Author: Carl Cervone,Gitcoin team member Source: mirror Translation: Shan Ouba, Golden Finance

Every funding ecosystem has core areas and important but secondary areas

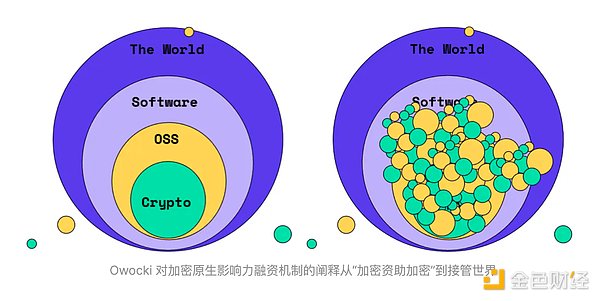

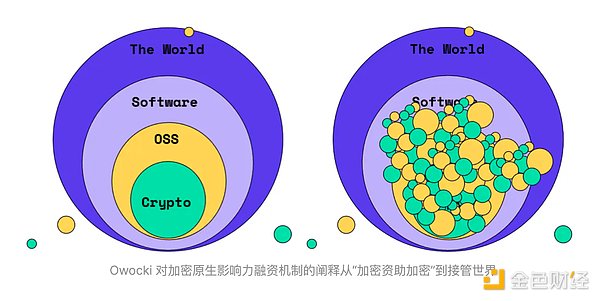

Gitcoin demonstrated the concept of nested scopes well in a 2021 blog post. The original article described a series of impact funding mechanisms, initially concentrated in the inner circle ("crypto"), spilling over to the next circle ("open source"), and eventually spreading across the globe.

That’s a nice way of saying it: start by solving problems at home and then expand outward.

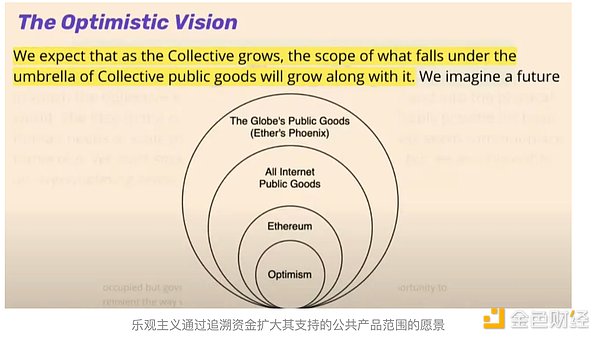

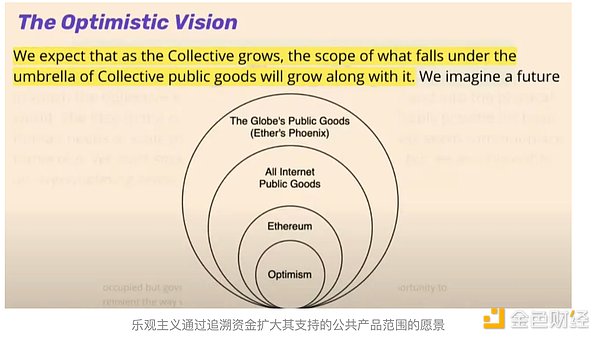

Optimism also uses a similar visualization to explain its vision for retroactive public goods funding.

Optimism belongs to Ethereum, Ethereum belongs to "all Internet public goods", and "all Internet public goods" belong to "global public goods". Every external domain is a superset of its internal domain.

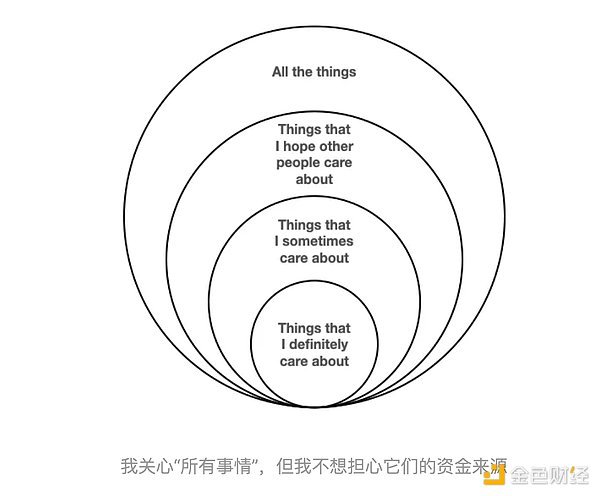

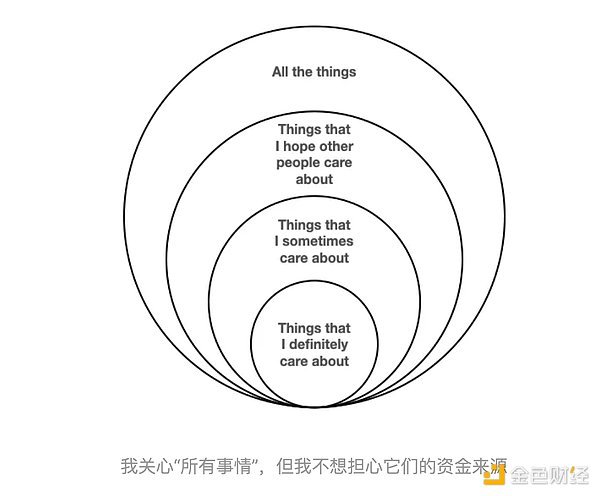

The following is a generalized version of my four-layer concentric circle meme.

Even though I personally may never spend time thinking about deep sea biodiversity or noise pollution in Kolkata, there are certainly a lot of people who care about these issues. Simply being aware of something tends to move it from the "everything" circle to the "things I want other people to care about" circle.

Most of us are not very good at assessing what is important outside of our "intimate circle"

We are generally able to reasonably assess the things we are in close contact with in our daily lives. This is our inner circle, and the things we absolutely care about.

In an organization, the inner circle might include your teammates, the projects you work closely on, the tools you use regularly, etc.

We can also evaluate some (but probably not all) things that are one level upstream or downstream from our everyday circle. These are the things we sometimes care about.

In the case of a software package, the upstream might be your dependencies, and the downstream might be the projects that depend on your package. In the case of an educational course, the upstream might include valuable lessons or resources that influence the course, and the downstream might include students who recommend the course to their friends.

Both software developers and educators can further care about the research upstream, and the institutions that manage that research, and so on. Now we are entering the realm of "care about everything."

However, most reasonable people no longer care deeply about anything at this point. Once you go beyond a single level of association, the situation becomes murky. These are the things we want other people to care about.

We risk using distance as an excuse not to fund these things and perpetuating the free-rider problem

While everything in our inner circle depends on good funding from the outer circle, it’s hard to justify investing more than our “fair share” (however it’s calculated) in things beyond a single layer of association.

There are several reasons for this:

First, it’s hard to categorize and sort across large scales. A category like “all internet public goods” is so broad that, with a little bit of twisting, almost anything could be considered to fall into that category and worthy of funding.

Second, it’s hard to incentivize stakeholders to care about funding things outside their inner circle because the impact is so diffuse. I’d rather fund an entire individual on a team I know than a small piece of work by an unknown person on a team I don’t know.

Finally, there are no direct consequences for not funding these things - assuming, of course, that others continue to fund them and don't give up.

Thus, we have the classic "free rider" problem.

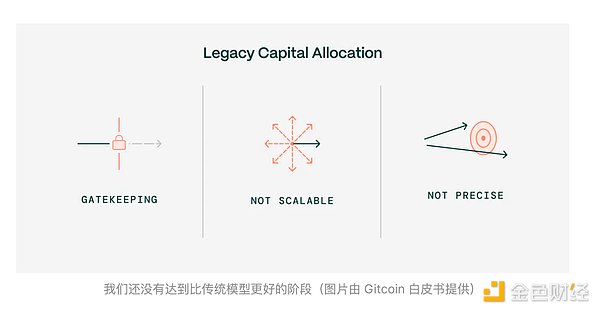

Beyond governments, which can print money, tax, and issue bonds to pay for long-term public goods projects, we as a society lack good mechanisms for funding things outside our immediate circle. Most of the money goes to things with shorter payback periods and more immediate impacts.

One way to solve this problem is to have people focus on funding things they are familiar with (i.e., things they can personally evaluate), and to create mechanisms to continually push some of the money out to the periphery.

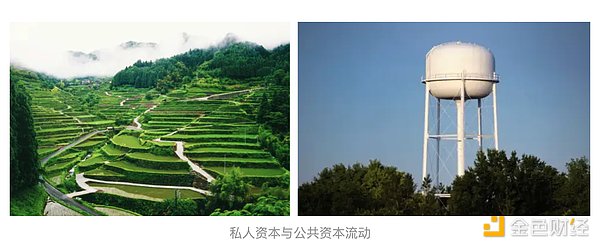

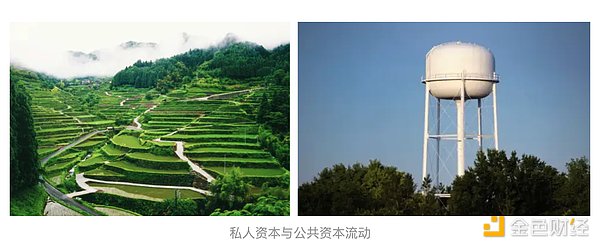

This, by the way, is how the flow of private capital works. We should try to emulate some of the characteristics of private capital.

Why the Venture Capital Model Works for Funding Short/Medium-Term No-Return Projects: Composability and Divisibility

The venture capital model for funding hard tech projects with payback periods of 5-10 years or more is a proven model - it's called venture capital (VC). Granted, the amount of money that goes to long-term projects in any given year is more influenced by interest rates than by ultimate value. But the model's effectiveness is proven by the trillions of dollars that VC has been able to attract and deploy over the past few decades.

The VC model works in large part because of the composability and divisibility of VC (and other sources of investment capital).

Composability: You can get VC, do an IPO, get a bank loan, issue bonds, raise money through more alternative mechanisms, etc. In fact, this is even expected behavior. All of these financing mechanisms are interoperable.

They work well together because there are clear rules about who owns what and how cash is distributed in different situations. In fact, most companies will utilize multiple financing vehicles during their life cycle.

Investment capital is also easily divisible. Many individuals will pay into the same pension fund. Many pension funds (and other investors) will be limited partners (LPs) in the same venture capital fund. Many venture capital funds invest in the same company. All of these divisive events occur above the company and its day-to-day operational concerns.

These characteristics allow private capital to flow efficiently through complex network graphs. If a venture-backed company has a liquidity event (IPO, acquisition, etc.), the proceeds will be efficiently distributed between the company and its venture capitalists, the venture capitalists and their limited partners, the pension funds and their retirees, and even from retirees to their children.

However, money flows differently in public goods networks. A network of public goods is less like having a large, intricate network of irrigation canals and more like having a few large watermarks (governments, major foundations, high net worth individuals, etc.).

To be clear, I am not advocating for venture capital funding for public goods per se. I am simply pointing out two important characteristics of private capital that public capital does not have.

How to get more funding for public goods from outside our inner circle

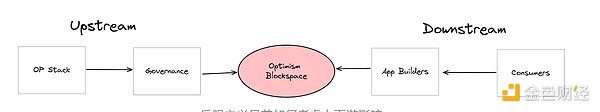

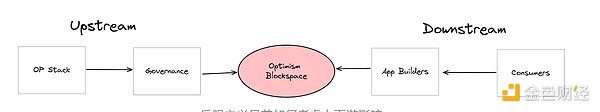

Optimism recently announced new initiatives for retroactive funding within its ecosystem.

In Optimism’s last round of retroactive funding, the scope of funding was very broad. But it is foreseeable that the scope of funding in the future will be narrower and more targeted to the closer upstream and downstream links in its value chain.

How Optimism currently considers upstream and downstream impacts

Understandably, there have been mixed responses to these changes. Many projects that were historically in the funding scope are now excluded.

The newly announced first round of funding will reserve 10 million tokens for "on-chain developers." In the third round of funding, the share of funds for on-chain developers is extremely low, accounting for only about 1.5 million of the total 30 million. So how will these projects make use of 2-5 times the previous retroactive funding?

One of the things they can do is to use some of the tokens for their own retroactive funding or grant rounds.

Specifically, if Optimism funds DeFi applications that drive network usage, then these applications can fund front-ends, portfolio trackers, etc. to achieve the impact these applications care about.

If Optimism funds the core dependencies of the OP stack, then these teams can fund their own dependencies, research contributions, etc.

What if projects took the retroactive funding they felt they were due, and then recycled the rest?

This is already happening in various forms. The Ethereum proof service now has a scholarship program for funding teams building on its protocol. Pokt just announced its own retroactive funding round, committing all the tokens it received from Optimism (and Arbitrum) to the round. Even Kiwi News, which ranked below the median among the recipients of the third round of funding, has implemented its own version of retroactive funding for community contributions.

Meanwhile, Degen Chain has pioneered an even crazier concept of allocating tokens to community members, which they must give away as “tips” to other community members.

All of these experiments route public goods funding from central pools (such as the OP or Degen Treasury) to the edges, expanding their reach.

The next step is to start making those commitments explicit and verifiable.

These attempts are happening in various forms. The Ethereum proof service now has a scholarship program for funding teams building on its protocol. Pokt just announced its own retroactive funding round, committing all the tokens it received from Optimism (and Arbitrum) to that round. Even Kiwi News, which ranked below the median among the recipients of the third round of funding, has implemented its own version of retroactive funding for community contributions.

Meanwhile, Degen Chain has pioneered an even crazier concept of allocating tokens to community members that they must give away as “tips” to other community members.

All of these experiments route public goods funding from central pools (such as the OP or Degen Treasury) to the edges, expanding their reach.

The next step is to make these commitments explicit and verifiable.

One way to do this is for projects to determine a floor value and a percentage above the floor that they are willing to commit to their pool. For example, maybe my floor value is 50 tokens and my percentage above the floor is 20%. If I receive 100 tokens total, then I will allocate 10 tokens (20% of my 50 tokens above the floor) to funding the edge portion of my network. If I only receive 40 tokens, then I keep all 40.

(By the way, my project did something similar in the last Optimism grant.)

In addition to pushing more funding to the margins, this also helps establish the cost base of public goods projects, playing a critical role. In the long run, the message for projects that consistently receive less funding than expected is that they have either mispriced their work or that the funding ecosystem they are in underestimates its value.

Projects with surplus will be evaluated in subsequent rounds not only on their own impact, but also on their broader impact as good allocators of funds. Projects that don’t want the burden of running their own grant programs should have the option to park their surplus somewhere else productive, like the Gitcoin matching pool, the protocol union, or even burn it!

In my opinion, these two values determined by projects before they receive funds should be kept private. If a project receives 100 tokens and gives away 10, no one else should know if their value is (50, 20%) or (90, 100%).

The final step is to connect these systems to each other.

The examples of EAS, Pokt, and Kiwi News are inspiring, but they all require launching new programs, then claiming/exchanging/transferring grant tokens to new wallets, and ultimately transferring funds to a new set of recipients.

Protocols like Drips, Allo, Superfluid, and Hypercerts provide the infrastructure for more composable grant flows - now we need to connect the pipes, like this pilot with Geo Web.

The work in this round is about creating public goods funding systems that actually work. Then, we start to scale them out.

Right now crypto is in the process of experimenting with the mechanisms for allocating large amounts of money and deciding what to fund. Public goods funding channels are far less sophisticated, composable, and battle-tested than DeFi.

For any technology to scale beyond the experimental stage, we need to solve two problems:

Measure that these approaches not only work, but are more effective than traditional public goods funding models (see this post for why this is an important problem people need to work on, and this post for some longitudinal analysis of Gitcoin’s impact).

Explicit commitments to how “profits” or surplus funds will flow to the outer circles.

In venture capital, there are always investors behind the investors — who may end up being your grandmother (or, more accurately, everyone’s grandmother). Each investor has incentives to allocate capital efficiently so that they can be entrusted with a larger share of capital in the future.

For public goods, there is always a set of closely related actors upstream and downstream of you, on whom your work depends. But there are currently no commitments to share surpluses back to these entities. Unless such commitments become the norm, it will be difficult to expand public goods funding beyond our intimate circles.

I don’t think it’s enough to just commit to “when we reach a certain scale, we’ll fund those things.” It’s too easy to move the goalposts. Instead, these commitments need to be established as quickly as possible and baked into funding mechanisms and grant programs as primitives.

I also don’t think it’s reasonable to expect a few whale foundations to fund everything. This is exactly the “water tower” model we currently see in traditional governments and big foundations.

But the sooner we make a clear commitment to fund our dependencies while they are still small, the more we can show that there is indeed a market for public goods, the more we can expand our addressable market (TAM), and change the incentive landscape.

Only then will we have something truly worth scaling that will gather its own momentum and create the “diversified, civilization-scale public goods funding infrastructure” we dream of.

Huang Bo

Huang Bo