By Charles Shen @inWeb3.com

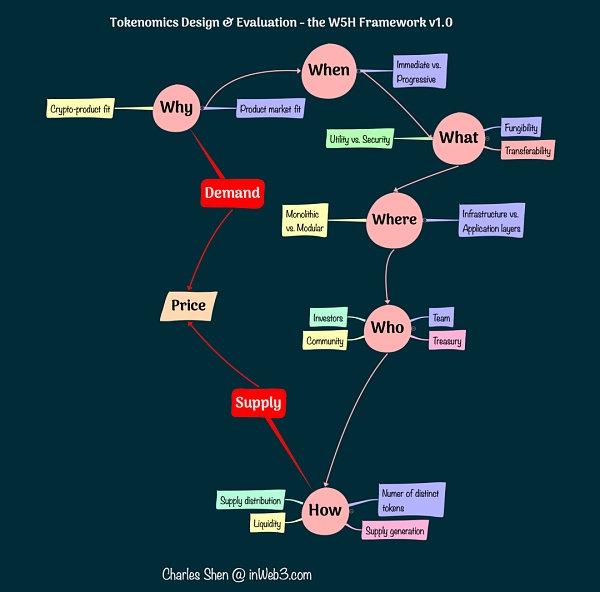

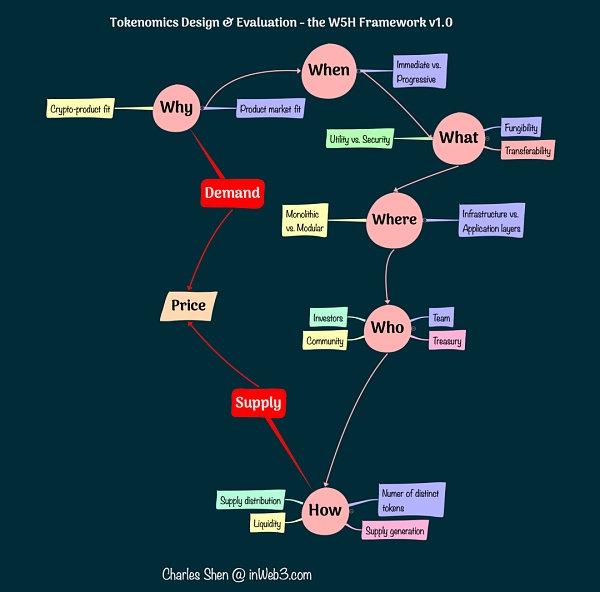

In previous parts of the Token Economics Basics series, we discussed the “Why, When, What, Where, Who, and How” in token design.

W5H Framework

While much of our discussion has been in the context of an initial token offering, the answers to these questions directly impact the ongoing supply and demand in the ecosystem, which is critical to the long-term sustainability of a token project. The dynamic balance of supply and demand at both the overall business level and the token level determines the price of goods, services, and tokens.These are the key components that complete our W5H framework and are the focus of this article.

W5H Framework (Supply and Demand)

As usual, we explore supply and demand dynamics at the business level and at the token level. At the business level, supply and demand for specific goods and services is actually part of the crypto-product-market fit problem discussed in “Why Tokens”. Therefore, we elaborate on the supply and demand mechanisms at the token level in more detail here.

Regulating Token Supply and Demand

Token Supply Regulation

Token supply can be regulated through the project’s governance mechanism. Recalling our previous discussion in the “How” section, token supply can be either pre-arranged or generated on demand. If the supply is pre-arranged, when circumstances change, some projects’ governance bodies choose to modify the original token issuance model to adjust future token supply. If token minting is demand-driven, the project’s governance can also take steps to adjust supply. For example, if a stablecoin is minted against collateral, lowering the required collateralization ratio will increase the supply of the stablecoin. However, this change comes with risks. A lower collateralization ratio increases uncertainty about the project’s overall financial health.

While supply adjustments can include increasing or decreasing supply, a more common problem for projects is an oversupply of tokens that cannot be absorbed by demand. Let’s explore the mechanisms for reducing token supply in more detail.

Temporary Supply Reductions - Locking and Vesting Periods

Locking tokens temporarily removes them from circulation and reduces selling pressure on tokens during the lockup period. Vesting periods mitigate sudden supply shocks by releasing tokens in phases. Projects can set incentives to encourage token holders to voluntarily lock their tokens. The more actual value the incentive brings to users, the more effective this mechanism is. For example, Curve Finance’s famous veCRV model locks CRV tokens for up to four years in exchange for governance rights and an ongoing share of protocol fees. Derivative protocols based on the veCRV mechanism, such as Convex, have even changed the lockup of CRV from temporary to permanent, further tightening the selling pressure on the token.

It is important to note that locking more tokens does not necessarily mean that the token will become more valuable.For example, if a token is used to exchange goods, and no one can access the token because all tokens are locked, then the exchange of goods cannot be carried out and the overall crypto economy will not exist.

Permanent Supply Reduction - Burning Tokens

Destroying existing tokens can permanently remove them from circulation. This method artificially introduces a deflationary force to counter inflationary pressure on the token and may increase the value of the token.Common token destruction mechanisms attempt to link the destruction process to token demand. One method is to destroy tokens when users use tokens to pay for protocol services. For example, ETH's EIP1559 scheme destroys part of the transaction fees. BNB also has a similar real-time partial transaction fee destruction mechanism. The Graph Protocol, which provides blockchain data query services, also destroys some of the fees it receives from query users and node service providers.

When a burn mechanism is designed to combat token inflation, it can be very challenging to design appropriate parameters to achieve a real-time balance of token supply and demand due to unpredictable factors in the economic system.A common approach is to periodically assess demand conditions to decide how much supply needs to be reduced, and then buy back and burn those tokens. For example, the quarterly automatic burn mechanism for BNB tokens determines the burn amount through the price of BNB tokens and the supply and demand dynamics, which means that if the price of BNB falls, more tokens will be burned.

Slowing and reducing future token supply

Supply slowing and supply reduction measures can also be taken for future tokens that have not yet been released.

Tokens scheduled for future releases often adopt a more gradual release model rather than a step-function-based inflation jump. For example, the release of the CVX token scheduled in advance by the Convex protocol is a good example of a smooth minting curve with a reduced inflation rate. Lockup and vesting periods are often enforced for tokens that are intended for specific participants, especially those that receive investment or rewards at low or no cost. For example, teams and venture capital firms often receive allocated tokens after lockup periods of less than a year to several years. These tokens are typically vested gradually over 1 to 3 years. Similar lockup and vesting periods can also be applied to token rewards earned through yield farming, such as in the DeFi Kingdom game.

We have also seen some projects explicitly cut issuance by adjusting future issuance plans. For example, the Sushi token initially set an unlimited inflation plan, but later its governance body deemed this plan too aggressive and approved a hard cap of 250 million. The Cosmos 2.0 white paper released in September 2022 proposed changing the long-term issuance plan of ATOM tokens from exponential expansion to a more constrained linear plan, but this would also require a significant increase in token issuance in the short term, so it was rejected along with other amendments.

Regulating Token Demand

Handling supply and demand dynamics is not limited to the supply side, and demand can also be stimulated or suppressed based on changes in supply caused by external factors.MakerDAO's DAI Savings Rate mechanism is a good example. In the base scenario of MakerDAO's DAI stablecoin, people mint DAI with ETH tokens as collateral, thereby increasing the supply of DAI. In a crypto bull market, people are more inclined to use ETH leverage to mint DAI, resulting in an increase in DAI supply and relatively weak demand. At this time, the protocol can reward people who hold DAI by increasing the DAI Savings Rate, thereby increasing the demand for DAI and making the supply and demand relationship more balanced. In a bear market, people prefer the stability of holding DAI, because people generally do not use ETH leverage to mint DAI, resulting in a stronger demand for DAI than supply. At this time, the protocol can reduce the DAI Savings Rate to dissuade people from holding DAI and suppress its demand.

Token Supply and Demand Analysis

There are three common questions we can ask when analyzing the supply and demand dynamics of tokens and the token prices they affect. Two of them will be discussed in this section, and the third question about token value capture will be discussed in the next part of this series. We have also selected two representative projects from the recent crypto market cycle to illustrate the application of these questions.

What kind of value creation drives the demand for tokens, and is this demand sustainable?

In answering this question, we will ignore the supply side for now.The system should have a solid foundation that can support continuous and growing demand for tokens.We can review the answer to the question "Why a token" and dive deeper into the business model of the token project and its value creation process. Are there meaningful services and products that generate revenue? Where does the revenue come from? Is the revenue sustainable? How do the revenue and costs compare?

If a system is not yet financially sustainable, but provides meaningful services, it may still succeed. Just like a technology company can lose money during its growth period but still succeed. These projects can obtain external funding (mainly from venture capital firms) to help them get through the early stages. Of course, such projects are not guaranteed to succeed, and many inevitably fail.

If a system appears to be profitable, but relies primarily on a constant influx of new user funds to maintain its business model, then one should be wary of its potential "Ponzi economy".

How will the token supply change, and can demand match?

If a crypto project passes the basic demand-driven test at a given token supply, we still need to check whether the changing token demand and supply can achieve a healthy balance.

If the supply decreases, it should help push prices up in the short term if demand is similar. But if the supply decreases too much, it may suppress demand and hurt the overall economy. Therefore, many token economies are designed to have a moderate supply inflation. This inflationary supply can be on a predetermined schedule or released on demand. Let's look at what might happen with the new token supply:

People might sell them on the market and cash out; this is the least desirable scenario because it indicates that supply has increased while demand has decreased, which drives down prices.

Sponsored Business Content

People might hold tokens for the long term. This behavior is desirable because it indicates increased demand and temporarily removes new supply from circulation, reducing selling pressure.

People may use the new tokens to pay for services that burn the tokens. This outcome also represents demand for the token and is highly desirable because it essentially eliminates additional supply and minimizes dilution from new supply.

Other user behaviors may fall somewhere in between the above, resulting in various degrees of demand impact.

If user demand is consistently unable to match supply, the economy may fall into hyperinflation mode, causing token prices to collapse.

Case Study 1: OlympusDAO and OHM

OlympusDAO is a representative project of DeFi 2.0. It aims to create a decentralized, censorship-resistant reserve currency for the emerging Web3 ecosystem. The goals of the OHM token are to maintain purchasing power, maintain deep liquidity, and serve as a unit of account and store of value. But unlike crypto stablecoin projects, the OHM token is not pegged to the US dollar, but is backed by assets such as the decentralized stablecoin DAI. This change from “pegged” to “backed” is significant, meaning that OHM has a free-floating value, but its intrinsic value is determined by the asset it backs.

What is the main value that attracts users to buy OHM tokens?

When OHM was launched in early 2021, its main attraction was not its status as a currency, as it was not yet widely adopted. Instead, it offered a high six-digit passive yield (APY) for staking OHM. Even in mid-2022, the APY remains in the mid-three-digit range. This high yield, along with the (3,3) meme, was the main reason people bought and staked OHM at the time.

Where does OHM's yield come from, and is it sustainable?

Diving deeper into the protocol reveals that the early APY came primarily from the protocol selling OHM to buyers willing to pay far more than the intrinsic value of one DAI. But why are people willing to pay a higher price, peaking at $1,415 in April 2021, despite an intrinsic value of about $1? Some users may believe that the future growth of the project, including the large treasury assets controlled by the protocol through the bonding mechanism, is worth paying the premium. Others may have FOMO (fear of missing out) because of the (3,3) meme. If everyone acts in concert and only buys and never sells, the price will continue to rise. If the price continues to rise, early entry leads to better prices and higher distribution of protocol value. The only problem is that for the price to continue to rise, an infinite number of new buyers need to enter the system. When the influx of new buyers stops, the system goes from Tokenomics to Ponzinomics. Jordi Alexander from Selini Capital has more insights on this. In summary: Overall, the Olympus Protocol has some impressive designs, an ambitious goal, and a once extremely popular meme. Unfortunately, its model lacks a solid foundation and cannot be sustained. In hindsight, it is not surprising that the OHM price has fallen by more than 99% from its all-time high.

Nevertheless, the Olympus project also brought some influential innovations, especially the concept of protocol-owned liquidity, which is considered a key feature of DeFi 2.0. As of early 2023, the protocol still has nearly $250 million in treasury assets.

Case Study 2: Axie Infinity

Axie Infinity is an NFT-based blockchain game. Players fight, collect and trade NFT digital pets called Axies in the game. It is the symbol of the "play to earn" game.

What is the main value that attracts users to participate in the Axie Infinity game and its token?

Many players are attracted to Axie Infinity because they can earn income. In May 2021, a survey conducted by game developers on Twitter showed that 48% of nearly 1,000 respondents participated in the game for "economic" reasons, while only 15% participated for gameplay. This means that most participants are looking for work, not for the game. Where does the game's revenue come from, and is it sustainable? If people are playing the game to make money, where does the money come from? Unfortunately, the early Axie Infinity economy did not generate self-sustaining revenue. It required players to pay an upfront fee to purchase the game's NFT to start playing. At its peak, the price of an entry NFT ranged from a few hundred dollars to over $1,000. New users continued to pay fees to join the game, which supported the token price at a level that enabled existing players to cash out and earn a significant income. However, it is unrealistic to expect an unlimited number of new users to join the system at increasingly higher prices. When new user growth slows, the token price drops, and existing "working" players cannot earn enough income to make ends meet. They may leave the game, leading to a vicious cycle. In short, the demand side fundamentals of the game fail the sustainability test.

How will the token supply change?

Axie Infinity has been praised for providing an opportunity for low-income communities to earn a living through a “play to earn” model. This is indeed a commendable cause. A guild-based scholarship mechanism was also created to help users who could not afford the game’s entry NFTs to join the game. The idea was to let them borrow the necessary NFTs to start the game, after which they could repay the loan and keep the remaining earnings. This mechanism worked and was effective in attracting a large number of users to the game. It is estimated that 60%-65% of Axies owners are scholarship holders.

However, many new users entering the system also means that the token supply accelerates, for example, people win more SLP tokens in the game. This situation exacerbates the existing inflationary pressure caused by bots, further driving the minting of more tokens.

Will the token demand match the supply changes?

On the demand side, users can sell the earned SLP and cash out. These SLPs re-enter circulation, creating inflation. Users can also use these SLPs to breed Axies, which will burn and reduce SLP tokens. Therefore, the outcome will depend on the relative speed of SLP inflation and deflation. NAAVIK's analysis of SLP minting and burning shows that since August 2021, SLP has been minted faster than it has been burned, and the minting/burning ratio continues to accelerate. Clearly, deflationary forces are not strong enough to offset the increased supply. If we recall, most scholarship holders and low-income players treat gaming as a job, earning cash income by winning SLP tokens and selling them. These players primarily play through inflationary pathways, not deflationary pathways.

If we look at the price of SLP tokens and their market cap, August 2021 marks a period of rapid decline in the price of SLP tokens from close to $0.34 to between $0.05 and $0.10. This pattern suggests that the game is experiencing severe inflation issues.

Balancing a game economy is never an easy task. Solving the severe inflation of in-game SLP requires designers to reduce sources of token inflation and/or add deflationary means. But these decisions often present dilemmas. Reducing the number of SLP token rewards would also change player incentives, potentially affecting their engagement. On the other hand, limiting the number of Axies could be a way to encourage breeding and lead to more SLP burns. But it could also lead to higher Axies prices, further increasing the barrier to entry for new players.

To their credit, the team has publicly acknowledged these issues and has been working on improvements in various directions. They addressed the severe inflation issue by making it more difficult to obtain SLP tokens and further controlling the number of Axies. As for the fundamental question of actual revenue sources, they list several options on the Axie Economy and Long-term Sustainability page. They also released a free trial of the game as part of these efforts, potentially attracting more people from the wider player community and generating revenue through in-game items.

Conclusion

This article builds on the previous discussion of “Why, When, What, Where, Who and How” in token design and further explores the dynamic balance of supply and demand to complete the W5H cycle. Since the supply and demand dynamics at the business level have been covered in the previous “Why Tokens” discussion, this article focuses on various methods to regulate supply and demand at the token level. Through two representative crypto project cases, we analyzed in detail two key questions covering the business and token levels that help evaluate the supply and demand relationship of a specific crypto project.

An important issue that we have not explored in depth is the connection between these two levels. Specifically, how the value created at the business level accumulates to the token level. This is a key part of token economics design and affects the valuation and pricing of tokens. This will be the topic of discussion in the next part of the series on token economics basics.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance