these tools are critical to maintaining high reserve levels in an ample reserve regime. The environment is the key to effectively controlling interest rates. So when the Federal Reserve (in the form of retail and wholesale central bank digital currencies) or professional financial intermediaries (in the form of stablecoins or deposits provided by narrow banks) introduce additional fixed-rate financial assets, they will interact with existing markets and institutions. Important aspects affecting policy implementation and transmission. These effects are most pronounced when new fixed-rate instruments serve as close substitutes for existing financial instruments.

The following is a partial screenshot of the article

decrypt

decrypt